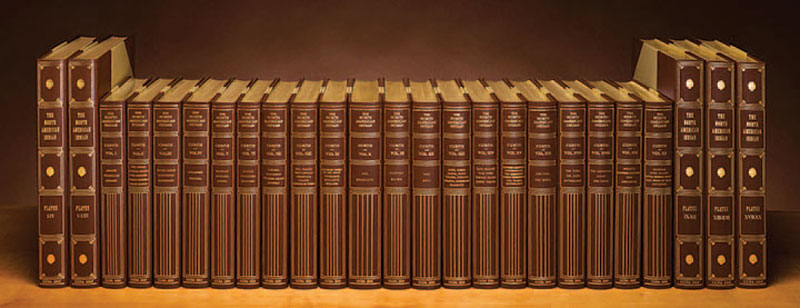

Edward S. Curtis’ magnum opus is among the greatest achievements in publishing history. Christopher Cardozo’s word-for-word, picture-by-picture re-creation may not be far behind.

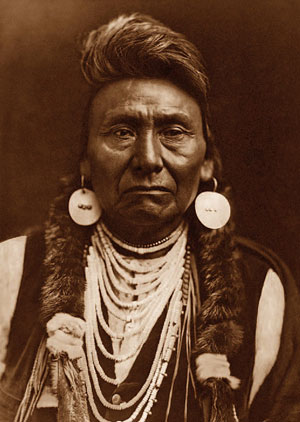

Edward S. Curtis is best known for his turn-of-the-century photography of the American West and its indigenous people. But to simply remember him as a photographer is to overlook the incredible work he did as an anthropologist, ethnographer, historian, and writer, achievements that culminated with perhaps the most ambitious one-person publishing project in the continent’s history: The North American Indian.

Christopher Cardozo is widely recognized as the world’s leading expert on Curtis and has authored nine monographs and created exhibitions that have displayed in more than 40 countries over the four decades he’s been collecting Curtis’ work. He’s all too aware of how much time and work Curtis put into his magnum opus between 1900 and its completion in 1930. The project, Cardozo says, “cost Curtis everything he held dear.” In anticipation of the 150th anniversary of Curtis’ 1868 birth, Christopher Cardozo Fine Art is republishing the encyclopedic set in its entirety.

Some numbers that put into perspective the work that went into the re-creation of The North American Indian: Like the original, each set consists of 20 volumes, 2,234 images, 5,023 pages of text, and more than 2.5 million words. The original 20 portfolios have been consolidated into five portfolio volumes for ease of access. It took nearly 10,000 hours to research, typeset, lay out, prototype, and proofread the republication, and Cardozo expects completion of the project to require 30,000 hours from his team of about 15 people creating and hand-interleaving nearly 200,000 prints, one sheet at a time. All that work is for a print run of 75 (plus eight artist proofs), with each set costing about $28,500 and projected to go up in price before the custom edition is sold out. A less-expensive reference edition is likely after the completion of the custom version.

Cardozo anticipates that the republication will be purchased primarily by serious collectors, museums, libraries, and universities, which now include Harvard, Northwestern, and the University of California, Berkeley, among others. It’s quite a bargain when compared to one of the 200 or so remaining original sets of The North American Indian, which Cardozo says can climb past $2 million for a set in good condition.

The project began about three years ago when Cardozo created simple facsimiles of two different volumes for a couple of clients. The buyers were very happy with the outcome, as was Cardozo, but he knew he’d have to dig deeper to do a worthy full republication. Using three different well-preserved original sets of The North American Indian as well as original photogravures and platinum prints, the goal was to combine the best elements of all available sources. The team bumped up the type size a bit and used a more legible selection in the same font family, along with a few other modernizations such as using one space instead of two after periods. They even had to create a new digital typeface for certain symbols in Native languages that didn’t exist in any extant fonts. The goal was to create a beautiful set of books in its own right and to make it more legible and accessible for modern readers and collectors.

Here’s more from Cardozo about the project.

Cowboys & Indians: How did you come up with 75 for the number of copies? It seems like, with it being such an undertaking, you’d want the books to be more widely available.

Christopher Cardozo: I wish I could tell you it was a really intelligent, well-informed decision. [Laughs.] I really didn’t know what I was doing, other than I thought it would be a good idea. The advice I got really underestimated the amount of work that was going to be involved, and the expense, so I didn’t realize quite what was going to be involved. That said, as it turns out, I think it’s a pretty good number. We’re finding there are a number of collectors and institutions that are subscribing, but there are a number of others that would love to have it but just don’t have the budgets. Ultimately, we expect that we’ll create a reference edition where all production will be mechanized. We certainly hope that we’ll place many of the reference sets with collectors and institutions that can’t do the custom edition.

C&I: What do you think Edward S. Curtis would think of the finished sets?

Cardozo: I think he would be thrilled. ... [H]e really wanted this work to be seen. He wanted people to read about, learn about the culture, the lifeways, the individuals, who they were, what their lives were like. The original sets are oftentimes hard to get to see. They’re mainly in institutions, and there are security and preservation concerns. I’ve had people call me and say they were going to have to wait up to five weeks to see one of the original sets, and then typically, the institution could only free up staff time for two hours, which only gives you time to look at one of the volumes, or one or two of the portfolios. This is a way that many, many more people will be able to see a high-quality re-creation of the original.

C&I: What motivated him to take on such a monumental task?

Cardozo: He really loved Native people and their lifeways. He had a watershed experience in the summer of 1900. He went with a famous anthropologist, George Bird Grinnell, to Montana. He was with Native people, who were very open about their religion, their mythology, their personal lives, their ancestors, their lifeways. He was able to witness some very important ceremonies, like the Sundance ceremony, which was being outlawed by the U.S. government. So in that two-week period, he had a really deep, deep view into Native American life and great connections with individual Native people. That impassioned him. He realized that this incredible culture, these incredible people were, in many ways, disappearing. Good estimates are that there were about 250,000 Native people on this continent in 1900. There had been close to 25 million Native people here in 1600. So there was a very real chance that not only would their culture disappear but perhaps even the people would disappear. ... He dedicated much of the rest of his life to their culture, and he knew it had to be done quickly, and he had the sense that no one else could do it the way he could. There were thousands of people who photographed Native Americans, and there was nothing remotely similar to what he did.

C&I: Did this project reveal anything you hadn’t realized or known about Curtis before, or that changed your perception of him?

Cardozo: [D]oing this gave me a deeper sense of what was involved, and how complicated, and how demanding it was. It gave me a better sense of why it took 30 years. It’s just amazing that one man with a sixth-grade education who was not personally being paid a penny to do it by J.P. Morgan or anyone else — he had to raise his own money for his own salary and everything else — that one person could do that. It deepened my appreciation and admiration for who he was and what he did. ... Having to deconstruct this whole body of work in order to re-create it, we got a sense of how much work really went into it. I came away from it with an even deeper respect and gratitude for Curtis and what he accomplished.

For more information about the republication of The North American Indian, visit www.edwardcurtis.com.

From the February/March issue.