Blood, bullets, and buckskin — the story of the Old West is revealed in some of its most infamous showdowns.

It needs to be asked: Of all the heady “Top 10” subject matter we could scour for discriminating C&I history buffs, why gunfights? Well, certainly not because we would ever actually endorse people (even ones with last names like James or Earp) engaging in such grave behavior — at least not without a John Ford-caliber director and a good makeup artist present.

Maybe it’s because we just can’t quite get our heads around the fact that, unlike Burt Lancaster’s winning turn as Wyatt in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral or Robert Duvall’s maniacal portrayal of Jesse in The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, these larger-than-life characters, these wilder-than-anything events, actually existed in some raw, unfictionalized shape or form. They were real. And lethal. And they became an indelible part of America’s Western heritage, like it or not.

And, cringe at the violence or not, they definitely weren’t dull. “There’s nothing as dramatic as life-and-death conflict,” says Western historian Bill O’Neal, author of Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters, which logs about 600 of the biggest bullet skirmishes of the era. “And when you place that life-and-death conflict in an Old West setting, it just makes the drama that much more compelling and irresistible to American audiences.”

Some of these Top 10 gunfights we all know — or think we do. Others we may not. Still others aren’t on the list and no doubt should be. So feel free to set us straight, partner — after checking your six-gun at the door, please.

“WILD BILL” HICKOK VERSUS DAVIS TUTT JR.

July 21, 1865

Springfield, Missouri

A heated, drunken card table quarrel one fateful night at the Lyon House in Springfield, Missouri, led to the most famous — and one of the few — prearranged quick-draw duels in Western history.

Some say it was a dispute over a watch that prodded gambler Dave Tutt into this fatal mismatch with “Prince of Pistoleers” James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. Others say it was over a prostitute. Either way, the short, decisive two-shot battle in the town square the following July evening at 6 p.m. would turn Hickok into a household name. And Tutt into a body lying face down on the road.

“They were about 75 yards from each other with cap-and-ball revolvers when Hickok said, ‘Dave, don’t come any closer,’ ” notes O’Neal. “That’s one very difficult shot with a Civil War-era piece.”

Tutt snapped off the first bullet and missed. Hickok took a split second longer, steadied his gun with his left hand, carefully aimed, and hit Tutt in the chest. And that was that.

“In spite of their extreme rarity, these fast-draw duels became a staple of all those movie scenes where the Hollywood emphasis was on speed alone,” says O’Neal. “If there’s one thing Hickok proved in this singular gunfight, it’s that accuracy always takes precedence.”

EL PASO GUNFIGHT

April 14, 1881

El Paso, Texas

Dubbed the “Four Dead in Five Seconds Gunfight,” one of the most famous instant blood baths of the era was triggered by the murders in El Paso, Texas, of two young vaqueros who had been tracking a herd of stolen Mexican cattle.

Spurred by a large, angry Mexican posse seeking an investigation, a search would lead to the bodies of the missing farmhands at the ranch of Johnny Hale, a known cattle thief. This led to an inquest, with El Paso constable Gus Krempkau serving as Spanish interpreter. At a saloon later on, it also led to some heated words between Krempkau and Hale’s friend George Campbell, an ex-city marshal, who branded the lawman a “Mexican sympathizer.” Also at the saloon was a drunken, unarmed Hale, who suddenly grabbed one of Campbell’s pistols and fatally shot Krempkau from a few feet away.

Enter Dallas Stoudenmire, El Paso’s new marshal, who heard the ruckus from a nearby restaurant and joined the fray with Colt .45s raised. Stoudenmire’s first shot at Hale missed, killing a Mexican bystander. His next fatal shot hit Hale square in the head. Stoudenmire then turned his pistol on Campbell (who had since exited the saloon, claiming this wasn’t his fight) pumping three bullets into his stomach. Four dead in five seconds (or so) — and that was Stoudenmire’s first week on the job.

BATTLE OF INGALLS

September 1, 1893

Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory

Described as “the deadliest battle ever fought between organized banditry and deputy U.S. marshals” in Glenn Shirley’s definitive account, Gunfight at Ingalls: Death of an Outlaw Town, this short but vicious affair left three federal lawmen plus two town citizens dead — marking one of the greatest law enforcement debacles at the tail end of the Old West era.

It started serendipitously enough when members of the recently reassembled Doolin-Dalton Gang — aka “The Wild Bunch” — were discovered hiding out in the tiny young town of Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory.

“This was about a year after the famous shootout at Coffeyville, Kansas, where two Daltons were killed and one was captured during a foiled double bank robbery attempt,” says Robert McCubbin, a founder of the Wild West History Association. “The other brother, Bill Dalton, hadn’t much learned from that. Instead he teamed up with Bill Doolin’s gang, who were essentially an assortment of ex-cowboys who’d turned to robbing trains and banks.”

On a briefly quiet morning, a surprise cleanup crew of heavily armed deputy marshals and other lawmen entered Ingalls in three covered wagons. No words were exchanged when gang member George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb exited the town saloon and narrowly missed the first gunshot. A fatal hail of retaliatory bullets thrashed the lawmen while all but one of the sharpshooting Doolin gang escaped — a battle won in a war soon lost. “Within a few short years, they were all hunted down and killed,” says McCubbin.

NEWTON GENERAL MASSACRE

August 20, 1871

Newton, Kansas

If there’s a single late-19th-century classic gun battle everyone in Kansas is expecting to read about here, it’s the one down in Coffeyville. But for the sake of boosting historical attention where it’s also due, we instead nominate this oft-overlooked saloon brawl by a bunch of no-names in the briefly infamous farming community of Newton.

About 25 miles north of Wichita, Newton logged its wildest year in 1871 during its brief time as an end-of-track railhead on the Chisholm Trail — and the unfriendliest confluence of cowboys and railroad workers in the West.

On August 11 of that fateful year, Mike McCluskie — a railroad foreman, part-time lawman, and full-time hothead —

got into it with a hard-drinking Lone Star gambler known as William Bailey (both men used aliases) over some local election results. A fistfight between the two men in the Red Front Saloon evolved into gunplay outside. McCluskie shot first, killing Bailey and fleeing town. Bailey’s horde of Texas cowboy friends promised to exact their revenge if he ever returned.

Cut to about an hour after midnight on August 20. McCluskie was back. Bailey’s avengers, led by a cowboy named Hugh Anderson, found the man sitting at a faro table at Perry Tuttle’s dance hall.

“You are a cowardly son of a bitch,” Anderson told McCluskie, according to later court testimony. “And I will blow the top of your head off.”

Anderson fired low, hitting McCluskie in the neck. Down went McCluskie, furiously firing slugs. Several more cowboys then opened fire, along with a young friend of McCluskie’s named Jim Riley, who emptied his barrel into the smoky fray.

“It was the ultimate saloon fight — the place just exploded with crossfire,” says Western historian Bill O’Neal. “All that black powder emitting vast clouds of white smoke inside a place like that must’ve been like a fog machine.”

Final toll when the smoke and utter chaos had cleared: five killed and six wounded. Mike McCluskie would live until the following morning, claiming just before dying that his real name was Arthur Delaney — a name just as forgotten.

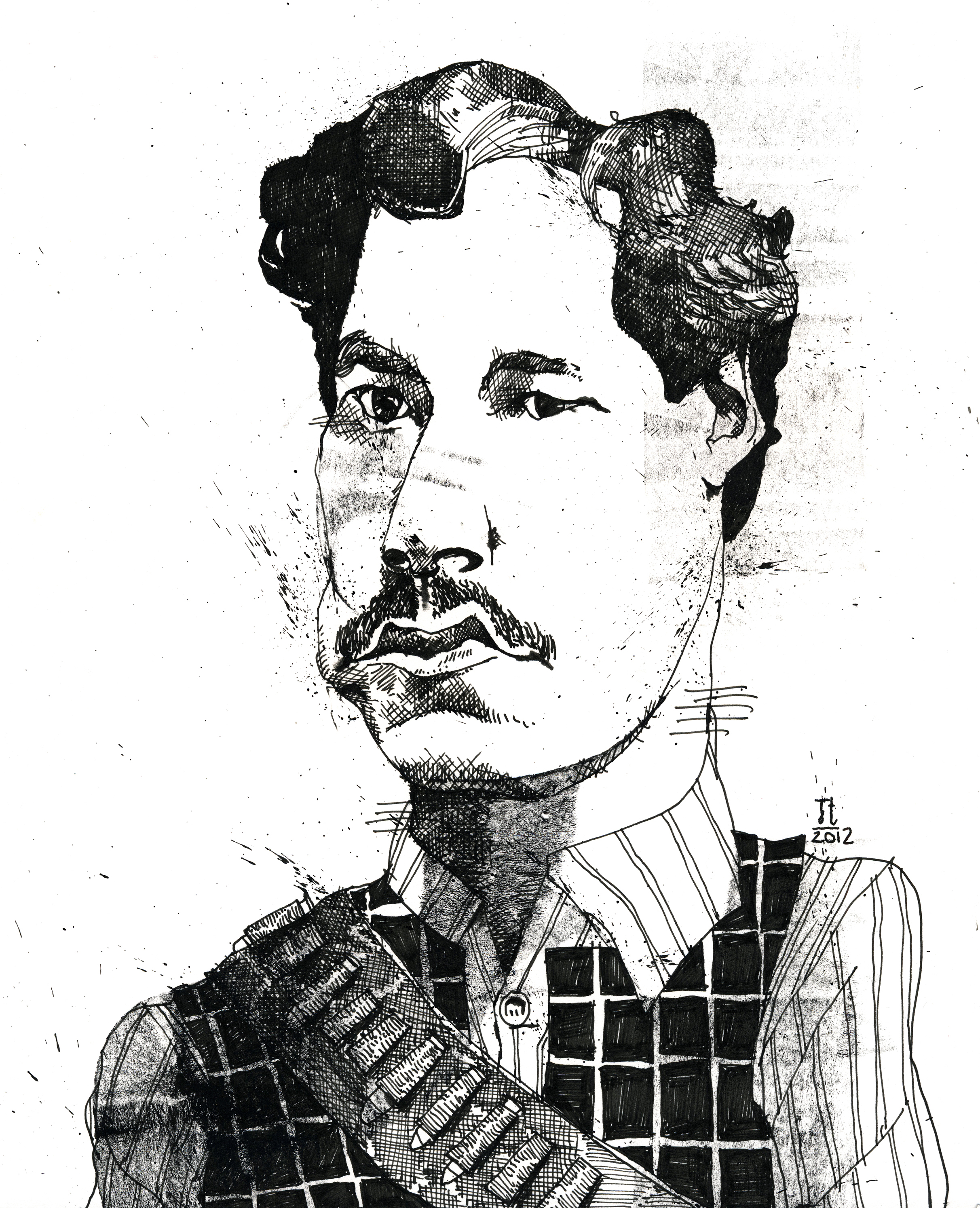

NORTHFIELD BANK RAID

September 7, 1876

Northfield, Minnesota

It was the second worst day of Jesse James’ life. At about 2 in the afternoon, the legendary Missouri outlaw rode into a little town just south of Minneapolis called Northfield with the usual suspects — brother Frank, the Younger boys, and a couple of sturdy accomplices for an easy off-the-radar money grab at the First National Bank.

Instead, a martyred bank clerk refused to open the safe, the alarm was raised, and the mobilized townsfolk all but wiped out the James-Younger gang during a devastating street shootout.

“The citizens had no idea who these guys were — that would only come out later,” says Western historian Mark Lee Gardner, author of To Hell on a Fast Horse and Shot All to Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid, and the Wild West’s Greatest Escape. “What makes this gunfight a standout is that it was just everyday civilians who took on the most notorious, feared, and accomplished set of outlaws to ever ride the American West — and that they defeated them.”

Jesse James (and Frank) would narrowly escape this one, but the loss of the Youngers led to the outlaw’s association with the Fords — and ultimately the worst (and the last) day of his violent life. “It’s safe to say that there’s a direct correlation between Northfield and the end of Jesse James,” says Gardner.

GUNFIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL

October 26, 1881

Tombstone, Arizona Territory

The law — crooked and homicidal as it was in a place like Tombstone, Arizona Territory — was clearly on the side of town marshal Virgil Earp when he and brothers Morgan and Wyatt, along with friend John Henry “Doc” Holliday, sucker-gunned the Clanton and McLaury brothers in a back lot behind the O.K. Corral during a brief and pitiless midafternoon shooting exercise that had little to do with upholding the law.

When all was done (in about 30 seconds), three cowboy ruffians were dead, and Morgan, Virgil, and Holliday were injured to varying degrees. An unscathed Wyatt Earp would be cleared of any wrongdoing in this affair (along with his brothers and Holliday) by a court justice ally who’d ignored all neutral testimony during a post-shootout hearing.

“In any unbiased court,” writes author William Weir in Written With Lead, “the Earps and Holliday would have been found guilty of premeditated murder. But there was no unbiased court in Tombstone.” Instead, the most famous Western battle — its name popularized by the heavily fictionalized 1957 movie Gunfight at the O.K. Corral — would, as Weir writes, “become as much a part of American folklore as George Washington and the cherry tree.”

Outliving his peers and finding an eager 20th-century audience, Wyatt Earp would likewise boost his own reputation in later retellings as the West’s premier gunfighter of that era. Nevertheless, “given the fuzzy aims and tangled compromises of frontier law enforcement,” notes Earp biographer Allen Barra, “he is probably as much of a hero as we’ll ever have a right to.”

HARRY MORSE VERSUS JUAN SOTO

May 10, 1871

Saucelito Valley, California

California’s epic gun battle of the late 19th century was between just two heavies. Alameda County sheriff Harry Morse — a tireless outlaw hunter — and his elusive white whale, a gargantuan cross-eyed beast of a bandito named Juan Soto.

A tip that Soto was hiding out in the Saucelito Valley, high in the Coast Range of Central California near Hollister, had led Morse and a group of lawmen to a clearing of adobes. Splitting up, Morse entered one of them with a posse member named Theodore Winchell and unexpectedly found Soto himself lounging at a table with some women and compadres. Out came Morse’s Smith & Wesson. Manos arriba!

“What followed was a spectacular one-on-one gunfight for the ages fought with pistols and rifles at close range,” says John Boessenecker, author of Lawman: The Life and Times of Harry Morse, 1835 – 1912.

Soto didn’t budge; he just sat there menacingly. Morse ordered Winchell to cuff the burly outlaw. When Winchell lost his nerve, fleeing out the door in terror and leaving Morse short-handed, two of Soto’s goons grabbed the sheriff while Soto leaped to his feet and struggled to draw his pistols. Somehow Morse managed to get out of the adobe without being shot by the enraged Soto, pursuing with his six-shooter in hand.

Outside, Morse miraculously dodged several bullets from Soto, now armed with three five-shooters, during a theatrical battle that continually had Morse’s men believing their partner was hit. Ultimately, Morse would prevail with a 100-plus-yard killing shot to Soto’s head, cementing his reputation, notes Boessenecker, “as the best known peace officer and manhunter on the Pacific Coast.”

FRISCO SHOOTOUT

October 1884

Frisco Plaza, New Mexico

Armed with a pair of six-shooters, a mail-order sheriff’s badge, and some steel nerves, a bold 19-year-old New Mexican named Elfego Baca took it upon himself to arrest a drunken cowboy named Charlie McCarty who was busy shooting at the feet of Mexican citizens in the small town of Frisco Plaza (now Reserve) — to “make them dance.”

When McCarty’s foreman, joined by a passel of punchers, demanded McCarty’s release, Baca gave them “three seconds” to go away and then began firing, killing the foreman and leading an 80-man mob of cowboys to return the next morning.

Baca took cover in a tiny hut; hunkering on a recessed mud floor, he got some shots off while weathering an assault that allegedly sprayed the hut with 4,000 bullets (367 in the door alone). After a 33-hour siege, four cowboy assailants would be dead and Baca very much alive, calmly cooking breakfast in the back. Or so the story goes.

The siege ended with Baca’s negotiated surrender under sheriff supervision. He faced a pair of murder trials, won two acquittals, and went on to a long, prosperous life as an attorney, school superintendent, and politician.

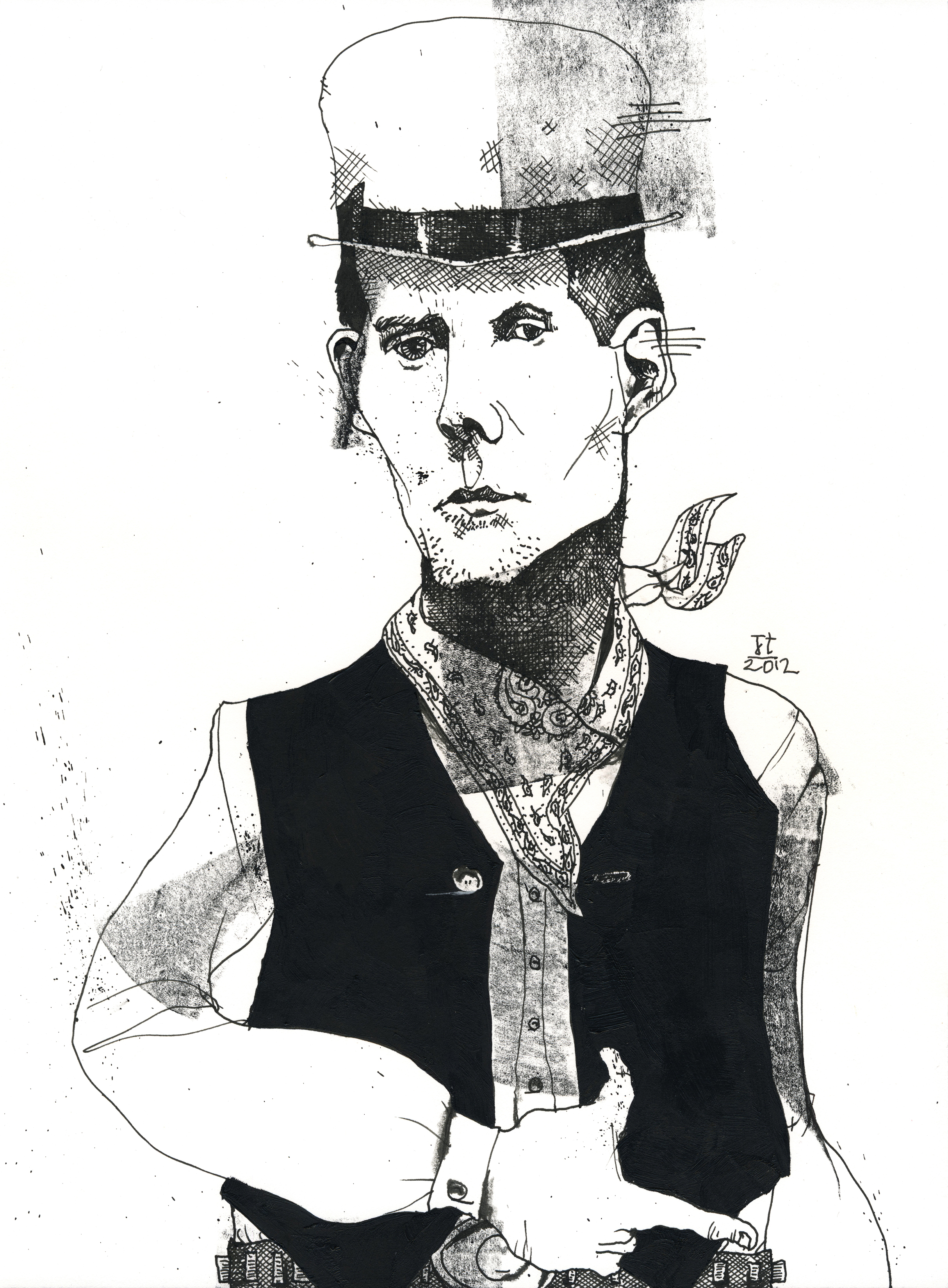

LUKE SHORT VERSUS “LONGHAIR JIM” COURTRIGHT

February 8, 1887

Fort Worth, Texas

An easy nominee for “Last Great Duel of the Old West,” this clash between two prize gunfighters was sparked by a fairly mundane dispute over gambling hall kickbacks.

The players: Luke Short, a dapper gambler and saloonkeeper who’d once dealt for the house at the Oriental Saloon in Tombstone and recently had sold his stake in Fort Worth’s White Elephant Saloon; and Timothy Isaiah “Longhair Jim” Courtright, an ex-Fort Worth marshal who was back in Cowtown running a “detective agency” that was little more than an extortion operation.

When Courtright approached Short about protection money for the White Elephant, Short told him where to go.

“That’s when people started talking about something brewing between these two guys,” says Doug Harman, Western historian with the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame. “If any gunfight had a certain High Noon-style anticipation to it, it was this one.”

On the fateful night, a drunken Courtright entered town and called out Short. The two men stood face-to-face at close range outside the White Elephant. In one of the more well-documented but hard-to-believe draws, Short took off Courtright’s thumb on his first shot. Unable to cock his pistol, Courtright “border shifted” to his other hand too late. Short had already planted two bullets in his chest.

The duel’s aftermath wasn’t short on irony, notes Harman. “The building Courtright fell against when he died was a target practice spot called the Shooting Gallery. And to this day, the two men are buried just a few feet apart in Fort Worth’s Oakwood Cemetery.”

KC RANCH STANDOFF

April 8, 1892

Johnson County, Wyoming

A valiant standoff at the remote KC Ranch by local homesteader Nate Champion against a large band of hired gunmen was the epic, if peripheral, gun battle of Wyoming’s Johnson County War — a messy, highly symbolic engagement between small farmers and wealthy ranchers that would ultimately involve U.S. Cavalry intervention at the main TA Ranch siege site near the town of Buffalo.

“All the other fatalities in the Johnson County War were ambushes — just outright assassinations,” says Bill O’Neal, author of The Johnson County War. “But Nate Champion, who was high up on the cattle barons’ ‘rustler’ hit list, managed to hold off some 50-odd invaders for an entire day while cornered in a tiny cabin with a dying friend, a six-gun, and a Winchester.”

During a frigid night, a group of hired guns and ranch foremen for the powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association had surrounded Champion’s cabin, capturing two innocent trappers on the property and picking off Champion’s partner Nick Ray, who’d ventured outside the following morning to look for them. Dragging a fatally shot Ray back inside the cabin, Champion staved off a murderous siege for hours while nursing his dying friend, jotting notes in a later-retrieved diary, and enabling time for the alarm and a counterattack posse to be raised in Buffalo.

The invaders knew enough to give Champion a wide berth, O’Neal adds. “He’d already been attacked by about half a dozen stock detectives out to get him the previous November. They’d busted into his cabin and he single-handedly fended them off with one gun. That was the beginning of his legend.”

And KC was the end. Forced to attempt an escape later that afternoon when the cabin was set afire, Champion bolted for a nearby ravine and ran straight into mortal enemy fire. The cabin is long gone, but the town of Kaycee remains a testament to Wyoming’s most famous holdout. So does Champion’s lasting sobriquet: “the bravest man in Johnson County.”

From the November/December 2013 issue.