Bass Reeves and Pistol Pete are just two of the many Western subjects renowned sculptor Harold “H” Holden memorialized during his award-winning career.

Harold Holden’s studio behind his home in the country outside Enid, Oklahoma, looks as if he just stepped out. His widow, Edna Mae, still visits the studio, where “H,” as he was known to family and friends, created his monumental bronze sculptures and other projects. “Afternoons or evenings I’d go out there and take him an adult beverage, and we’d sit there and listen to some cowboy music,” she says. “He occasionally would ask me to critique things, and then other times he’d ask me not to critique things. I miss all that. I miss everything about him.”

“H” was 83 when he died in December 2023. While the passage of time is not easing the pain for Edna Mae, there is some solace in the completion of the last monument H was working on when he died. Pistol Pete, a massive bronze of the official mascot of Oklahoma State University, made it to its intended home on campus last fall.

Oklahoma’s Native Son, life and one-quarter size, in front of Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Laura Flies).

Oklahoma’s Native Son, life and one-quarter size, in front of Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Laura Flies).

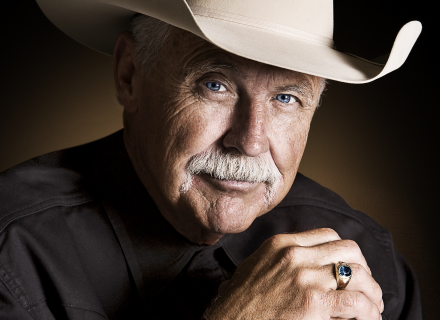

While the Pistol Pete that roams the sidelines of OSU football games is of course a caricature, there was a real Pistol Pete. Frank Eaton was a legendary Old West Oklahoma cowboy, lawman, and blacksmith, who sported a bushy mustache, wore his long hair in braids under a big custom cowboy hat, and earned his nickname for his skill with the loaded .45 Colt he carried long after the Wild West was tamed. Born in 1860, Eaton supposedly inspired the Steve McQueen Western Nevada Smith. Pistol Pete was 97 when he died in 1958, the year OSU adopted him as its mascot. H had met the legend as a child and got to sit in his lap and hold his gun. “That meeting had a real impact and left a lasting impression on that little 5-year-old boy,” Edna Mae says. “It stuck in his mind throughout his whole career.”

Cowboys and horses were natural subjects for H. “I’ve been around horses all my life,” he told me when I visited his home in 2021. Growing up in Enid, H’s father was an avid horseman and polo player, whose saddle is displayed in the Holden living room. Harold was just 6 when his dad was killed in a plane crash, leaving his mother a widow at age 31 with three young children. But grandparents stepped in to help, his mother remarried, and H blossomed, playing football, running track, and winning a boxing title at the military academy where he attended summer school.

Harold Holden’s Pistol Pete, a massive bronze of the official mascot of Oklahoma State University, was unfinished at his death in December 2023 but completed by sculptor friends and dedicated on campus last fall (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Joe Ownbey).

Harold Holden’s Pistol Pete, a massive bronze of the official mascot of Oklahoma State University, was unfinished at his death in December 2023 but completed by sculptor friends and dedicated on campus last fall (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Joe Ownbey).

All the while he was riding, raising, and drawing horses. “That’s why I wanted to be an artist,” H had said. “That was my subject matter.”

“He knew when he was young that he wanted to be an artist,” Edna Mae says. “He just didn’t think he could make a living at it.”

Holden was planning to work in the Texas oil fields when he happened to meet an instructor at the Texas Academy of Art. After graduating in 1962, he became the art director of Horseman magazine in Houston, spending evenings perfecting his own fine art and the sculpture he taught himself. “He found sculpture to be easier, because you can see everything in all of its dimensions,” Edna Mae says. “But he was also a very good painter. He did a postage stamp and a couple of big paintings in the Oklahoma State Capitol.”

The future member of the Cowboy Artists of America soon tired of the big city. A doctor back home in Oklahoma hosted what turned out to be a successful one-man show of H’s work. “It went over pretty good, and I just kept at it,” H recalled.

Keeper of the Plains on the Garfield County Courthouse lawn in Enid, Oklahoma (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Edna Mae Holden).

Keeper of the Plains on the Garfield County Courthouse lawn in Enid, Oklahoma (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Edna Mae Holden).

He completed the first of his 25 monumental sculptures in 1987. Displayed in downtown Enid, Boomer (the same subject as his 1993 postage stamp painting) is a cowboy galloping to stake an Oklahoma land rush claim. Completing it was no easy task. “I learned everything on that deal,” the soft-spoken cowboy remembered, adding with a chuckle, “and I didn’t make much money learning!”

More commissions followed: The Rancher monument for The National Ranching Heritage Center (a maquette of which is the group’s annual Golden Spur Award); a reclining buffalo that greets visitors to the Oklahoma History Center; and, Headin’ to Market, a cowboy driving cattle that graces a corner of Stockyard City in Oklahoma City. “Gradually, [I] got some customers and just kept working at it,” H said. “Didn’t get rich, but I was doing what I wanted to do.”

With Edna Mae handling the business side of things, H could focus on creating. And for 35 years, the couple led a charmed life. “It’s been such a gift for me to be married to him because of what he does,” she told C&I in 2021. “We’ve traveled all over the country, gone to great ranches, met great people. It’s been a lot of fun.”

Boomer (shown as a maquette) — completed in 1987 and installed in Enid, Oklahoma, the first of 25 monumental sculptures Holden completed — depicts the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1893 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Edna Mae Holden).

Boomer (shown as a maquette) — completed in 1987 and installed in Enid, Oklahoma, the first of 25 monumental sculptures Holden completed — depicts the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1893 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Edna Mae Holden).

It almost ended in 2010, after H was diagnosed with a terminal lung disease. He was down to 135 pounds and perhaps a week to live when the lung transplant they’d been praying for finally came through. “I was standing at the kitchen window,” Edna Mae recalls, “just praying for God to throw us a bone. Please throw us a bone. And the phone rang.”

The lung transplant was successful. Out of the hospital, H was soon back on a horse. “Went to the bar, had a few beers, and went roping,” he chuckled.

Thirteen precious years followed, priceless time with grandchildren, busy commission work, and more honors, including induction into the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Hall of Great Westerners at the Western Heritage Awards, where H received the trophy sculpture he created for that very event.

Pistol Pete was about two-thirds complete when this beloved cowboy artist ran out of time. John Rule and Paul Moore, two dear and accomplished sculptor friends, stepped in to finish the project, refusing to take a penny for their efforts. The finished monument was dedicated in September 2024 on the OSU campus. University president Dr. Kayse Marie Shrum spoke at the gathering, which included music from cowboy singer and close family friend RW Hampton. Rule and Moore were both on hand, along with members of Frank Eaton’s family, plus a number of former OSU Pistol Pete mascots.

Sculptor Harold Holden with his bronze Monarch at Rest, at the Oklahoma History Center Museum in Oklahoma City (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Mark Bedor).

Sculptor Harold Holden with his bronze Monarch at Rest, at the Oklahoma History Center Museum in Oklahoma City (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Mark Bedor).

“It was sad but really nice,” Edna Mae reflected a few days later. “The Pistol Pete monument was something he always wanted to do, so it was a perfect bookend to H’s 55- year career. It’s a beautiful sculpture, and it was a really good day. The only thing missing was H.”

From our January 2025 issue.