After spending his youth reading and re-reading The Journals of Lewis and Clark, Francis Parkman’s The Oregon Trail, and John C. Frémont’s tales of Western exploration, 17-year-old James Willard Schultz boarded a flat-bottomed steamboat in St. Louis. Twenty-six hundred miles along the Missouri River later, having passed rolling green hills and sandstone cliffs, great herds of bison swimming in the river and bighorn sheep standing sentry on the buttes, elk and deer and grazing bands of antelope, and countless American Indian encampments along the shore, he would arrive at the boat’s final destination in Fort Benton, Montana. His life’s adventure was just beginning.

“Ours was the first boat to arrive at Fort Benton that spring. Long before we came in sight of the place, the inhabitants had seen the smoke of our craft and made preparations to receive us. When we turned the bend and neared the levee, cannon boomed, flags waved, and the entire population assembled on the shore to greet us. Foremost in the throng were the two traders who had sometime before bought out the American Fur Company, fort and all. They wore suits of blue broadcloth, their long-tailed, high-collared coats bright with brass buttons; they wore white shirts and stocks, and black cravats; their long hair, neatly combed, hung down to their shoulders. Beside them were their skilled employees — clerks, tailor, carpenter — and they wore suits of black fustian, also brass-buttoned, and their hair was likewise long, and they wore parfleche-soled moccasins, gay with intricate and flowery designs of cut beads. Behind these prominent personages the group was most picturesque; here were the French employees, mostly creoles from St. Louis and the lower Mississippi, men who had passed their lives in the employ of the American Fur Company, and had cordelled many a boat up the vast distances of the winding Missouri. These men wore the black fustian capotes, or hooded coats, fustian or buckskin trousers held in place by a bright-hued sash. Then there were bull-whackers, and mule-skinners, and independent traders and trappers, most of them attired in suits of plain or fringed and beaded buckskin, and nearly all of them had knives and Colt’s powder and ball six-shooters stuck in their belts; and their headgear, especially that of the traders and trappers, was homemade, being generally the skin of a kit fox roughly sewn in circular form, head in front and tail hanging down behind. Back of the whites were a number of Indians, men and youths from a nearby camp, and women married to the resident and visiting whites. I had already learned from what I had seen of the various tribes on our way up the river, that the everyday Indian of the plains is not the gorgeously attired, eagle-plume-bedecked creature various prints and written descriptions had led me to believe he was. Of course, all of them possessed such fancy attire, but it was worn only on state occasions. Those I now saw wore blanket or cow (buffalo) leather leggings, plain or beaded moccasins, calico shirts, and either blanket or cow-leather toga. Most of them were bareheaded, their hair neatly braided, and their faces were painted with reddish-brown ochre or Chinese vermilion. Some carried a bow and quiver of arrows; some had flintlock fukes, a few of the more modern cap-lock rifle. The women wore dresses of calico; a few ‘wives’ of the traders and clerks and skilled laborers even wore silk, and gold chains and watches, and all had the inevitable gorgeously hued and fringed shawl thrown over their shoulders.

“At one glance the eye could take in the whole town, as it was at that time. There was the great rectangular adobe fort, with bastions mounting cannon at each corner. A short distance above it were a few cabins, built of logs or adobe. Back of these, scattered out in the long, wide flat-bottom, was camp after camp of trader and trapper, string after string of canvas-covered freighters’ wagons, and down at the lower end of the flat were several hundred lodges of Piegans. All this motley crowd had been assembling for days and weeks, impatiently awaiting the arrival of the steamboats. The supply of provisions and things brought up by the boats the previous year had fallen far short of the demand. There was no tobacco to be had at any price. Keno Bill, who ran a saloon and gambling house, was the only one who had any liquor, and that was alcohol diluted with water, four to one. He sold it for a dollar a drink. There was no flour, no sugar, no bacon in the town, but that did not matter, for there was plenty of buffalo and antelope meat. What all craved, Indians and whites, was the fragrant weed and the flowing bowl. And here it was, a whole steamboat load, together with a certain amount of groceries; no wonder cannon boomed and flags waved, and the population cheered when the boat hove in sight.”

— Excerpted from My Life as an Indian by James Willard Schultz (Doubleday, Page, & Co., 1907)

It is easy to imagine the excitement of 17-year-old James Willard Schultz as the steamboat pulled away from the docks in St. Louis on a warm April morning in 1877. The free-spirited child of a staid New England family, he had recently ended his junior year at military school by firing the campus cannon and shattering many windows. Lean and lively, he loved to hunt and roam outdoors, and from an early age he had yearned for big adventures in the Far West.

Now he was heading up the Missouri River to Fort Benton in the Montana Territory. He had letters of introduction to the fur traders at the fort, a Henry rifle for hunting buffalo, and, luckily for us, a good supply of notebooks and ink. Later in life, when he began writing books about his experiences, the details recorded in those journals would be invaluable.

Schultz is best known for his first book, an enduring classic of frontier literature called My Life as an Indian. It opens with a colorful account of the steamboat journey and his arrival at Fort Benton. The inhabitants had run out of flour, bacon, sugar, and tobacco over the winter, and they were nearly out of liquor. Knowing that the steamboat was heavily laden with all these commodities and more, they celebrated its approach with loud cheers, flag-waving, and booming explosions from the fort’s cannons.

As soon as the steamboat was unloaded, the Piegan Blackfeet started trading their buffalo hides and wolf pelts for whiskey, tobacco, knives, guns, powder, blankets, Chinese vermilion, and other goods. Young Schultz must have been confident and likeable, because that evening, as drunken warriors charged up and down on their ponies, recklessly shooting their guns, he made a good impression on two older traders. Joseph Kipp, given the pseudonym “Berry” in My Life as an Indian, invited him to a traders’ and trappers’ ball at a cabin outside the fort. Schultz danced the quadrille with a Piegan woman, and later that night he struck up a friendship with her husband — a white trader known as Sorrel Horse who lived in a tepee and spoke fluent Blackfeet.

Sorrel Horse was heading out onto the plains with a band of Piegans for the summer bison hunt, and he invited Schultz to come along. It was the kind of invitation Schultz had dreamed of in giddy moments back in Boonville, New York, and he accepted at once. That summer he learned the thrill of galloping into a herd of running bison and shooting from the saddle, knowing at any moment that his horse could stumble in a badger hole and send him flying toward a certain death under the trampling hooves. He picked up the sign language of the Plains, and made swift progress in the difficult Blackfeet language. He helped his best friend Wolverine steal the girl he loved from a camp of Gros Ventres.

Schultz had promised his mother he would come home and resume his studies. Instead, he spent just three months in New York before returning to Montana. By the following winter, he was holed up at Fort Conrad on the Marias River with Kipp and 3,500 Piegans camped a short distance away.

As Schultz immersed himself deeper into the Blackfeet way of life, he began talking at length with medicine men and older warriors, recording tribal customs, beliefs, religious ceremonies, and oral traditions. The three tribes of the Blackfoot Confederacy — the Piegans, Bloods (or Kainai), and Blackfeet proper — dominated the northern Montana and southern Alberta plains. Now they were back making war on their traditional enemies: Crows, Crees, Assiniboines, Sioux.

Scholars warn that Schultz can be an unreliable source. He was not a trained ethnographer but a storyteller who didn’t let inconvenient facts get in the way of a rollicking good yarn. He’s vague and contradictory with dates and locations. He introduces elements of fiction into his memoirs. That being said, according to his biographer Warren L. Hanna, he’s dependable and accurate when describing the beliefs and lifeways of the Blackfeet because, instead of portraying cultural stereotypes, he was largely writing about his own good friends.

When he describes a horse-stealing raid on a Cree war party, he’s able to give us several different perspectives, including his own, because he was right there in the thick of things shooting at the enemy. Schultz stays a little vague about his record in tribal warfare, but the Blackfeet credited him with two kills, making him eligible to marry.

When the time came, after pressure from his friends to take a Piegan wife, no courtship or marriage ceremony was involved. He simply inquired after a 16-year-old girl who caught his eye: “good-looking, fairly tall, and well-formed, and she had fine large, candid, expressive eyes, perfect white, even teeth and heavy braided hair which hung almost to the ground.”

Normally a prospective husband would have to give horses to the bride’s father as a dowry, sometimes 50 or more, but in Schultz’s case this fee was waived. He merely had to promise her mother that he would be good to her. She quietly moved into his tepee and started tidying up and washing his clothes, signaling that she was now his wife without actually speaking a word.

Her name was Mutsi-Awotan-Ahki, or Fine Shield Woman. Schultz would come to call her Nätahki, an affectionate nickname meaning “cute or pretty girl.” The Blackfeet name that Schultz used proudly for the rest of his life was Apikuni, which he usually translated as Spotted Robe. Marriages between white men and Indian women were common in the fur trade, but they were often marriages of temporary convenience for the men. Apikuni and Nätahki, however, became deeply devoted to each other, and My Life as an Indian is, in large part, a cross-cultural love story, at least from Schultz’s perspective.

The couple moved to several trading posts as Schultz partnered up with Kipp to trade with the Blackfeet for their robes. They went through a time of shattering change together, as the buffalo disappeared from the plains and the Blackfeet way of life became impossible. White hide hunters wiped out most of the buffalo, but the notion that Indians only took what they needed and used every part of the animal was not true during most of the 19th century. The Blackfeet and other Plains tribes were killing more buffalo than they needed in order to trade the hides for whiskey, rifles, cloth, kettles, and other manufactured goods.

When the Blackfeet were corralled onto their reservation near Browning, Montana, hunger and starvation ensued, mainly because ineffective and sometimes corrupt government agents were unsuccessful in securing adequate food supplies. This is when Schultz began his long career as an advocate, letter writer, and fundraiser for the Blackfeet and other tribes. He and Nätahki lived in a cabin on the reservation, became cattle ranchers, and raised a son, Lone Wolf. He grew up to be a wild young cowboy, and then a nationally renowned artist.

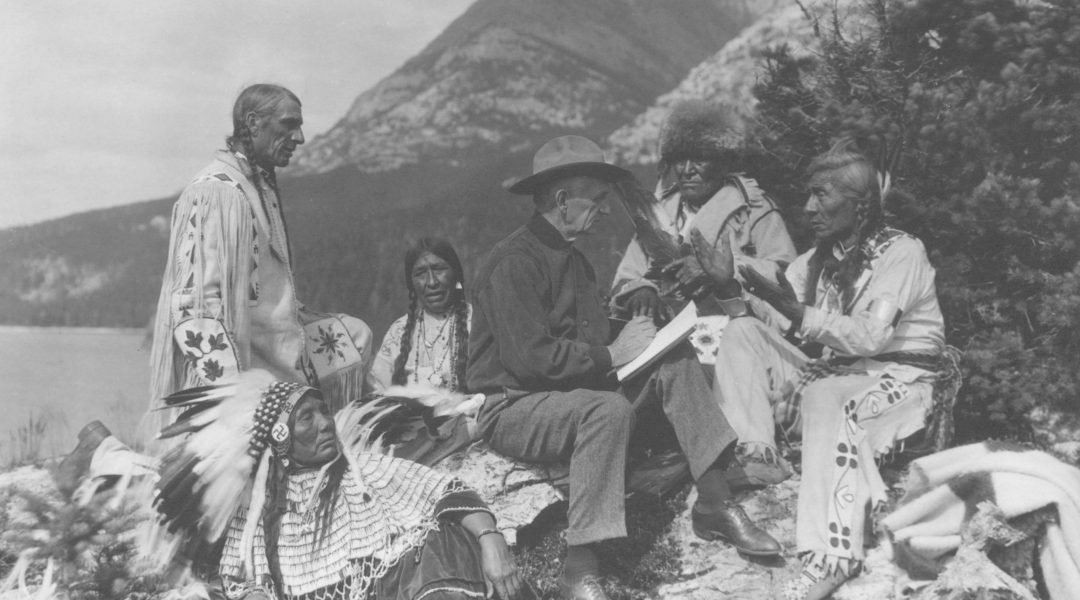

If you look at a map of Glacier National Park, you will see Apikuni Falls, Apikuni Mountain, and Natahki Lake. Schultz started hunting and fishing in the St. Mary Lakes country in 1883 and worked for 18 years as a part-time guide in the future national park. One of his regular clients and close friends was George Bird Grinnell, the anthropologist, conservationist, and editor of Forest and Stream magazine, which had started publishing regular articles by Schultz about hunting and Blackfeet. Grinnell was instrumental in getting the national park established in 1910, and several landforms are named after him.

The biggest tragedy in Schultz’s life was the death of Nätahki in 1902, apparently from a heart condition. Shortly after her passing, a depressed Schultz agreed to accompany Joseph Pulitzer’s son Ralph on an ill-fated outing in the St. Mary Lakes area. Despite Schultz’s protests, Pulitzer shot four bighorn rams out of season. The deed was discovered by a game warden, who came across trophy photographs of the kill. Both Schultz and Pulitzer were arrested, and although the case would ultimately be dismissed, Schultz was warned to leave town because the warden was still seeking retribution.

He first hid out with friends around Montana but eventually fled to Seattle, where he hopped a steamer to San Francisco. There he broached the idea of writing the story of his life with Forest and Stream editor George Grinnell. After appearing in 25 installments in Grinnell’s magazine, My Life as an Indian was published to great acclaim in 1907, the same year Schultz ended up in Los Angeles and landed a job as literary editor of the Los Angeles Times.

For the rest of his life, Schultz, or Apikuni as he usually introduced himself, was a full-time writer, drawing on his memories and notebooks and living in the past. He wrote 37 books in total; most of them were colorful frontier adventure tales for boys or collections of Blackfeet lore that he gathered on summer visits to the reservation.

Lonely in Los Angeles and totally inexperienced in the ways of white courtship, he advertised for a bride and landed one named Celia Hawkins. She liked being married to a writer, but she found the subject matter of his books boring. She was a modern, urban woman and had no use for Indians. When they traveled to Montana, she would stay in a hotel by herself rather than go to the reservation to visit his old friends.

In 1927, Schultz met a young professor in Montana called Jessica Donaldson who shared his lifelong interest in the American Indian, and she became his third wife. It was a good marriage, but his later years were dominated by bad health, lack of money, and rootlessness. They lived in Bozeman, Montana; Tucson, Arizona; Berkeley, California; and then Browning, Montana, where Donaldson found work with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration during the Depression. Schultz was glad to revisit his old haunts in Glacier National Park and his dwindling group of old friends on the reservation.

In 1940, Donaldson was transferred to Fort Washakie, Wyoming, and that’s where Schultz died on June 11, 1947, as four inches of snow fell in a summer storm. He was 87 years old. He was buried at the foot of a buffalo jump on the Blackfeet Nation next to Nätahki’s mother. In New York and Chicago and San Francisco, literary critics compared him to James Fenimore Cooper.

The Piegan Blackfeet showed their respect in a way that would have pleased him more. All the full-bloods living on the reservation, without exception, made their way down the steep trail to the burying ground. Four elderly medicine men prayed for his spirit as it flew toward the Sand Hills, and a chief recounted his coups in battle. Then came the mourning song and a long wail, followed by a period of quiet reflection as the birds sang.

Schultz had requested no grave marker, but so many requests came from his readers that his son, Lone Wolf, designed a simple monument with two buffalo bulls and his father’s names in English and Blackfeet.

From the October 2015 issue.