It came down to three very different riders vying for the saddle-bronc championship title and the silver saddle when the official decision clashed with the people’s pick.

The day was September 14, 1911. The roar swelled until it filled the new Pendleton arena, as thousands of angry voices thundered in unison, “People’s Champion! People’s Champion! People’s Champion!” The judges had already announced the winner of the saddle-bronc event, the most prestigious competition of the entire roundup, but the crowd did not agree with their choice. Now they were going to do something about it.

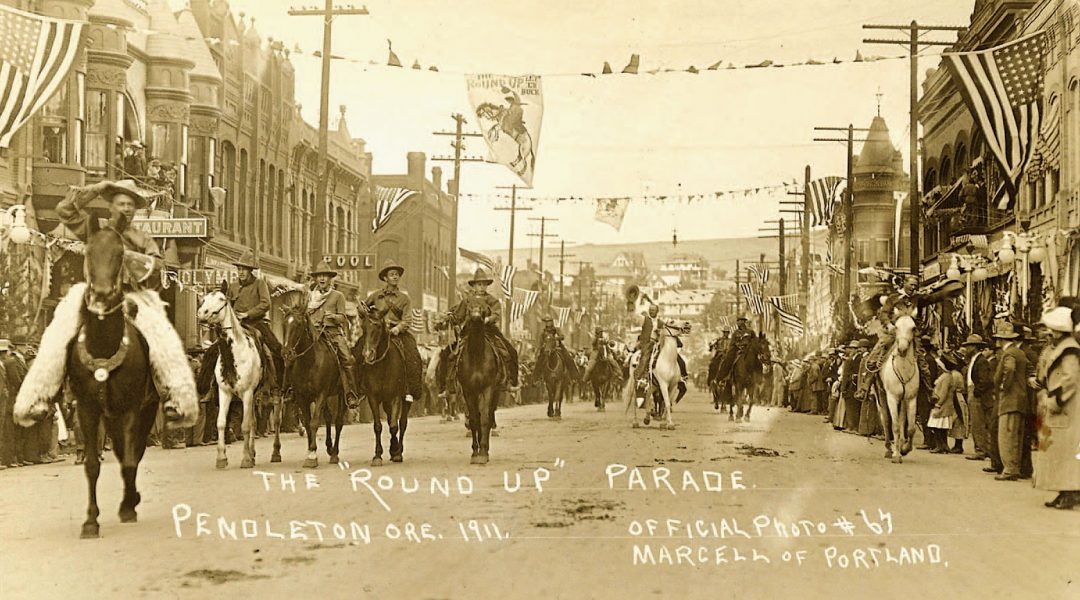

The Pendleton Round-Up was a new attraction. It had been established just a year before, in 1910, at a time when the historic West was fast fading into a wistful, romantic memory. The city fathers of Pendleton, Oregon, drawing their inspiration from the Wild West extravaganzas of such showmen as William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Gordon “Pawnee Bill” Lilley, laid out the plans for a local show of their own. They formed a nonprofit organization ambitiously dubbed the Northwestern Frontier Exhibition Association and built a large arena. They then sold shares in an event designed to showcase the skills of the cowboys as well as the customs and traditions of the Native American tribes of the Northwest.

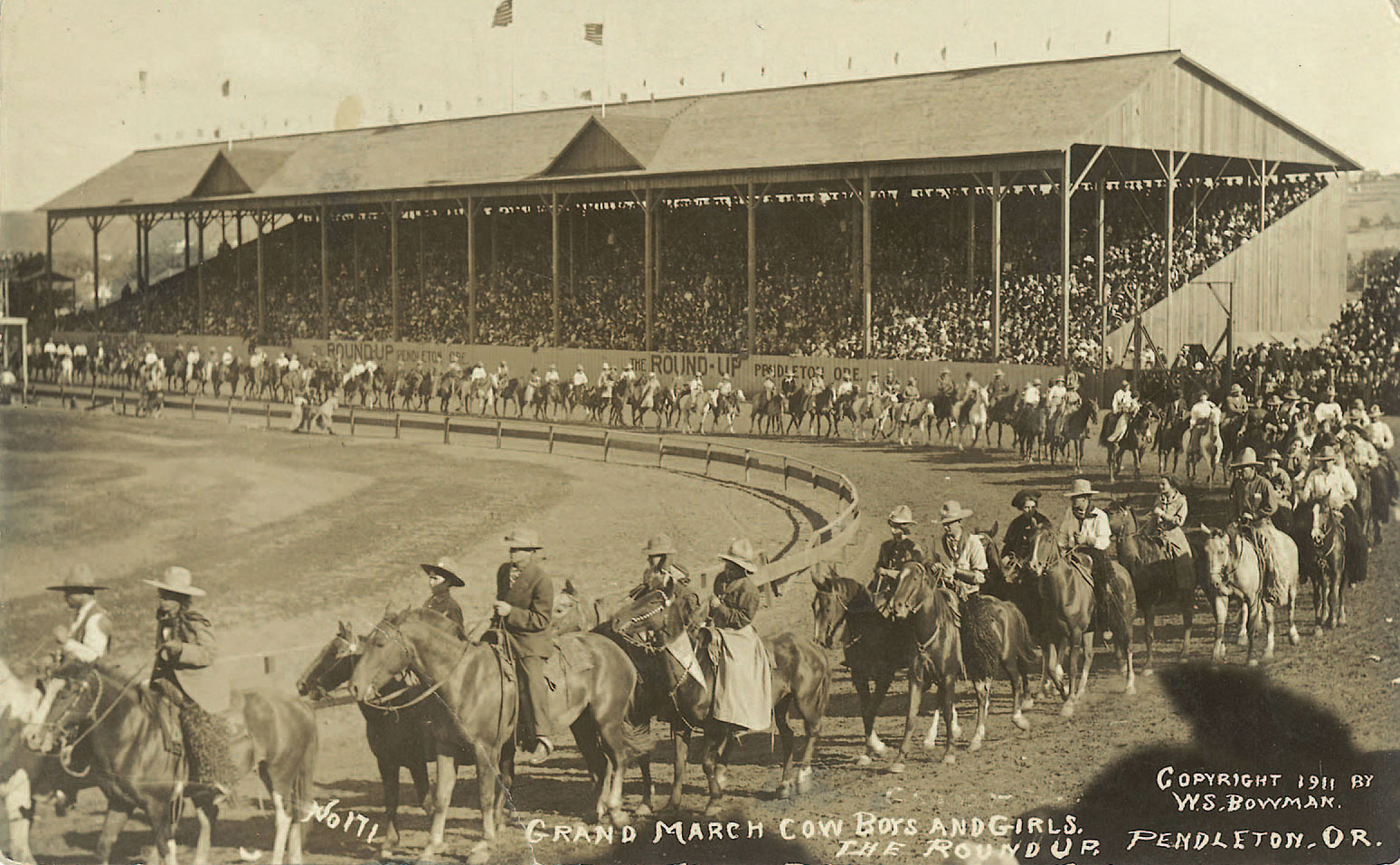

The show opened in late September and was an unqualified success, drawing scores of enthusiastic competitors and some 7,000 attendees. The Indian participants performed ceremonial dances and staged horse races, and the cowboys competed for cash prizes in a series of events. The most popular was the Saddle Bronc Championship of the Northwest, with a $250 silver-mounted Hamley saddle going to the winner.

By the following year, word had spread, and dozens of the region’s most skillful cowboys and cowgirls added their names to the lists. Not surprisingly, there were so many viable contestants signed up for the saddle-bronc event that an even dozen made it to the semifinals and a chance to win the year’s top prize. It was a stunning E.L. Powers & Sons saddle, with silver trim adorning its fork, cantle, jockeys, skirts, and long tapaderos.

The Contestants

Eventually, all but three riders were eliminated. Each of the three men in contention for the silver saddle and the champion’s title was an outstanding horseman in his own right. They could not have been more unalike: a middle-aged Nez Perce named Jackson Sundown; John A. Spain, the young son of an Oregonian pioneer family; and a local African American cowboy named George Fletcher.

Sundown was unlike anything the crowd had seen inside a rodeo arena. At a lean, wiry 6 feet, he was tall for an Indian, with a sharp-featured, handsome face framed by two long, thick black braids. As nearly as anyone could calculate, he was born in or around 1863, making him about 48, although he moved with the grace and ease of a much younger man. He had a unique fashion sense, and when not clothed in traditional tribal apparel (which he wore at his wedding and when posing for artists), his signature outfit consisted of a wide-brim hat, its crown wrapped in a silk scarf; another patterned scarf knotted around his neck; intricately beaded gauntlets; a dark shirt covered in bold white ovals; and spotted wooly chaps. On anyone else, such an outfit might have occasioned ridicule; on Sundown, it worked.

His father was Nez Perce, but he was half Salish on his mother’s side. Naturally, his tribal name was not Jackson Sundown, nor was it “Buffalo Jackson,” the first Anglo moniker he had assumed, at a time in his youth when he reputedly rode buffalo for sport. He was a nephew of the legendary Chief Joseph and at age 14 had accompanied the tribe when Joseph led it toward Canada in an attempt to elude the U.S. Cavalry and the government reservation. Sundown was present at each of the fights with the pursuing troops, including the final confrontation — the so-called Battle of Bear Paw — in which Gen. Nelson Miles raked the fleeing Nez Perces’ defenses with exploding artillery shells. When Joseph finally surrendered just 40 miles from Canada, Sundown made his way north of the border to join Sitting Bull and his exiled Sioux.

From boyhood, Sundown had earned a reputation as a proficient horseman, and after returning to the United States, he made his living as a breeder and breaker of horses. One old-timer told of owning a buckskin horse that had unceremoniously thrown all comers, until a tall Indian wearing braids and a blue serge suit approached. He bowed when introduced, mounted the rank mare, and rode her to a standstill. “He then dismounted,” recalled the old man, “looking just as neat and unruffled as he had before the ride.”

As Sundown’s reputation as a bronc-buster grew, other riders would refuse to compete against him, so he staged exhibition rides for pay. For side money, he’d bet that he could put a silver dollar between each boot and stirrup and keep the coins in place throughout his ride. Whoever thought up the phrase “There ain’t a man who can’t be throwed” had never met Sundown.

Born in 1881, John Spain was the son of a Nebraska farm couple who made their way to Oregon by covered wagon. Rather than live under their abusive father, John and his older brother, Fred, each ran away from home at a very young age and remained inseparable throughout their lives. Both were natural bronc-busters and over the years earned prize money in several local competitions.

John grew to become a burly 6-footer and earned a reputation, as biographer Rick Steber put it, for “overpowering [bucking horses] with his brute strength and fierce determination. ... When it came to riding broncs ... John was the unmovable object.”

In 1902, the brothers attended a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Baker, Oregon. It made a strong impression, and they determined to enter “the show business.” Over the next two years, the two — still in their early 20s — saved enough of their wages and prize money to buy a ranch in Union County, Oregon, and stock it with bucking horses. In Sumpter, Oregon, on Independence Day, 1904, they offered the first performance of their own modest pageant: The Spain Brothers, Last of the Real Wild West Shows.

Although well-reviewed, the first show was poorly attended. Nonetheless, the Spain boys swiftly refined their approach, thrilling crowds throughout the state. John was an expert with a riata and staged demonstrations both mounted and afoot. Two of the most exciting events — in which the brothers often competed against each other — were the four-horse chariot races and the hippodrome races. Sometimes referred to as “Roman riding,” the latter featured a rider standing astride two horses as they galloped around the arena.

By 1910, the brothers had established a reputation for both a strong business sense and consummate skill in the arena. The Umatilla County sheriff, Tillman “Til” Taylor, offered to hire their bucking stock for use in the brand-new Pendleton Round-Up and invited them to sign up for the various events. They accepted.

Fred won the prize for Most Typical Cowboy, while John took first place in the Wild Horse Race. He was disqualified in the popular saddle-bronc event, when one of the three judges claimed he had “pulled leather” — touched the saddle horn with his off hand. John was indignant, but the decision stood. He would, however, be back to compete in the feature event the following year but with unexpected results.

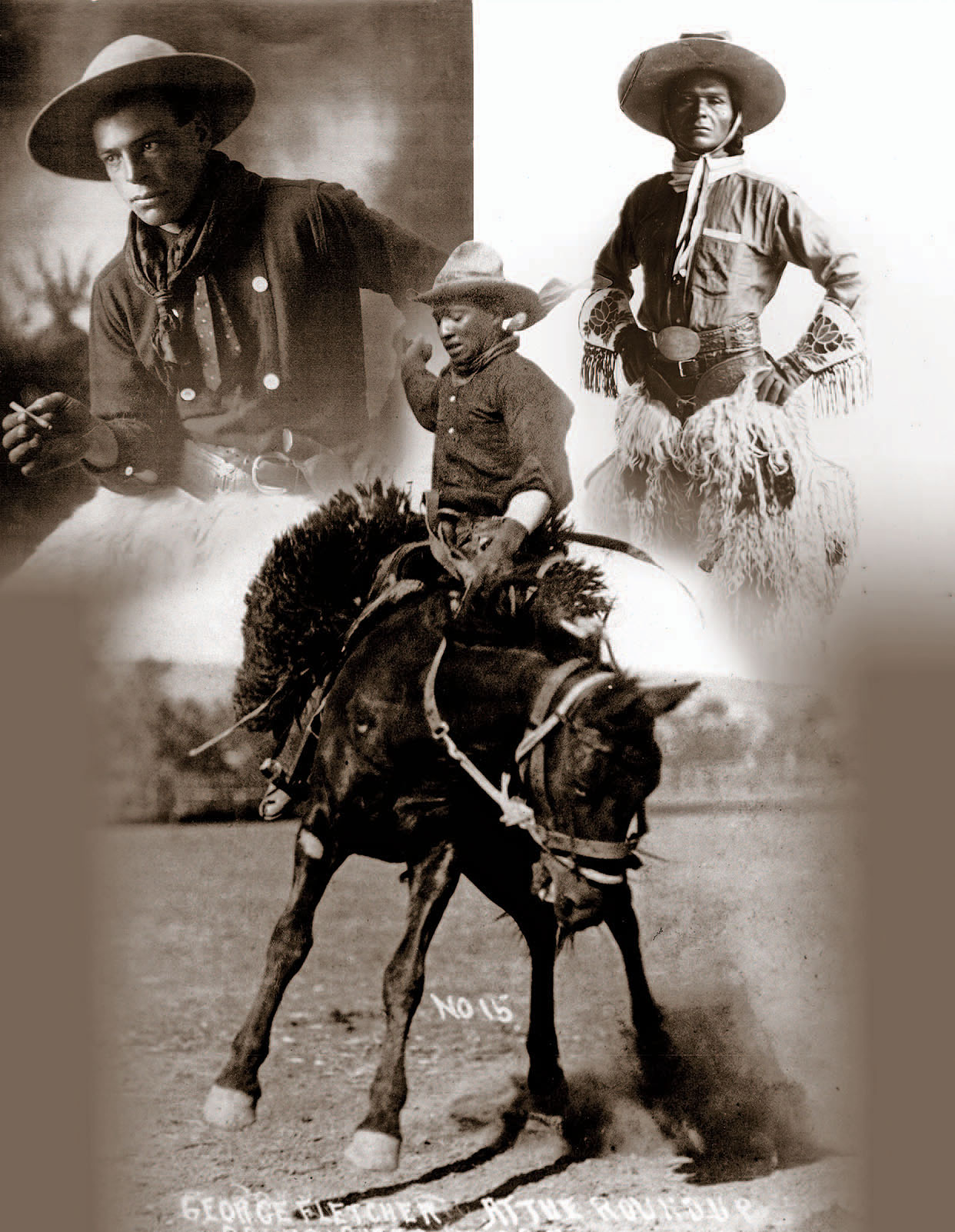

George Fletcher was born in 1890 into an African American family living in St. Marys, Kansas. With the Oregon Trail stretching off to the west, the family moved to Pendleton when he was still a boy. He attended public school just long enough to suffer racial slurs and attacks before enrolling in the new mission school on the Umatilla Reservation.

Fletcher quit school after the fifth grade and grew up living with friends on the reservation. He learned the Indian language and customs and in the process became a formidable horseman. At 19, he took third place in the saddle-bronc competition at Pendleton’s Eastern Oregon District Fair, earning prize money ($15) for the first time. A year later, he placed fourth in the newly inaugurated Pendleton Round-Up.

With the passage of time, Fletcher would stage exhibition rides, forking everything from a horse to a bull to a buffalo. On one occasion, he and another black horseman rode the same bucking horse simultaneously, each facing in the opposite direction.

By the time the 1911 Round-Up’s bronc-busting competition came around, Fletcher was well-known to most of the locals.

The Ride

For the final round of the 1911 saddle-bronc event, Sundown drew a rank little bronc named Lightfoot. The horse tried every trick he knew to deposit his rider, including attempting to bite his leg. In those days, there was no eight-second limit: The cowboy rode until the animal quit bucking. After nearly half a minute, after all else had failed, Lightfoot ran straight at one of the judges’ mounts. The resulting collision threw Sundown to the ground, knocking him momentarily unconscious. Although the judges could have given him a re-ride, they simply chose to disqualify him.

Spain was next out of the chute, atop Long Tom. A wooden fence separated the track from the arena, and Long Tom broke through it, with the “unmovable” Spain still aboard. It was an impressive ride, although several people in the stands claimed to have seen him pull leather as the horse bolted through the fence.

The final contestant was Fletcher, riding Del. It was a disappointing performance. The horse, which had performed well in the past, simply refused to buck. The crowd, who had cheered wildly at Fletcher’s qualifying ride, screamed for the judges to assign him another animal. After extensive discussion, the reluctant judges ordered a bronc named Sweeney to be brought out for Fletcher.

The resulting ride sent the crowd into a frenzy. To screams of “Let ’er buck,” as the local newspaper later stated, “Fletcher rode Sweeney with such ease and abandon that the crowd shouted itself hoarse. He is as loose and limber as a rubber band. ... In addition, he scratches his animal fore and aft, the rowels of his spurs traveling from shoulders to rump.”

To the crowd’s amazement and deep disappointment, the judges awarded first place to Spain, with second place going to Fletcher. When Spain rode past the grandstand astride his prize saddle, the crowd applauded. But, as the paper would report, as the “little Ethiopian” passed them, “[t]he crowd yelled and bellowed their admiration ... .” Many, including Fletcher, would always believe that the judges had simply refused to grant the title to a black man.

The crowd, however, was not finished with Fletcher. Grabbing his hat, Sheriff Taylor cut it into small pieces and sold each piece for $5 to members of the audience. When all the pieces were sold, he turned the proceeds over to Fletcher. It totaled around $700 — more than twice the value of the silver saddle given to Spain. As they chanted “People’s Champion” over and over, it was clear who they felt deserved the World Saddle Bronc Champion title.

Down The Trail

The following year, Spain lost his right hand in a roping accident but continued to ride successfully in rodeo competitions. After sustaining a leg injury while serving in World War I, Fletcher quit the rodeo but remained a cowboy all his life. Sundown finally won the champion’s saddle at Pendleton in 1916; he was 53 years old. Sundown died in 1923, the year before Congress voted to make American Indians citizens of the United States.

In 1969, Fletcher was among the first cowboys to be inducted into the newly established Pendleton Round-Up and Happy Canyon Hall of Fame, followed in 1972 by Sundown, and in 2011 by Spain. In subsequent years, both Fletcher and Sundown have been honored with membership in the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum Hall of Fame.

For more information, the author recommends Last Go Round: A Real Western by Ken Kesey and Ken Babbs (Viking, 1994) and Red White Black: A True Story of Race and Rodeo by Rick Steber (self-published, 2013).

From the October 2016 issue.