We celebrate the 150th anniversary of the famed Chisholm Trail by getting to know its historical namesake, Jesse Chisholm, a trader who blazed a route from Wichita, Kansas, across the Indian Territory to the Red River — but never drove cattle himself.

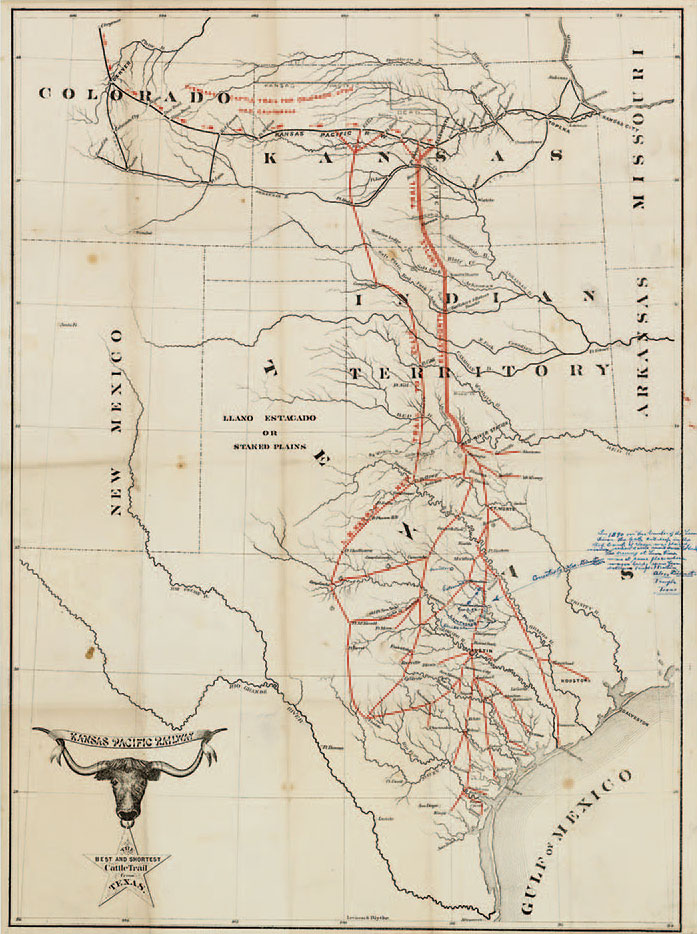

The Chisholm Trail, which reaches its 150th anniversary this year, is the most famous cow path in world history. Between 1867 and 1884, an estimated 5 million head of cattle, and a million mustangs, were driven up the trail from Texas to railheads in Kansas. It was the largest migration of livestock ever recorded, and it produced a new figure in American history: the tough, proud, footloose Texas cowboy. Long after its demise, the Chisholm Trail was celebrated in at least 27 Hollywood films; the best is still probably Red River (1948) with John Wayne and Montgomery Clift.

Less well-known is the man for whom the trail was named. Jesse Chisholm was not an early Texas cattleman, as people often assume. Nor did he drive a single head of beef up his namesake trail. Half-Cherokee and half-Scottish, Chisholm was a trader, explorer, scout, and diplomat who brokered many important peace negotiations between whites and Indians in Texas and Oklahoma. His biographer, Stan Hoig, sums him up as an “ambassador of the Plains.”

Unfortunately, Chisholm left behind no journal, diary, or personal documents that we know about. A trunk full of his papers is said to have burned up in a house fire. Only one unrepresentative photograph of him exists, taken late in his career when he was in poor health. Chisholm remains a mysterious, elusive figure, with an almost uncanny ability to be present at key events in frontier history.

Chisholm was a brilliant linguist who spoke 14 tribal dialects, in addition to English and Spanish. This, and his sterling reputation for honesty, wisdom, and integrity, made him invaluable at treaty negotiations and peace councils. To survive for as long as he did, so far from civilization, he must have been an expert at reading sign, finding game and water, dealing with dangerous weather, and avoiding ambushes. And like Joseph Walker, the mountain man turned trader who never lost a man under his command, Chisholm understood that diplomacy, not firepower, was the real key to survival on the frontier.

He was probably the only man with white blood who could ride into a camp full of angry, vengeful Comanches painted for war and ride out again with his scalp attached and a string of ponies into the bargain. Ten Bears, the principal chief of the Yamparika Comanches, was a close personal friend. Chisholm was also on friendly terms with Buffalo Hump, who led a thousand rampaging Comanches on the great raid of 1840, with Satanta, the last great Kiowa war chief, and Sam Houston, the founder of Texas. Circumstances often made it difficult, but throughout his career, Chisholm tried to be a faithful friend to both the white man and the Indian and refused to pick sides.

He was born in Tennessee, in 1805 or 1806, to a Scottish father and his Cherokee wife. At the age of 5 or 6, with the Scotsman gone, Jesse’s mother took him away to live with the Western Cherokees on the Arkansas River in present-day Arkansas. He lived a Cherokee boyhood of hunting, trapping, woodcraft, dances, and clan rituals, at a time of ever-present danger. The Western Cherokees were engaged in ferocious tribal warfare with the Osages. At 20, Chisholm was living in the polyglot, multiethnic community at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, a remote outpost. Like so many young men who grew up on the frontier, he yearned for adventure in the great unknown spaces farther west.

In 1826, he joined a gold-hunting expedition, following the Arkansas River all the way up into Kansas. Returning empty-handed to Fort Gibson, he started buying corn from Cherokee farmers and selling it to the military. Soon he was bartering coffee, sugar, cooking pots, cloth, guns, knives, and other manufactured goods with several tribes in Oklahoma, and bringing back furs, moccasins, horses, and mules. It was profitable, interesting work but risky. War parties roamed the landscape like pirates on the ocean.

His first big adventure came in the summer of 1834, when he rode as a scout for the Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition. This was the first attempt by the U.S. government to make friendly contact with the Southern Plains tribes. The 500-strong party included the First Regiment of U.S. Dragoons; 30 Cherokee, Osage, Delaware, and Seneca scouts; Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy; and the traveling artist George Catlin, who recorded the expedition in sketches, paintings, and journal entries.

The boundary between the eastern farming tribes and the western horse nomads was a densely wooded strip of low trees and brush known as the Cross Timbers, running down through Oklahoma into northeast and central Texas. After working through it for three days, the expedition broke through onto a vast prairie with enormous herds of buffalo, wild horses in abundance, and occasional glimpses of mounted Indians in the far distance. Already the Dragoons were wracked with fever and disease, probably cholera.

They soon encountered Comanches, who were friendly and hospitable and invited the soldiers to camp near a large village. Hundreds of tepees were surrounded by some 3,000 grazing horses and mules. The Dragoons established a sick camp nearby and another outside a Wichita village of grass huts. Gift-giving and parley sessions began.

In diplomatic terms, the expedition was a success. With Jesse Chisholm translating via the Caddo language, peaceful relations were established with the Comanches, Wichitas, and Kiowas. No one at the time could have known how fragile this peace would prove. In terms of human suffering, the expedition was nightmarish. A third of the men died of disease or thirst as they toiled across the parched plains in the furnace of summer. Gen. Henry Leavenworth perished along the way. Col. Henry Dodge, who barely survived, thought that no campaign in America had ever “operated more severely on men and horses.” For Jesse Chisholm, it was an initiation, and a turning point. His future lay out there on the plains.

In 1836, having turned 30, Chisholm married 15-year-old Eliza Edwards, the half-Creek daughter of a trader named James Edwards. He based himself at Edwards’ remote trading post on the Canadian River in Oklahoma, a place that Hoig describes as “a port on the coast of an unexplored prairie-ocean that challenged the courage of those who dared venture onto it.”

Chisholm loaded up his wagons with trade goods and headed out onto those prairies, looking for Indians willing to barter for horses, mules, buffalo robes, and other furs. He was courageous and commanded respect, but his real skill was avoiding and defusing confrontation with militant scalp-hunting warriors. He became the first outsider to gain permanent access to the Comanche and Kiowa lodges, and this enabled him to free many white and Mexican captives over the years.

As a husband, however, he was a dismal failure. Eliza said that Jesse would visit her once a year, stay for a week or two, and then disappear again for another year. Chisholm was one of those restless frontiersmen who preferred the privations of the trail to the confinements of home. In 1839, he took up with a party of frontiersmen and Delawares and blazed a new trail to California through West Texas. A few years later, he rode down into Mexico to hunt for the missing Cherokee intellectual Sequoyah. One senses that any excuse for an adventure would do.

In 1843, Sam Houston, now the reelected president of the new Republic of Texas, hired Chisholm and a group of Delaware scouts to scour the North Texas plains and bring in the Comanches and other tribes for a grand peace council. Chisholm had known Houston during his hard-drinking years as a trader among the Cherokees, and Houston’s Cherokee wife, Diana, was likely related to Chisholm’s family.

The leading Comanche chiefs agreed to meet with Houston the following year. They talked for two days, with Chisholm translating for Sam Houston and Buffalo Hump, and finally signed a compromise pact. Buffalo Hump agreed to stop stealing horses and taking white captives, but he refused Houston’s proposition of a dividing line between Comanche and Texan territory. The resulting peace didn’t last long. The conflicts between white Texans and Comanches were too deep to be solved by negotiation.

In 1846, Chisholm accompanied a delegation of 41 Plains chiefs to Washington, D.C., to meet with their “Great Father,” President James K. Polk. The idea was to show the Indians the overwhelming power and numbers of the whites and the futility of trying to resist them. The delegation went by steamboat down the Red River to New Orleans, and then up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Disembarking at Wheeling, West Virginia, they continued by stagecoach to the nation’s capital, where their buckskins, paint, and feathers were gawked at and ridiculed.

They toured the sights and were suitably impressed, but soon became homesick. With silver medals of friendship from the president and an appropriation of $50,000 secured from Congress, the delegation returned with relief to the wide-open plains. Chisholm now moved his operations north of the Red River to Oklahoma and Kansas.

We don’t know when Eliza died, but it was probably in the mid-1840s. She gave him a son named William, and possibly more children. In 1847, Chisholm married another half-Creek woman, Sahkahkee McQueen, and set up a home on the Canadian River near present-day Asher, Oklahoma. A daughter named Jennie was born, and more children would follow. The household also included two former captive children that Chisholm had freed from the Comanches and adopted as his own.

For the next decade, he continued to broker peace treaties for the U.S. government, free captives, mediate between the eastern and western tribes in Oklahoma, and conduct his trading business. As white encroachment diminished the Comanche and Kiowa territory in Texas and America expanded into Kansas, western Oklahoma became a refuge for the Plains tribes, and Chisholm appears to have been the only trader operating there.

After the chaos of the Civil War, when some Oklahoma tribes fought for the Confederacy and others for the Union, Chisholm helped to bring order to Indian Territory and secure protection and resources from the government. The origins of Chisholm’s famous trail date to this period, but we don’t know exactly when. The trader James R. Mead, who knew Chisholm well, stated that in 1865, or perhaps 1866, Chisholm purchased trade goods from him, loaded his wagons, and blazed a direct trail from his ranch on the Arkansas River in Kansas to Council Grove on the Canadian River in Oklahoma.

It is only this northern section of the trail that Chisholm established. The longer southern portion was blazed by Texas cattle drovers, and the whole thing soon became known as the Chisholm Trail. Longhorn cattle had multiplied exponentially on the Texas plains during the war. The North was crying out for beef. The Chisholm Trail, in the words of Texas literary giant J. Frank Dobie, who would be instrumental in saving the Texas Longhorn from extinction, enabled “the greatest, the most extraordinary, the most stupendous, the most fantastic and fabulous migration of animals controlled by man that the world has even known or can ever know.”

For Jesse Chisholm, the end of the trail came in April 1868. Following the famous Medicine Lodge Treaty, where he had fallen ill, he had been trading on the North Canadian River with Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos. His food supplies were low, and he longed for bear tallow. Hearing this, an Indian woman brought him some in a small brass kettle. The metal pot had contaminated the grease. Chisholm ate heartily and died soon afterward. He was in his early 60s.

He was buried across the North Canadian River from a red butte known to the Indians as Little Mountain. His old friend Ten Bears sang the death song at the grave and placed the gold peace medal that Abraham Lincoln had given him on Chisholm’s chest. They wrapped him in a blanket and a buffalo hide and lowered him down. Ten Bears mounted his cream-colored pony and rode off weeping. At Council Grove, Chisholm’s trader friends toasted him with Kentucky whiskey and fired their buffalo guns into the sky.

Just a few days before his death, Chisholm had talked to his friend James Mead, who quoted him in his eulogy for The Wichita Eagle. “I know little about the Bible and churches,” Chisholm said, “but ... I have never wronged anyone in my life. I have been a peacemaker among my brethren. No man ever went from my camp hungry or naked, and I am ready and willing to go to the home of the Great Spirit, just as I am, whenever he calls for me.”

For information on events and attractions related to the Chisholm Trail’s 150th anniversary — along with trail history and maps of markers, monuments, and ruts — visit the official website.

From the April 2017 issue.