Some special vintage firearms with singular Western credentials are on the market — including a war-trophy rifle once belonging to Chief Black Kettle that became part of Custer’s personal collection.

What makes a gun collectible? For most collectors, the many possible factors include make and model, condition, rarity, history, artistry, and craftsmanship. How to weigh those factors is subjective, but a strong tie to the singular history of the American West puts a covetous smile on the fascinated face of a gun aficionado almost every time. Whether the stock sits nicely against your shoulder and cheek hardly seems consequential when that stock is embedded with 150-year-old tacks that convey a message in Cheyenne pictographs and the gun’s provenance is “passed down through the Custer family for generations.”

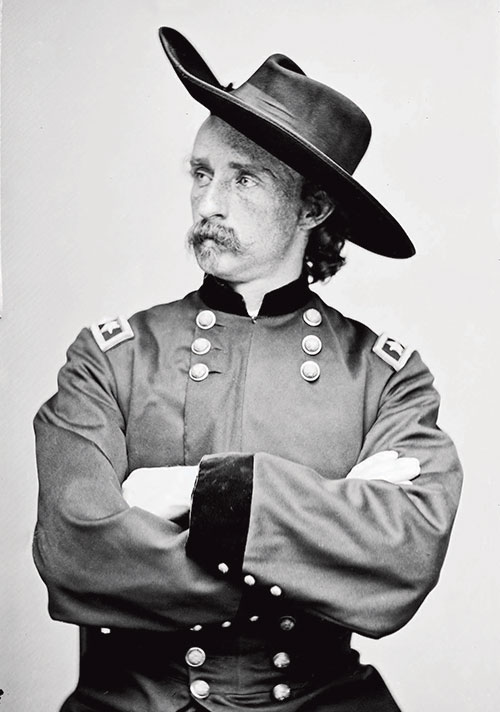

Such is the case with the Sharps George Armstrong Custer Indian Capture Carbine — a real firearm-as-showpiece/museum-piece.

“This gun is a national treasure,” says Fred Holabird of Holabird Western Americana Collections. And not just because he and his company have been tasked with marketing and auctioning the gun. A classic trophy of war attributed to the great Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle — the chief of the Southern Cheyenne known as a dedicated negotiator for peace for his people and ultimately as a victim of Custer’s 1868 massacre of a peaceful village on the Washita River just outside of present-day Cheyenne, Oklahoma — the Custer Carbine stands out for its association with both the chief and the “Boy General,” its fine condition, and its stock decoration.

Sharps No. 68457 was part of Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s personal collection of arms and memorabilia, one of some 20 known guns that belonged to him. Picked up by an unknown person, the gun was taken by Custer from a wagon full of Indian artifacts. “The gun came through the Custer family to well-known Western gun dealer/collector Dick Reyes, who co-owned Fort Carson Antiques in Carson City, Nevada,” Holabird says. “While most of the other Custer artifacts Reyes inherited from the Custers were ultimately sold through Butterfields, the Custer Carbine remained in his collection.”

The unique decoration alone would be reason enough to hold on to the rifle. “The tack pattern on the gun reflects that it was special — obvious to any Indian or white who owned or saw it at the time,” Holabird says. “It’s distinctly set apart from other tack-patterned arms by the highly ornate nature of the placement of the tacks, their neatly executed pattern, and the sheer number of tacks — far more than what experts have previously encountered. It’s quite refined — what one would expect in the possession of a chief — with more elaborate decoration than any other known example.”

The neatly placed brass and iron tacks make the firearm “the most embellished of any known example of Indian Sharps.” Primarily on the right side of the oil-finished walnut butt stock, the tack design turns out to be as historically and culturally important as it is artistically appealing and unusual.

In the past, it was assumed that the tack patterns on “Indian capture guns” were all Native American art. Not so. They are a language — as Holabird was astonished to discover recently. “At the Las Vegas Antique Arms Show [in January 2016],” he says, “we met Wendell Grangaard, who has been handed down the pictographic language of the Cheyenne and Sioux from Oglala Nicholas Black Elk. We did not know [Grangaard] existed, nor did anybody else. This marked the first time anyone has found out that the language of pictographs is still alive. He saw the gun, became excited, and returned the following morning with the translation of the beads and marks on the gun.”

Christopher Kortlander — founding director of the Custer Battlefield Museum, which is located on private property in Garryowen, Montana, near the Little Bighorn Battlefield and the site of Sitting Bull’s camp — was present with Holabird for Grangaard’s discussion of the Sharps Custer Carbine. “The information Wendell Grangaard has recorded through his impeccable anthropological diaries further supports the model that as indigenous peoples moved through the hunting and gathering phase in their cultural development, they seem to have responded to a common goal — to create an unspoken language that would survive in perpetuity,” Kortlander says. “Through direct descendant oral history, Wendell has recorded the key that appears to unlock the unwritten code of the Plains Indians. In my 35 years in this field, I have never known of any such documented key to unlock the cryptic language of Plains Indians symbols. This is a major breakthrough.”

It was no less a revelation for Grangaard, who wrote Documenting the Weapons Used at the Little Bighorn (Mariah Press, 2015). “In examining the Sharps Model 1859 carbine S/N 68457,” he wrote in a subsequent report, “I found that it was marked with the band marks of the Southern Cheyenne Indian chief Black Kettle in brass tacks. These marks are on the right side of the stock, as per Cheyenne tradition. Within the band mark are two symbols that look like crosses — one large one that indicates a society, which in this case is the Dog Soldiers, which was the society Black Kettle belonged to. The smaller cross indicates he personally headed the society.

“On the opposite side (the left side) of the stock, I found the society mark of Crazy Dogs, which is indicated by seven brass buttons in a row along the butt plate. This was the second society Black Kettle belonged to. Up the stock on the left side is a togia symbol for chief, because this carbine belonged to a chief. On the stock and forearm of S/N 68457 are many symbols in togia. One of these symbols corresponds to the testimony of Monahseetah, Black Kettle’s daughter [according to Cheyenne oral tradition; other historians claim she was the daughter of Little Rock]. She said she placed the togia protection symbol of the Thunder Being on her father’s rifle for George A. Custer (like she did on all Custer’s weapons). Benjamin Black Elk once told me it was important to use the Lakota words he told me in telling the stories because the Lakota and Cheyenne languages have special meanings which are hard to describe in English. He told me the sacred language, which was not understood by most Lakota. This was togia — to talk and write the strange language of a wakan (holy man) using oowa (marks).”

Grangaard’s observations about the mysterious togia on the Sharps Custer Carbine were in corroboration with gun markings described and reproduced in Lawrence A. Frost’s The Court-Martial of General George Armstrong Custer (University of Oklahoma Press, 1979). The discovery led eminent firearm expert Robert L. Wilson, co-author with Holabird of a book on the Custer Carbine, to make a video about the gun with Holabird, Grangaard, and Kortlander.

The meaning of the symbols is a window into Western history — and another suggestive indication of the ways in which the much-mythologized Monahseetah may have figured in to the life of Custer. Historians continue to debate whether Custer did indeed take her as his sexual partner (until wife Libbie ostensibly nixed the arrangement) and tend to be skeptical about the charge that he fathered a child — variously called Yellow Swallow or Yellow Bird for his fair coloring — with her. Those titillating rumors aside, Grangaard says he learned how Custer came to be in possession of Black Kettle’s gun when members of Monahseetah’s family, requesting anonymity, told him about her life 50 years after her death in 1922.

“The first time I went to Creeping Panther’s [Custer’s] tent,” Grangaard imaginatively relates in first-person as if he were Monahseetah, “he left for a short time, so I looked at all of his belongings. I found my father’s rifle sitting in the corner of the tent. I picked it up just as Custer returned and I turned to him and said, ‘This is Black Kettle’s rifle. I know you did not kill him because I saw who killed him.’ I don’t think he understood all that I said, because he replied to me in Cheyenne, ‘It was in the wagon.’ Months later, after we began to understand one another, he told me he had taken my father’s rifle out of one of the wagons for a war trophy. I told him that a great war chief should have the rifle of a great chief.”

Whatever the conjecture about his personal life and controversy about his military role, the trophy rifle that was passed down from Gen. George Armstrong Custer through his family remains a testament to the powerful history he played a part in.

For more information on the Sharps Custer Carbine, visit Holabird Western Americana or contact Fred Holabird at 775.851.1859.

From the May/June 2016 issue.