On his 100th birthday, we remember the Western folk hero who gave America an alternative national anthem and changed music forever.

The small, scrappy tramp wandered onto the Broadway stage, his sweat-stained cowboy hat cocked back, hiding a mound of wayward hair. “Howdy,” he said, squinting into the spotlight as he stood in front of a fabricated tar paper shack. He scratched his head with a guitar pick then brought it down upon the strings of his borrowed Martin and started wailing about hard times, hard traveling, and hard working out West.

It was March 3, 1940, and the Forrest Theater was hosting a benefit concert for the John Steinbeck Committee for Agricultural Workers. Second on the bill was a man who referred to himself as “The Dustiest of the Dust Bowlers,” a 28-year-old Okie who had hitchhiked to New York just a couple of months earlier.

Standing in the wings of the stage was Alan Lomax, the assistant director of the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress. When Woody started playing, Lomax, who had dedicated his life to preserving the last traces of the country’s folk music heritage, perked up. He knew he had found something that he had come to believe only existed in legends. He was standing a few feet away from the last great American folk hero.

Charley and Nora Guthrie gave birth to Woodrow Wilson Guthrie on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma. Woody would later refer to his hometown as “one of the singingest, square dancingest, drinkingest, yellingest, preachingest, walkingest, talkingest, laughingest, cryingest, shootingest, fist fightingest, bleedingest, gamblingest, gun, club and razor carryingest of our ranch towns and farm towns, because it blossomed out into one of our first Oil Boom Towns.”

Woody would often hear his father singing spirituals and chants he had learned from his African-American and American Indian friends and neighbors, and Nora soothed the boy with songs she had learned growing up in Tennessee — Scottish and Irish ballads from her mother and grandmother, as well as the multicultural songs of the South.

“My mother was an ear musician,” Woody later wrote. “Songs meant a lot to her and she collected hundreds of them in her head, and she chorded on the piano and sung tales and stories that taught me the history of our section of the country, its weather, cyclones, pretty women, love affairs, outlaws, disasters, and hopes for the better world that’s coming.”

“By learning those songs, Woody was the far end of Elizabethan ballad tradition,” says Billy Bragg, a British musician and activist who worked with Woody’s daughter Nora to record three albums of Woody’s previously unreleased lyrics. “These were songs that made it across the ocean, came down through Appalachia, into the Plains, and ended up in the Oklahoma hills.” As eclectic as his interest grew, Woody’s music would always stay rooted in those rural tunes that survived with the same pioneering spirit as those who brought them to America.

Young Woody soaked it all up and found even more musical inspiration as soon as he started roaming around town. Boomers and roughnecks flocked to the former Creek Indian settlement seeking their fortune, and Woody’s appetite for their far-flung melodies and regional lyrics was insatiable. “He grew up in the boomtown era when people were coming through and singing on the streets, looking for change and trying to entertain each other in the saloons,” says Arlo Guthrie, Woody’s son and fellow folk musician. “He wandered around and just fell in love with the idea that he could play music.”

He saw music as a “hoping machine” that got him through hard times, and because of Charley’s inability to keep a job and Nora’s mental deterioration due to Huntington’s disease, he needed it plenty. There were mysterious incidents linked to Nora’s erratic behavior, but it wasn’t until Charley woke up from a nap one day to find himself covered in flames, his wife standing over him, that Nora was taken away to the state mental hospital where she would spend the rest of her life.

Woody kept his mother’s spirit alive by learning how to play the guitar and singing her old ballads. He eventually started playing well enough to form the Corncob Trio and joined a local cowboy band. The dream then was simple: make music and have a good time. “When you see a photo of Woody in the cowboy band, they’re in their chaps and hats, you see a photo like that and you realize, this is a man who was bent on having some fun,” Arlo says. “He wasn’t making political points; he just wanted to party.”

The young musician was settling in nicely, but he was never comfortable with the idea of staying in one place. As his talent developed, he started to see music as a new kind of hope — a ticket out of Okie territory. The perfect excuse to leave came on April 14, 1935, when a dark wall of dust reaching to the sky engulfed the town, burying fields and homes in a thick cloak of dirt.

Heading out to California, he began to become the character of Woody Guthrie as we know it,” Bragg says. “He invented that corn pone Okie persona, which I think he picked up a lot from Will Rogers, who was one of his heroes.”

But the West Coast wasn’t exactly the Eden Woody had expected. “He gets to California and there’s this anti-intra-America immigration movement,” says Mark Allan Jackson, author of Prophet Singer: The Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie. “His people aren’t being welcomed. There are signs saying ‘No Okies allowed,’ and police are treating certain people differently because of their accent or the way they dress. And when you see that, you’re forced into a sense of political perspective to some degree.”

After the mythos of the American dream dissipated into dust for hundreds of thousands of hardworking farmers and laborers, many in the working class came to view communism as the new Americanism and a logical response to a system that had left them without homes and jobs. “When you go from living off the fat of the land and then you’re shoved into a Godforsaken fruit picker’s lifestyle, nothing looks right,” says country music artist and Woody devotee Marty Stuart. “And you have to lash out and you have to report and you have to come back when there’s no hope. All bets are off.” Woody never joined a political party, but when asked about his political affiliations, he’d always say, “I ain’t a communist necessarily, but I been in the red all my life.”

As he traveled around California, playing live on the radio at the same stations being visited by the Carter Family, he met migrants and talked to them about their misery and anger.

“That’s when he starts to realize that music had another thing going for it,” Arlo says. “It could make people feel good at a time when they were feeling really bad. It could cleanse your soul. And he decided that was the kind of music that he wanted to start making — music that said, we might actually come out of this alive; we can survive if we do things together.”

On the radio, Woody started hearing the Carter Family sing “I Can’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore,” a commercialized, poppy country tune that, in his mind, told people to grin and bear the bad times and wait for heaven. Frustrated with the unfair treatment of his fellow Okies and disgusted by the bastardization of the music he was raised on, Woody wrote an alternative version of the song titled “I Ain’t Got No Home.” The song was more than just a heartbreaking tale of the Dust Bowl refugee’s blues. It was a rallying cry.

By the time Woody finally made his way to the Atlantic, East Coasters didn’t know what to make of this strange man from the West. “Woody blows into New York City in 1940, and there are all these college guys from the East writing political songs and labor songs,” Bragg says. “They’ve never even seen a dust storm. And then this guy turns up out of the Dust Bowl who is the real McCoy, and he’s got these brilliant songs that just blow you away. And on the way to New York he was inspired to write a song that would become one of the most iconic songs in American history.”

As Woody hitchhiked up North, he kept hearing Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” on all the jukeboxes, but it didn’t represent the America he had experienced. So Woody created his own version of the song titled “This Land Is Your Land.”

“One part is a celebration of the beauty of America, but the other part is a denunciation of the economic restrictions that other people suffered under,” says Woody biographer Jackson. “He’s saying this is a more realistic vision of America. It’s not a song putting us down. Sure, he pointed out the wrongs, but that should be a part of the American spirit.”

Woody’s song combined both praise and protest and set them to a simple, catchy tune. Of course, the modern school-book version excludes the verses of anger and rebellion. “And this is the point, in New York, where he completes his transition from a balladeer, singing songs traced back to Elizabethan days, into the first modern alternative musician,” Bragg says.

When he finally made it onto his first major stage in New York, the night of the Steinbeck fundraiser, the still little-known vagrant from the West entranced everyone in the theater. But two young men backstage were particularly moved: Lomax and a songwriter by the name of Pete Seeger, who was trying desperately to hide his upper-class upbringing so that he could be taken seriously in the folk scene.

“Pete Seeger once told me that Woody was like a correspondent that rode a boxcar through the world, and when he looked and saw things that needed talking about and telling about, he wrote about it and sung about it,” Stuart says.

Seeger saw a hero, but Lomax saw a national treasure. “Lomax was looking for someone who could authentically represent the Anglo ballad tradition,” Jackson says. “And Woody comes on stage and he’s doing his Will Rogers routine, telling jokes and stories and launching into song with his accent. Lomax saw this real nature that was a representation of a large hunk of

Americans — not just Okies, but the South and the Southwest.”

As soon as Woody finished his set, Lomax sought out the boxcar correspondent and invited Woody to Washington, D.C., to record for the Library of Congress archives, then later had him perform on his radio program and convinced RCA-Victor Records to produce Woody’s first album, Dust Bowl Ballads.

Once again, Woody was settling in nicely, and once again he missed his rambling ways. So he packed up his family and headed back to California in January 1941, explaining to Lomax in a letter, “I ruther to raise my kids like a herd of young antelope out here in the fresh air. Maybe that’s wrong, but that’s the way I feel about it. Everything around here is good and clean and fresh and natural and if you aint got a bag of money in the big city it’s a lowdown rotten joint to get caught in.”

Woody only spent six months out West before hitching a ride back to New York on a cattle car. Seeger had formed a folk supergroup, the Almanac Singers, and Woody was eager to get in on the fun. He met the love of his life, Marjorie Mazia, a dancer in the Martha Graham Dance Company, and they moved to a house on Mermaid Avenue in Coney Island. They would have four children together, but the next decade would prove to be a tumultuous one. Woody began to have wild fits, and his usual charming rambles would often deteriorate into unintelligible rhymey slurs.

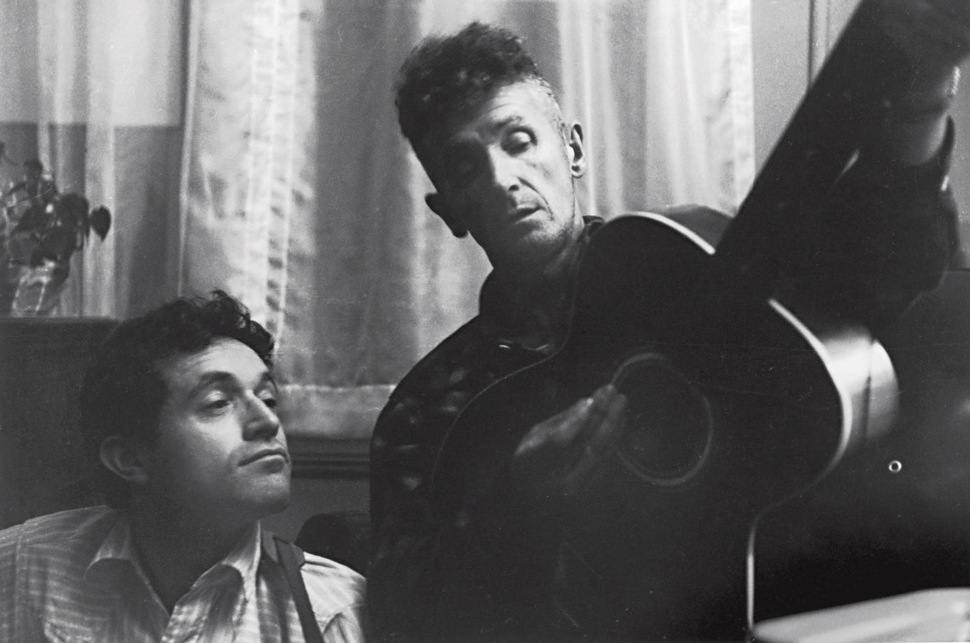

By then a new generation of musicians had made their way to the New York folk scene. One young singer carried a guitar, wore a cowboy hat, and went by the stage name Buck Elliott, later changing it to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Elliott had done some rodeoing in his day, and the only hero he regarded higher than any cowboy was Woody Guthrie.

Elliott wasn’t the only tenderfoot to visit Woody, but he was the first to catch his attention — because his impression of Woody was flawless. Elliott moved in with the Guthries and joined Woody on his last ramble across America. When Elliott talks about those memories now, at the age of 80, he relishes the moments, pausing with youthful chuckles. “He was my hero; I was his sidekick,” Elliott says before growing somber. “It was painful for me. When I first met him he was already beginning to develop some of the symptoms of Huntington’s disease. He was acting strange. His arm would fly up in the air and hit him on the side of the head uncontrollably, repeatedly, six or seven times. He was starting to get dizzy spells. Of course, it didn’t help that we’d start drinking whiskey at 5 in the morning.”

The children Woody had with Marjorie shared even fewer good times with their father. “The memories that stand out are sad ones,” says Nora. “Our relationship was completely that of caretaking — doing his laundry, helping him eat, holding his hand as he walked, lighting his cigarette. It overwhelmed anything else. All of my dad’s friends were telling me, ‘Man, he wrote some great songs.’ But for a 10-year-old, a 5-year-old, you just think, Oh my God, this is tough.”

In his moments of clarity he would try to enjoy being a father, taking his kids to the beach or playing music for them. He never seemed to care much about being anything more than a father and he never let on that his music was known across the country. “The only song he ever sat me down to play was ‘This Land Is Your Land,’ ” Arlo says. “And it was only because I asked him to. I went to school one morning and all the kids were singing that song and I didn’t know the words because I didn’t realize my dad’s stuff was famous outside of the house. So I went home and I was really embarrassed and I asked him to show me how to play it on my three-quarter-size Gibson guitar he’d given me. He made sure I knew those three extra verses you won’t find in the schoolbooks. I went back the next day. I went back armed.”

As Woody withered away in a hospital bed, his canonization began. His songs and stories spread across the country. Many of the musicians who gathered around Washington Square fabricated their own tales of a rambling past and tried to mimic Woody’s style and voice.

“People finally started to see that Woody Guthrie is one of the greatest American folk heroes that we have,” Stuart says. “His writings, his drawings, and especially his songs are among the most profound ever written by anybody in any genre, any culture. Woody needs to be in the Country Music Hall of Fame. He needs to be in the Blues Hall of Fame. Fortunately, he’s already in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He needs to be in every hall of fame that exists. Because we’re all a part of Woody’s DNA. We wouldn’t have had a Hank Williams or Merle Haggard or Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen if it wasn’t for what Woody Guthrie did.”

After Woody died on October 3, 1967, his family decided to spread his ashes at his favorite spot. They marched out onto one of the rock jetties projecting from Coney Island, punctured the canister with a beer-can opener, and cast the dust into the Atlantic.

“He loved that area. It was so different from where he came from out on the plains of Oklahoma,” Arlo says. “He loved being on the edge of things, right on the land that meets the sea that meets the sky. After we said our final farewell, we walked over to Nathan’s Famous and celebrated Dad’s life with hot dogs and root beers.”

From the July 2012 issue.