What was this huge reddish-colored beast that roamed the West with a devilish-looking creature on its back?

In 1883, an Arizona newspaper called the Mohave County Miner ran a story about huge and strange animals that were seen roaming through the Eagle Creek area. One of these animals was blamed for the trampling death of a rancher’s wife. This grisly incident was witnessed by another rancher’s wife, who described a “huge reddish-colored beast” with a “devilish-looking creature” riding on its back.

The monstrous animal and its equally frightful rider were sighted twice within the following week, with eyewitnesses noting that clumps of reddish hair from the animal were left from its visit. At one stop, something else was also left behind — a human skull. The eyewitnesses claimed the rider was a skeleton that was tied to the camel’s back under an elaborate web of straps, and during the journey its skull came loose and fell off.

The only known photograph of one of the camels used by Army prior to the Civil War.

The only known photograph of one of the camels used by Army prior to the Civil War.

This remarkable being was dubbed the Red Ghost, but the animal that confused the Arizona locals was soon identified by a Salt River rancher named Cyrus Hamblin, who recognized it from his youthful days in an Army cavalry regiment. It was a camel, and its presence in the Old West was one of the more curious chapters in military history. But the story behind the camel’s skeletal rider was less easily explained.

In 1853, Jefferson Davis was U.S. Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce, and during this time he faced the challenge in maintaining transportation to the forts across the western frontier. The region’s long stretches of desert proved fatal for many of the horses and mules used to transport personnel and equipment.

Enter the idea of camels.

Davis recalled a conversation he had with Maj. Henry Wayne during the Mexican War regarding how camels were used by Napoleon in his conquest of Egypt. Davis pitched the idea of camels for the Army to Congress, but two years passed before $30,000 in federal funds were allocated for the import of camels from the Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire.

Two shipments of camels were secured, one in 1855 consisting of 34 dromedary and Bactrian camels and another in 1857 with 41 more animals.

In 1856, the Army hired Hi Jolly (aka Hadji Ali), an Ottoman subject of Syrian and Greek descent, to be one of its first-ever camel drivers and head up the camel-drive experiment in the Southwest.

Whatever experience and expertise Jolly might have brought to the project, unfortunately, the Army officers in charge of the operation did not properly research what they were getting themselves into, and they soon learned that camels behaved very differently from horses and mules. They were not easily domesticated and were prone to spitting, biting, and vomiting on their handlers. There were also complaints that the camels ate much more than expected, thus increasing the budget for their maintenance.

American sailors moving a Bactrian camel on a ship for its journey across the Atlantic.

American sailors moving a Bactrian camel on a ship for its journey across the Atlantic.

However, the camels had no problems adapting to the desert terrain of the western states and they quickly proved themselves to be more efficient as beasts of burden than the horses and mules that were previously used.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, the Army shifted its focus away from the western territories and the camel brigades were scrapped. Some of the camels were sold to mining camps on the West Coast — with a few going as far north as British Columbia — but most of the animals were set free into the wilderness, where they thrived for decades. Some were captured by Confederate forces during the Civil War, but they had no use for the animals and set them free.

Most of the wild camels avoided direct contact with people, which makes the deadly encounter between the Red Ghost and the rancher’s wife highly unusual. That animal became the subject of occasional eyewitness sightings for the next 10 years, until a farmer named Mizoo Hastings fatally shot the camel while it was eating in his yard on the Arizonan frontier.

The camel’s body did not contain its skeleton rider, although it was wrapped in leather straps that were applied so tightly that its flesh was scarred. The people who examined the dead camel insisted it was impossible for a person to tie himself to the camel, which raised the question of why a man was bound to a camel’s back and doomed to such a strange death.

The Mohave County Miner also covered the camel’s demise and opined the unlucky rider could have been “an ugly piece of humor of somebody who had a camel and a corpse for which he had no use.”

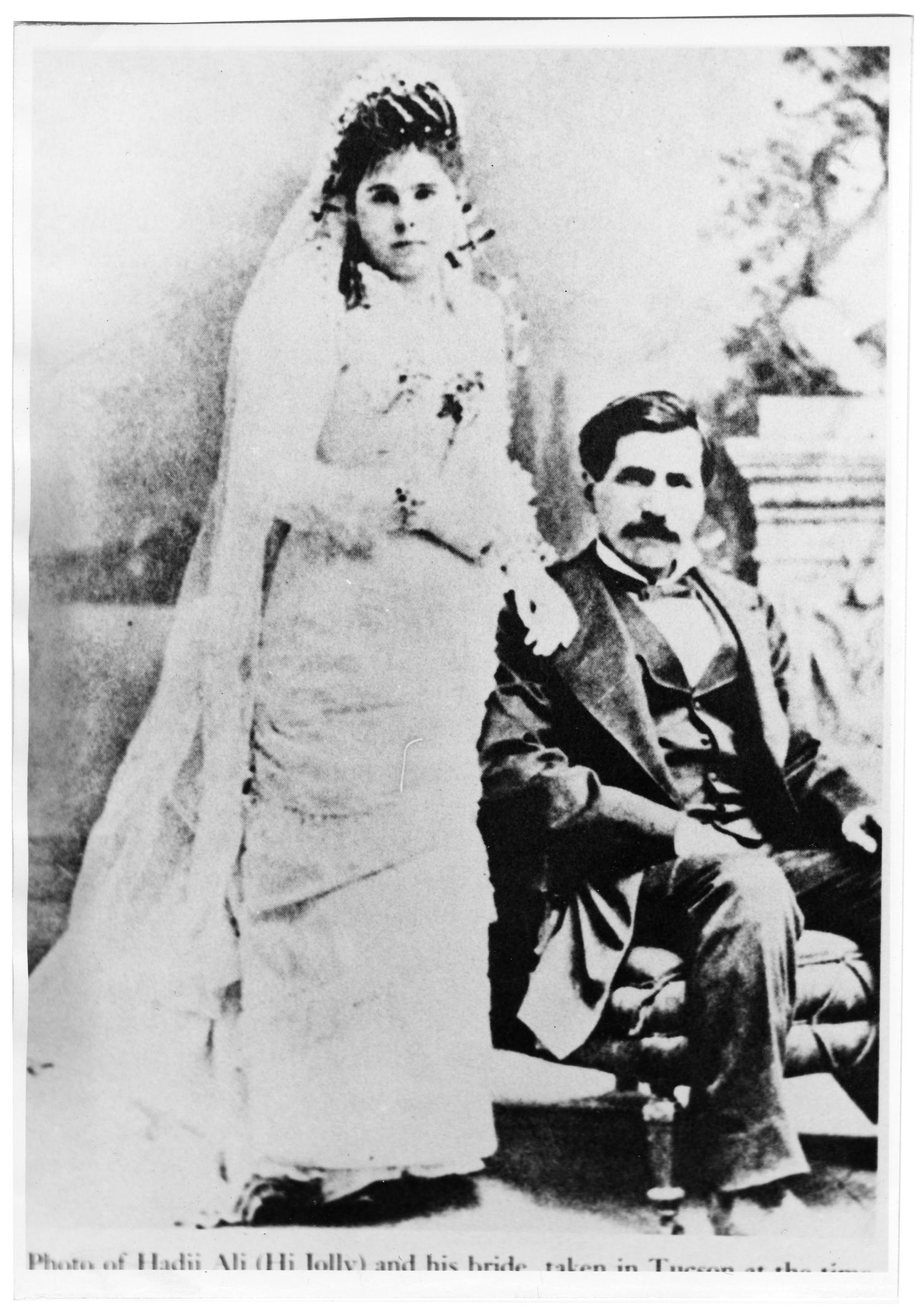

Hadii Ali (Hi Jolly) with his bride in Tucson, Arizona.

Hadii Ali (Hi Jolly) with his bride in Tucson, Arizona.

Some historians have insisted the story of the Red Ghost was a tall tale, adding that the newspapers of the era often blurred exaggerated accounts among their genuine reporting. Independent verification of this story beyond the Mohave County Miner is nonexistent.

Still, sightings of the original imported camels and their domestic-bred descendants continued long after the Red Ghost’s reign of terror was mostly forgotten. The last known wild camel in the American wilderness was seen in West Texas in 1941, a lonely and distant figure far removed from its aggressive Red Ghost cousin who supposedly terrorized Old Arizona.

The spirit of the Red Ghost still inhabits the folklore and landscape of the area. A sculpture of the doomed camel stand in Quartzite, Arizona, not far from the grave of Hi Jolly.

Read more of our Spooky Western stories.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the National Archives