Did the famous turn-of-the-century photographer stage or romanticize his portrayals of Native Americans? To biographer Timothy Egan, that's beside the point.

Events that occurred 100 years ago can still ignite controversy, particularly when they have to do with the way history regards whole cultures. Which is why Timothy Egan’s recent biography of legendary photographer Edward Curtis is so important. Egan finally sets the record straight on all sorts of debates. Why Curtis staged his Native American photos. How a Crow Indian helped Curtis uncover the truth about Custer’s bad decisions at the Battle of Little Bighorn. What motivated a sixth-grade dropout to devote his life to creating a 20-volume series chronicling the North American Indian, an undertaking that led to his dying penniless and ruined.

Egan, a Seattleite like Curtis, was up to the nonfiction challenge. A longtime journalist, he ran the Pacific Northwest bureau of The New York Times for years; his 2006 book about the Great Depression, The Worst Hard Time, won the National Book Award for Nonfiction; and a series on race that he contributed to won The New York Times a Pulitzer Prize for national reporting. For Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis, he visited 80 Indian tribes just like Curtis did a century prior.

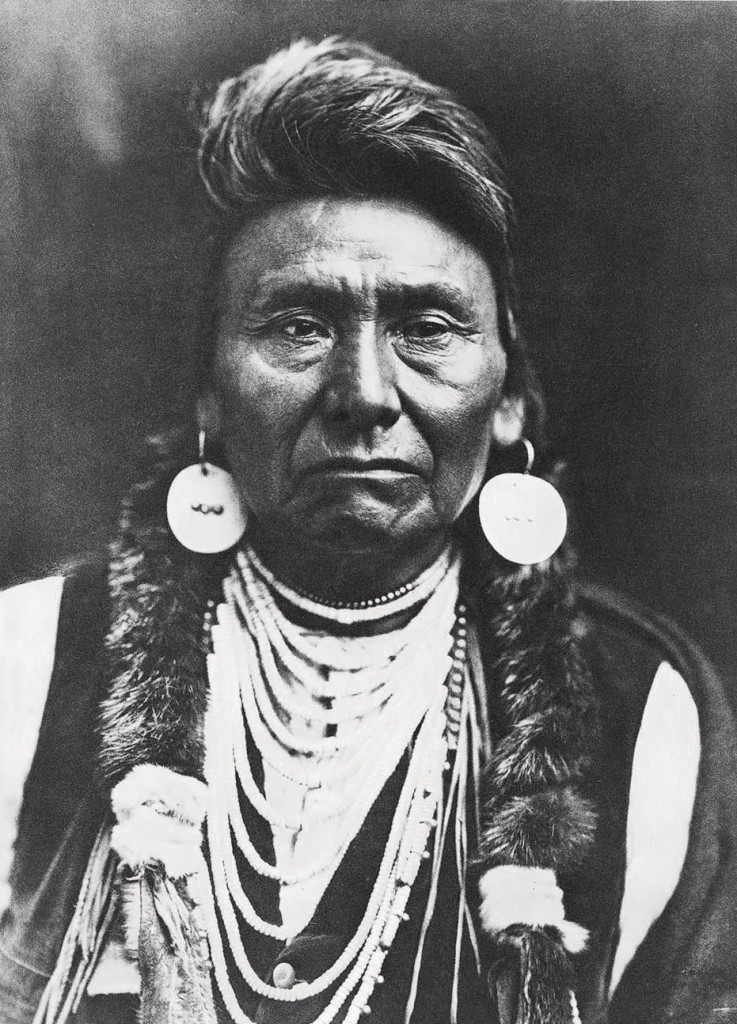

Why Curtis, and why now? In 2010, a single Curtis photogravure of Chief Joseph sold for $160,000. In 2012, a complete set of Curtis’ opus, The North American Indian, including 20 text volumes and 20 folios, brought $1.44 million, more than any other single lot sold at Swann Auction Galleries in its 70-year history and topping the $1.4 million a full set brought at Christie’s in 2005. While Curtis’ photographs keep escalating in value, Egan was more interested in the inside story of the man who walked away from his thriving Seattle photo studio to venture into remote terrain. We talked to the author about what motivated Curtis, the lengths to which he went, and why he matters so much today

Cowboys & Indians: What motivated Curtis to take Indian tribal photos from 1900 into the 1930s?

Timothy Egan: His goal was to capture the life of the original inhabitants at a moment before they all looked like everyone else. Think about the time — the start of the 20th century, 113 years ago. There were less than 250,000 Native Americans in the whole U.S. then. The conventional wisdom was that they were going to disappear within a generation’s time.

C&I: Are there misconceptions about Curtis to clear up?

Egan: Yes, there was an academic debate and there are still some people who think that because he posed people, somehow his pictures are phony or overly romantic. My response to that is that he was seeking the essence and character and humanity of these First People. Sometimes he would ask someone to put on a headdress or some leggings. To me it’s no different than if he was photographing someone in Scotland from the MacGregor clan and he said, “Do you have a kilt that your grandfather used to wear?” Would that be phony? No, that’s the essence of the MacGregor clan.

C&I: Still, people criticize that Curtis staged and romanticized his photos.

Egan: Well, he doesn’t have a lot of happy faces, except in the North with some of the Eskimo photos. It’s not like he shows them having a great life. Look at the photos of Chief Joseph or Geronimo. You see so much in their faces: the humanity, the sense of loss and frustration and betrayal.

C&I: He was trying to make the photos striking, I imagine ...

Egan: Yeah, he’s got a lone person at the edge of a cliff, or a chief alone on a pony. His intent, as he said, was to show them in the context of nature.

C&I: What did Native Americans at the time make of Curtis, and how is he viewed now?

Egan: When he started off the project in 1900 going to Montana, he was not well-received. He was a little too young, a little too eager, a little too in their face. They would throw dirt at his camera and play tricks on him. They didn’t trust him. Then as the project grew and the word spread that there was this “shadow catcher” and he was taking extraordinary photographs and preserving Indian life, they would solicit him. Remember, he said he wanted “to make them live forever.” Now, 100-plus years later, they appreciate him for preserving that moment in their culture just as it was disappearing. An example: The Tulalip tribe in Washington state north of Seattle opened this huge brand-new wing of their casino, and when you walk in, the very first thing you see is this wall-size picture that Curtis took of their tribe in about 1907 of them in their canoes pulling in salmon nets! They appreciate that he captured their moment and the humanity and dignity.

C&I: Any other examples?

Egan: When the Hopi went to revive their language, the Hopi scholars used the audio recordings that Curtis took. A woman who teaches Blackfeet history in Montana uses Curtis pictures as a way for people to connect to their grandparents. ... That’s why the academics [who criticized Curtis] were full of crap. Go to the subjects themselves. They appreciate the photos.

C&I: Did Curtis form any lasting relationships with his Native subjects?

Egan: He had two or three really strong friends, like Alexander Upshaw, who helped him with the Custer story. Upshaw was a full-blooded Crow who was educated at the Indian School in Pennsylvania, tried to be white and he couldn’t do it, and he ended up going Native or “back to the blanket,” as they say. He was Custer’s best friend. Not just Native best friend, but best friend. Upshaw spoke both languages. Curtis figured out what happened at that iconic Custer battle, and he got it right because of Upshaw. They figured out that Custer had made some terrible mistakes and wasn’t just caught unaware by this large tribe but may have doomed them by watching the other [military] flank die.

C&I: How about any near misses? Didn’t Curtis flee a canyon near Chinle, Arizona, when a Navajo baby almost died during childbirth and they blamed it on his presence?

Egan: That was a terrible incident for him. Canyon de Chelly is one of the most stunning places in America. The Navajo have lived there for a long time, and a handful of Navajo families still run sheep through the canyon floor.

C&I: What about the Apache medicine man Goshonné, who was probably killed because he told Curtis secrets?

Egan: Yeah, he betrayed his people. Here’s a high priest taking money from a white man to tell him the secrets of their religion. Curtis was so intent on proving to the experts that the Apache had a religion. But I think he realized he crossed the line. His intrusions led to some bad things. Consider the context, though, that it was illegal for them to practice their religion — a total violation of the First Amendment. Wrong! The government wanted to assimilate the Indians and get them to be white citizens. Curtis was going in the opposite direction. He wanted to record what the U.S. government was trying to break up.

C&I: To what lengths would Curtis go to get his images?

Egan: He would do anything! He had three or four near-death experiences. He would have horses pull around this wagon with all his photographic equipment, and he was in a gully in the Southwest one summer, and one of these monsoons came and washed the wagon downstream and he was smashed against the rocks. Another time he was descending the Grand Canyon in pursuit of the Havasupai, a little tribe who live at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. To this day the mail is delivered there by mule. His horse tipped to one side, and he lost one of his cameras and he nearly went with it. The worst incident was in Alaska when his ship was lost in a storm and the seas iced up, and an obituary was written about him. And he was nearly crushed on the Columbia River before it was dammed. It was a wild and incredibly chaotic river, and he had this little skiff. The people with him quit midriver because they were so afraid they were going to die.

From the April 2013 issue.