Cree photographer Richard Throssel created an important and intimate photographic record of life on the Crow reservation in the early 1900s.

Looking out the east side window of the newly renovated historic Stapleton Gallery in downtown Billings, Montana, you can get a glimpse of what used to be the home and business of Richard Throssel. A century after he was active in Montana, the gallery revisited his legacy in Crow Now: A Visual Survey 1904 – 2016, an exhibition dedicated to the people of the Crow Nation and to the life’s work of perhaps one of the most important and prolific Indian photographers of the early 1900s.

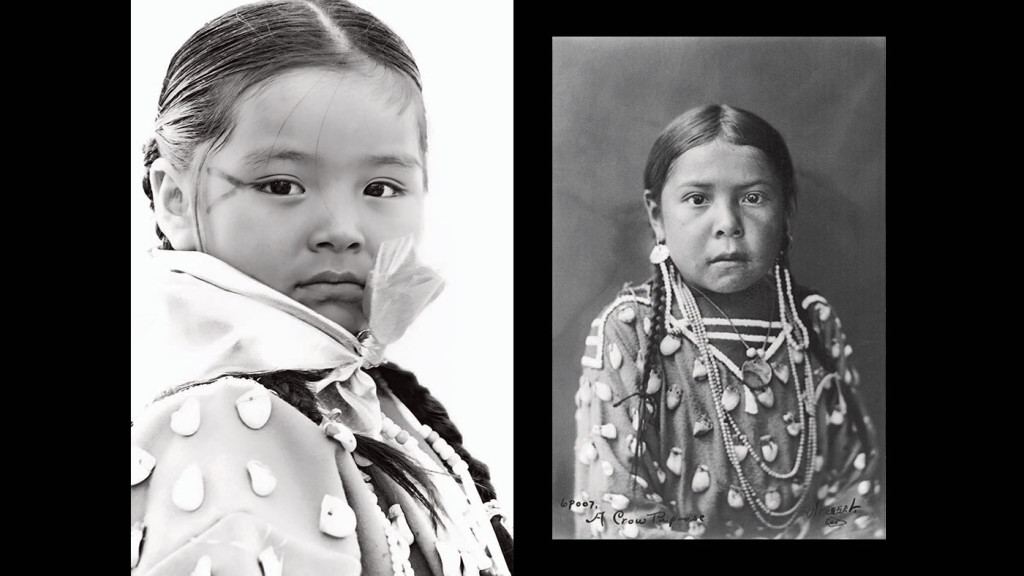

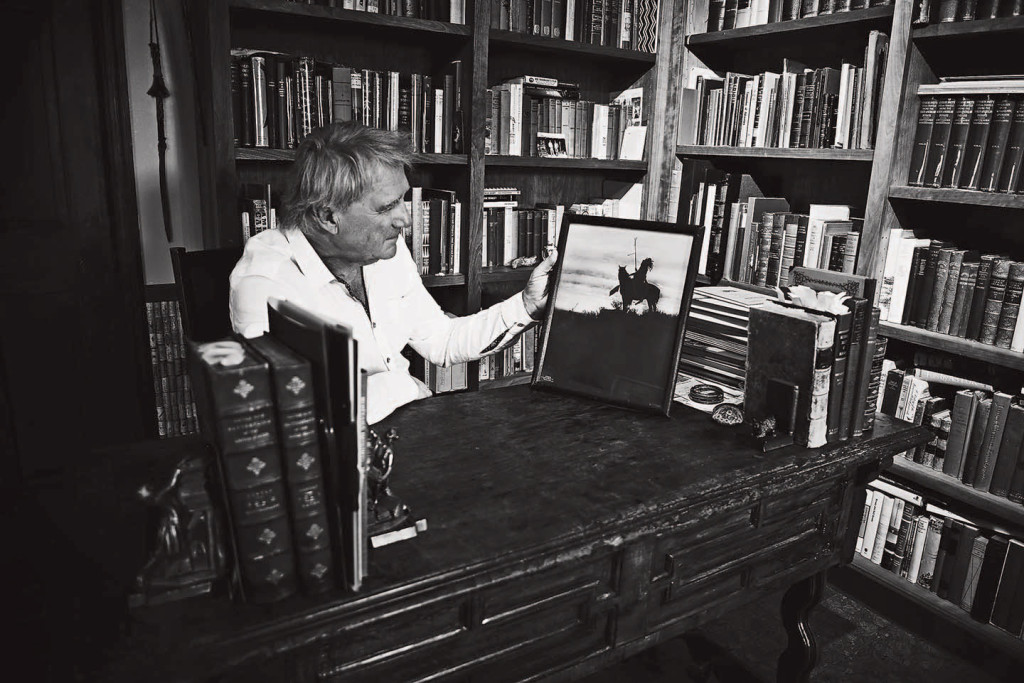

Kevin Red Star, Ben Pease, Judd Thompson, and I were invited by gallery owner Jeremiah Young to participate in the exhibition. Each individual artist was asked to select original Throssel images to draw inspiration from to create a new modern take on works from 100 years ago. We met in early August at the home of historian Thomas Minckler, who has one of the largest privately owned collections of Throssel photographic originals, and pored over the images, immersed in the everyday life of the Crow during the first decade of the 20th century.

Throssel had met and learned from Edward S. Curtis, and while some of Throssel’s work sometimes showed resemblances in romanticized posed portraits, his photographs took another tack. Instead of formal portraits of Native Americans in traditional clothing, here were people in their true context, captured candidly, living without artifice, very much alive and not vanishing. Some of the corners of the photos curled down slightly, the tones and age spots reminding me that the people in the photos had long since died. But the faces, the lifeways, the emotion that emanated from these timeless images proved that they had really lived.

It also struck me that Throssel’s photographs were similar in content to my own work among the Crow — almost eerily so. Even specific faces seemed vaguely familiar. I realized in that moment that though time had progressed, families, traditions, and landscapes for the most part had not changed.

Throssel would have been witness to abject poverty, isolation, disease, and forced assimilation. Yet in spite of all the adversity surrounding Crow culture, he focused on beauty and strengths rather than his era’s negative stereotypes of indigenous people. He managed to portray his subjects with honor and dignity — images that their children’s great-grandchildren would be able to look upon with pride and great understanding of their ancestors.

Up until a few years ago, I had no idea who Richard Throssel was. When I discovered his photographs, the parallels between his work and my own fascinated me. Both of us, adopted by the Crow, had an intimate access that nonmembers couldn’t have. Wanting to learn more about him, I went to the archives at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center in Laramie. There, I spent hours scrolling through images I had never been exposed to, and reading correspondence explaining Throssel’s processes and descriptions of the work he was doing.

His early biography only hinted at the important work he would eventually do. Richard Albert Throssel was born one-quarter Native American — variously described as Canadian Cree, Red River Metis, and Wasco, he self-identified early in life as Wasco-Cree — and three-quarters Scottish and English heritage in Marengo, Washington, on September 18, 1882, the same year his family had gone west to pick hops. He attended school through the fifth grade and thereafter went only every other year so that he could work in the fields with his family. In high school, he began taking lessons in drawing and painting; in college, he took correspondence classes in art.

In 1902 he relocated to Montana due to an illness that required him to be in a much drier climate. There, he joined his brother, Harry, and the two began working as clerks for the Indian Agency on the Crow Reservation. “Due to his indigenous background and progressive inclinations, Agent Samuel Reynolds held Throssel up as model of progress to Crows during the early reservation period,” writes John Ille, archivist at Little Bighorn College, a Native American tribal college on the Crow Indian Reservation in Crow Agency. “Throssel gained the goodwill of many Crows and took hundreds of photographs of Crows during and after his tenure at the Agency,” Ille writes, so much so that in 1906, a council of Crow elders would adopt the brothers into the Crow Tribe.

He had learned photography shortly after arriving on the reservation. When Edward S. Curtis visited the reservation in 1904, in the process of compiling his 20-volume work The North American Indian, Throssel studied his technique and aesthetic, improving his approach to composition and lighting. “It was a revelation, indeed,” Throssel wrote. “This was really the starting point in my work.”

It was a significant time for another reason: He married Florence Pifer, a laundress and teacher at the agency, with whom he would have two daughters, Vera and Alberta. Florence was not an adopted member of the Crow Tribe, but she was fluent in the Crow language, and she taught Throssel to speak the language, which helped him not only in his agency work but also in his photography.

Throssel would charge a dollar for a portrait, and Native Americans would come from miles around to have their pictures taken. He also tried his hand at painting, an undertaking enhanced when Taos Society of Artists founding member Joseph Henry Sharp arrived on the reservation and gave Throssel instruction in technique. Though Throssel wouldn’t pursue painting as seriously as photography, knowledge of principles of design and composition picked up from Sharp evolved his photographic eye.

But it was the acceptance and access that came with adoption into the tribe that really furthered his work. Christened Ashua Eshquon Dupaz, or Kills Inside the Lodge (or Camp), by Bull Don’t Fall Down to commemorate a successful attack on a Sioux camp in reprisal for killing Crow women, Throssel gained admittance to secret ceremonies and dances and could easily observe scenes of everyday life that otherwise would have been impossible to capture. The fact that he was allowed to document such events speaks to the trust and relationships he was able to cultivate. One of these close friendships was with the famed Chief Plenty Coups, whom Throssel would photograph several times.

Throssel credited his own heritage: “To my French parentage, I owe my imagination and love for the beautiful artistic,” he told the Billings Daily Gazette. “To my Indian blood I must acknowledge that insight into Indian nature and Indian life that marks all my work among them with the camera.”

His images of the Crow and Northern Cheyenne were both stylized and romantic, like those of his mentor Curtis. But he took a different approach at times capturing candid moments and action shots. This separated his work from Curtis’. Throssel’s had a warmth and sensitivity to it. Not all images were perfect, but they depicted the true nature of reservation life. Nor were they all pleasant, as when he was hired in 1909 to document patients with tuberculosis for a scientific study (he used his photographs as a tool to teach hygiene). But they were authentic. The unique quality in his images perhaps came from the close-knit relationships and bonds he had formed with the tribal members. Living and interacting with these people on a daily basis would have created a comfortable atmosphere while posing and taking their portraits. The rolling hills and vast plains (east of the Bighorn Mountains on the western edge of the Powder River Basin of the northern Great Plains) would have provided him with the perfect backdrop.

His skill and access also gave him credibility as a documentarian. “By 1908 Throssel’s proficiency behind the camera and his friendship with many Crows allowed him to contribute photographs to the Wannamaker-Dixon expedition,” relates Throssel scholar Peggy Albright, author of Crow Indian Photographer: The Work of Richard Throssel (University of New Mexico Press, 1997), who donated her research on him to Little Bighorn College.

In 1909, he quit his position as clerk in order to be a field photographer for the Indian Service, which he did for about two years. His adoption formally approved by the government in 1908, Throssel and his wife were allotted land near Wyola, Montana, in Big Horn County in 1910.

He left the reservation in 1911 and struck out as a full-time photographer in Billings, where he set up shop downtown on the corner of North Broadway and First Avenue North. There, he established the Throssel Photocraft Company, just down the street from what is now the Stapleton Gallery. He would return to the reservation frequently to continue his documentary-style work. Derived from these works were his most famous set of images, “The Western Classics From the Land of the Indian,” a series of 39 photographs that romanticized the life of the Crow Indian.

After establishing his commercial photo studio, he sold prints from early negatives through catalogs but was never quite able to satisfy his desire, as Albright quotes him, to “get back to the work where I left off and complete the set of pictures I have started.” Nonetheless, his studio was successful. (But his work largely went unnoticed outside of the region until the publication of Albright’s Crow Indian Photographer in 1997.)

All the while, Throssel worked tirelessly to improve conditions on the reservation. He wrote several newspaper articles and public letters petitioning for protection of Native American interests, including health conditions, rescission of tribal land, improvement of roads and highways, and updating laws that would allow American Indians to control their own finances. “Give the Indian a White Man’s chance if you wish to make him his equal,” Throssel wrote in an August 5, 1917, article, “Crow Indians to Petition Great White Father for Emancipation,” in the Billings Daily Gazette.

His profound interest in the welfare of Native Americans led him into politics. In 1916, Throssel had become a citizen and in 1924 ran for and won a seat in the Montana legislature, where he served two terms as a Republican from Yellowstone County.

Though he no longer had time for fieldwork, he did keep his studio open until his death of a heart ailment on June 10, 1933, at the age of 50. He died having achieved much. In addition to his photography of the Crow and his civic service, he also raised a family, successfully ran his family apartments, worked for the Gazette as a photographer and photo engraver, and even served as the first president of the Yellowstone Rifle Club.

Carefully going through his photographs, I considered how his work and life had inspired me and what I might do in response for the exhibition. I decided my first step would be to go pay my respects at Throssel’s grave. Journeying a quick 3 miles across town from the gallery to Mountview Cemetery, I found him in section five, where Throssel shares a plot and a headstone with his wife, Florence.

Other than their names and dates of birth and death, there was nothing inscribed on the black granite. I had hoped maybe it would quote something Throssel once said: “My one great desire is to truthfully record Indian life by means of pictures and stories.”

I left a gift of sweetgrass on the stone and made a promise to dedicate my life to a continuation of his work.

View more than 1,700 Richard Throssel images via the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center website.

From the February/March 2017 issue.