The Texas town of Crawford is about as far from Washington, D.C., as a man could hope to get.

By now the stories of over- indulgence are yesterday’s news. When the longest and strongest bull market in the history of the United States peaked in the late 1990s, the number of newly minted millionaires and billionaires seemed unending—as did their excesses. Gulfstreams replaced Hummers as the ride of choice, $20,000 dinners became cocktail party fodder, and the concept of a second home was upgraded to include third, fourth, and fifth locations.

But in 1999 when Governor George W. Bush gave architect David Heymann a list of design priorities for the new ranch house that he and his wife sought to build, the Texan’s top three requests were anything but extravagant: a king-sized bed, a good shower, and some comfortable chairs on the porch.

The ranch retreat is a presidential tradition that dates back long before Camp David. Ronald Reagan’s Rancho del Cielo and LBJ’s Pedernales spread are only the most recent incarnations of a Western connection to the White House that began with Teddy Roosevelt. It was 1883 when a 24-year-old TR first set foot in Little Missouri, a soon-to-be-forgotten cowtown in the Dakota Territory. Intent on overcoming his physical frailties, Roosevelt spent two weeks in the region on his first foray. By the time he left, he had bagged not only a bison but also a stake in the Maltese Cross Ranch.

It was the first of two cattle operations the Knickerbocker would buy into, and the years he spent ranching, hunting, and scouting the “Bad Lands” would serve him well up San Juan Hill and into the White House. In Roosevelt’s words, “The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom.”

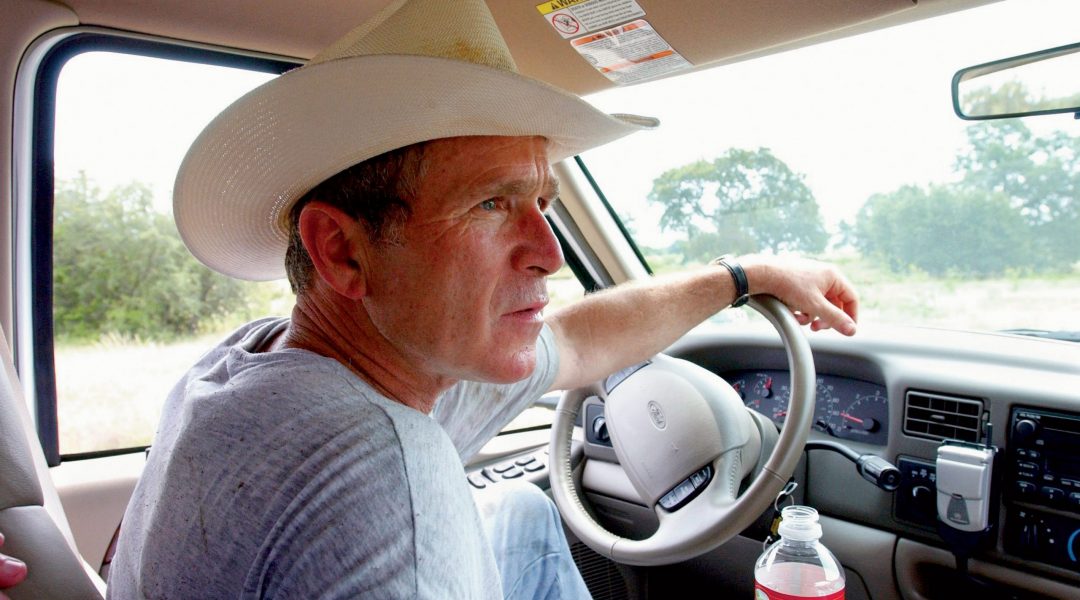

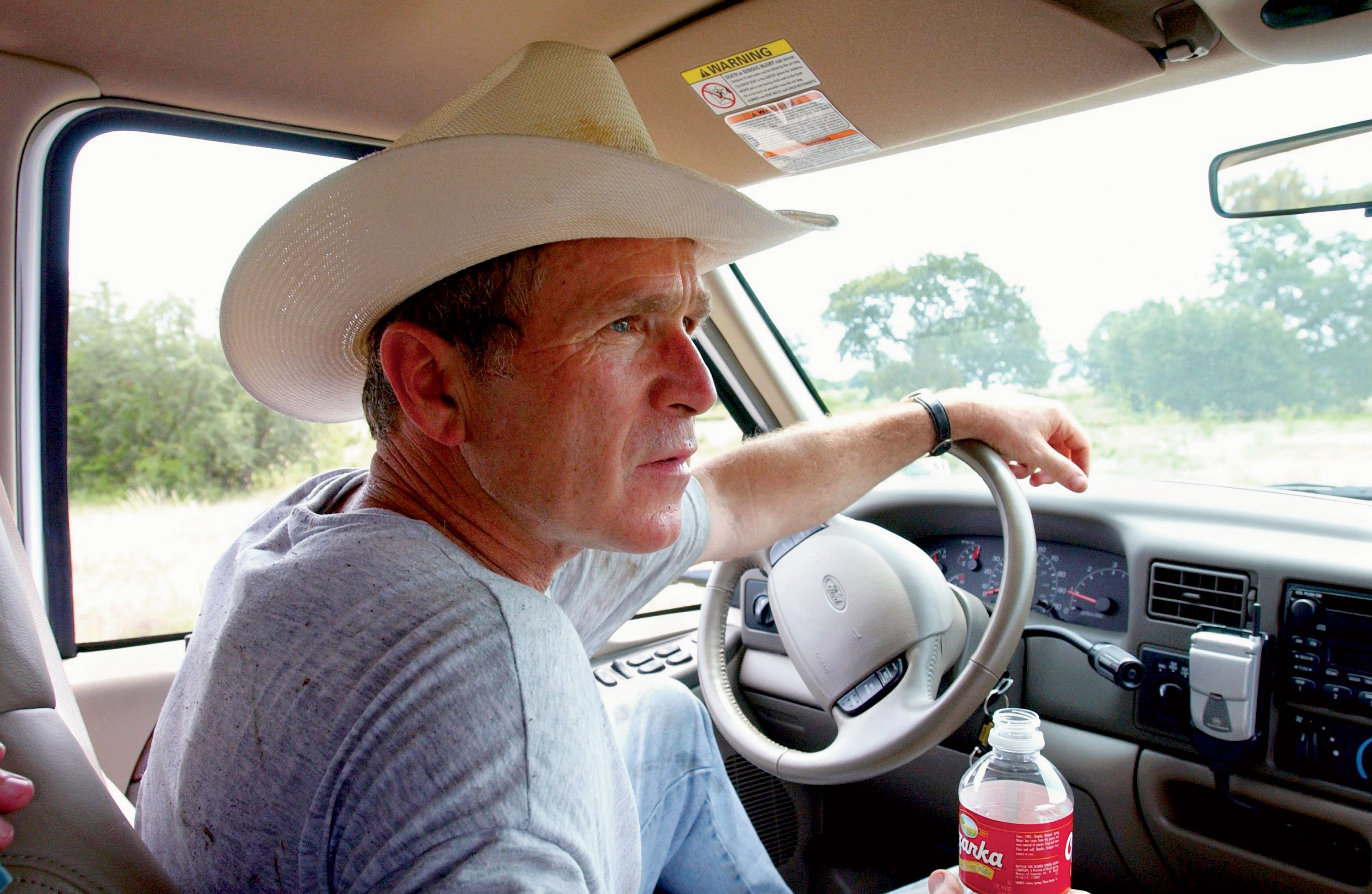

A century later, one of Roosevelt’s successors finds similar solace in the Lone Star State among the live oaks and limestone canyons of McLennan County. The Bushes’ now-traditional August hiatus on their ranch outside Crawford is as much an attempt at normalcy as it is a working vacation with visits by foreign dignitaries and heads of state, regular gatherings with White House staffers and Cabinet members, and some good, old-fashioned politicking.

“I want to stay in touch with real Americans,” said President Bush to a crowd of Crawford residents shortly after the 2001 inaugural ceremonies. As the locals knew, the President and the First Lady had already put those plans in motion several years earlier by purchasing a spread in the heart of “real America” during his second term as governor of Texas. Flush with a $14.9-million profit from the sale of the Texas Rangers in 1998, the couple had set out in search of a retreat within easy driving distance of the Governor’s Mansion in Austin. When the Bushes came across a 1,550-acre tract 20 miles west of Waco just outside the town of Crawford (population 701), they took a second look.

For more than a century much of the land along this stretch of Prairie Chapel Road had been owned by members of a pioneering German family, the Engelbrechts. This particular parcel belonged to Bennie and Earlene Engelbrecht. The couple was getting well on in years and had listed the property for sale for almost four years. It took less than four months for the Bushes to close the deal, for an estim-ated $1.3 million.

Well watered by Rainey Creek and the Middle Bosque River, much of the ranch features the gently rolling terrain that makes this section of Central Texas ideal for farming wheat, maize, and corn. One of the Bushes’ first decisions as owners was to continue to run cattle on their ranch; the grass lease was awarded to none other than Kenneth Engelbrecht, Bennie and Earlene’s son.

A more momentous undertaking—the design and construction of a new home for the Bushes—would begin during George Walker Bush’s gubernatorial tenure and be completed only after his presidential inauguration. Their choice of Austin architect David Heymann revealed a commitment to build a house that fit naturally into the landscape.

“The Bushes told me they had this beautiful piece of land and they wanted the house to add to the land, not disrupt it,” says Heymann, an associate dean of architecture at the University of Texas. “Given the complexity of their lives, they wanted a place where they could feel grounded. They wanted to be in the land and related to it.”

To this end, Heymann traveled to Crawford with the couple and spent much time siting the residence and designing the layout.

According to Heymann, the four-bedroom home was planned so that “every room has a relationship with something in the landscape that’s different from the room next door. Each of the rooms feels like a slightly different place.”

The resulting single-story ranch house, which was built by members of a religious community from the nearby community of Elm Mott, is a paragon of environmental planning.

The passive-solar house is built of honey-colored native limestone and positioned to absorb winter sunlight, warming the interior walkways and walls of the 4,000-square-foot residence. Geothermal heat pumps circulate water through pipes buried 300 feet deep in the ground. These waters pass through a heat exchange system that keeps the home warm in winter and cool in summer.

A 25,000-gallon underground cistern collects rainwater gathered from roof urns; wastewater from sinks, toilets, and showers cascades into underground purifying tanks and is also funneled into the cistern. The water from the cistern is then used to irrigate the landscaping around the four-bedroom home. Laura Bush insisted on the use of indigenous grasses, shrubs, and flowers to complete the exterior treatment of the home.

In addition to its minimal environmental impact, the look and layout of the new ranch house reflect one of the Bush family’s paramount priorities: relaxation. A spacious 10-foot porch wraps completely around the residence and beckons the family outdoors.

With few hallways to speak of, family and guests make their way from room to room either directly or by way of the porch. Heymann says, “The house doesn’t hold you in. Where the porch ends there is grass. There is no step-up at all.”

Although the layout and design of the Bushes’ home creates a relaxing, laid- back setting, life on the First Ranch is anything but slow-paced.

The President is a tried and true early riser—be it in Washington or on the ranch. Trips to Crawford, however, afford him liberties unavailable at the White House or even at Camp David. His daily workout is a prime example. In comparison with the monotony of the White House jogging track—a quarter-mile circuit around the South Lawn—the roads and trails on the ranch’s 1,550 acres are a runner’s paradise. Given the opportunity, the President works out six days a week. And that’s before chores.

There’s a touch of the Reaganesque to Mr. Bush’s gung-ho attitude for clearing out the dense brush thickets on the ranch, and taking the wheel of his pickup to tool around the ranch is a luxury the President of the United States rarely savors. (For reasons of security and protocol, the Secret Service chauffeurs the President and the First Lady on almost every conceivable occasion.)

Although the rigors of running the United States follow him to Crawford, the President routinely works in a round of golf on nearby links or wets a hook in one of the ranch’s man-made lakes.

As at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the Bushes relish time spent with friends and family. Gatherings at the ranch, official and otherwise, tend to be quite informal, with suit and tie replaced by short-sleeved shirts and jeans.

David Heymann credits the President with this easygoing feel. “He wanted it to be very relaxed. The way he described it, he wanted a house for people to come over, sit on the couch, and eat hamburgers and beans with their shoes off.”

The Editors wish to thank the White House Media Office for their research assistance. Portions of this article were also compiled from the archives of the Chicago Tribune, Houston Chronicle, The New York Times, Runner’s World, USA Today, and The Washington Post.

From the December 2002 issue.