Cheyenne and Arapaho warrior artists incarcerated at Fort Marion, Florida, are remembered in an exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

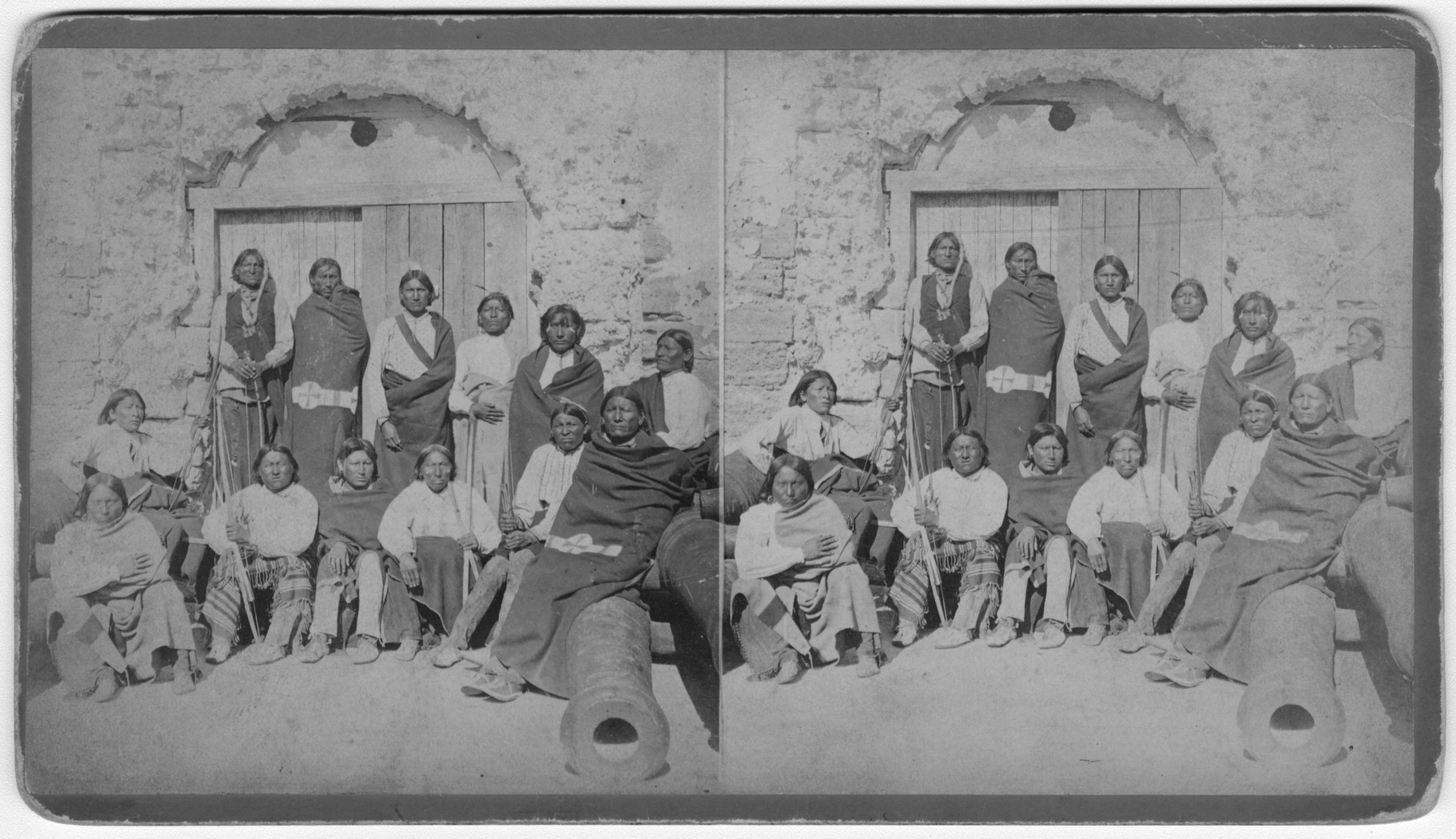

When the Civil War ended and the country shifted from North-South warfare to East-West migration, new fronts opened up. There were tensions over land and resources between Native Americans, miners, and European immigrant settlers. Among other hostilities, this friction culminated in the Red River War of 1874. In that military campaign, the Army displaced tribes from the Southern Plains and forcibly relocated them to reservations in Indian Territory. In the aftermath, the government ordered the arrest of 72 Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Caddo, and Arapaho warriors. Of these, 15 were Cheyenne; they, like the others, were taken from their families, put on trains, and sent on a monthlong journey to St. Augustine, Florida, where they would be imprisoned for the next three years at Fort Marion.

Soon after the warriors arrived at Fort Marion, government agents, wanting to instill discipline, cut their long hair, issued them military uniforms, and contained them in a foreign environment they could hardly understand and adjust to — stories that have been documented by historians and government agents for over a century. In the new exhibition Cheyenne Ledger Art From Fort Marion, opening September 2024 at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, the Cheyenne and Arapaho get to tell their own story — one that highlights the journey east, as well as the life they left behind.

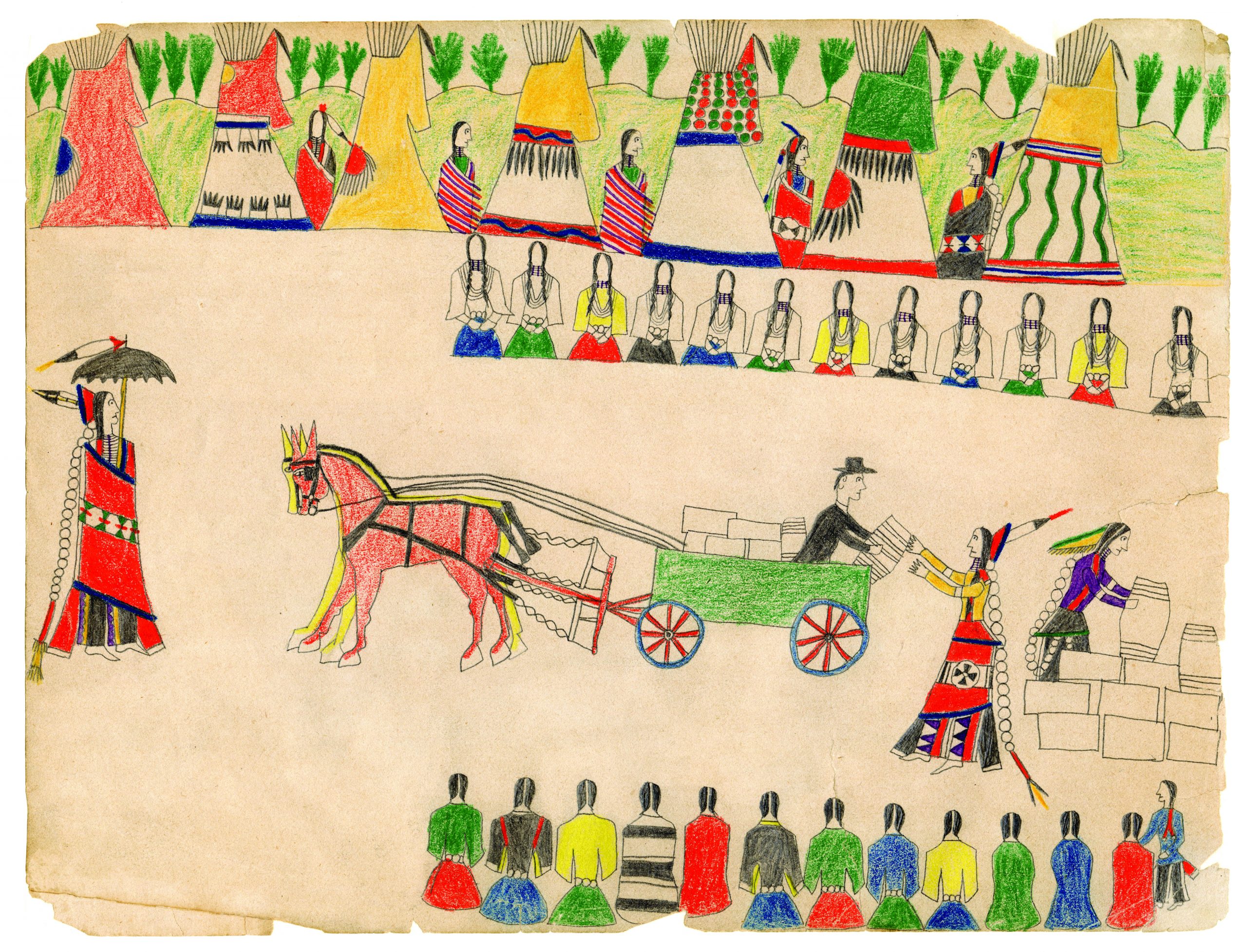

Distributing Annuities, by Bear’s Heart, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, paper on pencil. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1997.07.010.

Distributing Annuities, by Bear’s Heart, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, paper on pencil. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1997.07.010.

It’s a story told in art.

“The Fort Marion ledger artists and the drawings they produced during their imprisonment in Florida have a continuing impact because this is where ledger art began a new creative and artistic style of documenting actual historical accounts of Cheyenne and Arapaho history, their incarceration at the fort, and significant events that took place during their journey to Florida. It was also a traumatic transitional period of freedom as a warrior to incarcerated prisoner of war,” says Dr. Eric Singleton, curator of Native American Art and Ethnology at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and co-curator of the exhibition. “Over time, these warriors saw an economic opportunity in selling their artwork, as well as bows, arrows, ceramic vases, fans, and sea beans to tourists, Euro-American high society people from the Northeast, and religious faith-based teachers. The money they made was used to purchase clothing and other items in town. It was also sent home to their impoverished families. The Fort Marion ledger art continues today to be researched, studied, and interpreted by historians and scholars.”

In that spirit, Singleton worked in collaboration with co-curator Gordon Yellowman, Tribal Historian for the Culture Resource program at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, to tell the story of the Fort Marion Cheyenne warrior artists from the perspective of the art they created. C&I spoke with Yellowman about the art, the men, and the importance of sharing their stories.

Traditionally clothed prominent Cheyenne chiefs and warriors at Fort Marion, 1875.

Traditionally clothed prominent Cheyenne chiefs and warriors at Fort Marion, 1875.

Cowboys & Indians: How did you come to know Eric Singleton and get involved with the Cheyenne ledger art exhibition?

Gordon Yellowman: Eric and I started working on the project in 2019 or 2020 when the curator at the Cummer Museum, Jacksonville, Florida, called Eric and asked if there were any exhibits or artworks in the Silberman Collection that were easily accessible for a loan. We started working on identifying people and material culture objects in the Cheyenne ledger drawings and we sent the idea of an exhibition to the Cummer Museum, and they loved it. Since we were already talking about doing a Cheyenne ledger art exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, it just worked out. Since then, the Cummer Museum exhibit traveled to the Old Town Jail Center in Albany, Texas. This exhibition took it a step further with additional material culture items and more contemporary art works and descendant interviews. Eric and I look at those earlier exhibitions as stepping stones to an expanded and more in-depth Cheyenne ledger art exhibit, which we are doing.

C&I: The exhibition includes four Cheyenne warrior-artists — Making Medicine, Bear’s Heart, Squint Eyes, and Howling Wolf — and has 52 Fort Marion drawings. When you talk about “translating” their art, what do you mean?

Yellowman: I interpret the actions that appear in the ledger art drawings. My interpretations come from a Cheyenne perspective, me being a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes and also a contemporary post-reservation Cheyenne ledger artist myself. I see courting scenes, hunting scenes, warfare scenes, society rituals, dances, and journey records. I see things in the ledger drawing images, based on Cheyenne culture and history, traditions, values, and customs. For example, the name glyphs of the artist, which identify who the ledger artist is. I see and interpret symbols within the ledger artworks that only the Cheyenne would see or be able to translate. I see the Cheyenne warrior society regalia. I see expressions of love interests in courting scenes. I see loneliness in scenes of past home places or families of the warrior prisoners. I see colors that represent certain things on clothing, warrior society clothing, and women.

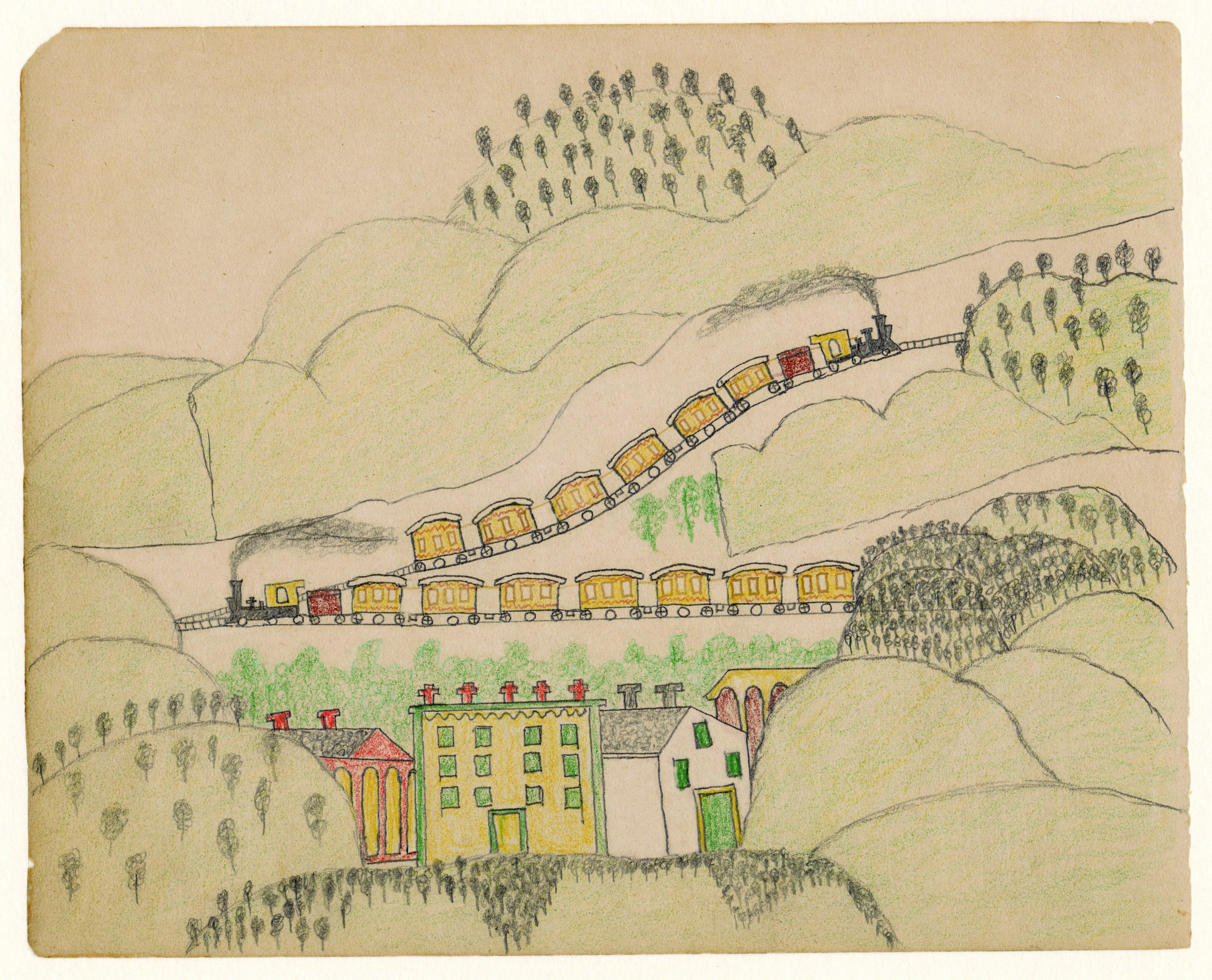

Two Trains Passing Through a Town, by Making Medicine, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, paper on pencil. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1996.27.0538.

Two Trains Passing Through a Town, by Making Medicine, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, paper on pencil. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1996.27.0538.

C&I: The exhibition focuses on the Cheyenne experience at Fort Marion. What was the Cheyenne experience?

Yellowman: The Cheyenne experience, communication, not being able to understand English, when they only spoke Cheyenne. The ledger drawings are their voices of communication, telling their story of wrongful conviction, wrongfully identified as hostile warriors, assumed they committed crimes against the whites. How they were shackled, taken away from freedom, taken away from families they loved.

C&I: As a Native American man generations removed from the incarceration at Fort Marion, what do you feel seeing the art they created?

Yellowman: I feel humbled. I feel pride and respect for the drawings created and for them providing a record of actual Cheyenne historical accounts. ... I would like people to know about the educational opportunities that Capt. [Richard Henry] Pratt provided to the Cheyenne warriors and other tribes incarcerated. The economic opportunities, selling and trading of ledger artworks for mercantile items to send back home to their families. The experience of geographical regions, the heat, the humidity, and the environment.

C&I: When the Cheyenne speak of Fort Marion, how is that history told and what is its legacy?

Yellowman: Oral histories have been handed down from one generation to another. Each story is family-oriented, and the story belongs to them. They recall a place where their relatives were imprisoned, and some died there never returning home. They recall the journey of their relatives being taking away from their families to a place unknown to them; the families thought they would never see them again or see them return home. The government singled out each warrior and misidentified some of them as hostiles (those who brought harm or death among the whites); and the government, during war time, exiled the Cheyenne warriors to prison incarceration for punishment of crimes supposedly committed. The U.S. Government took freedom from the warrior artist — freedom that wasn’t theirs to take. ...

It’s important to preserve the ledger drawings, for educational purposes for future generations to see, share, and educate themselves on the Cheyenne history recorded in the ledger drawings. Although the warriors were not confined in jail cells with the standard iron bars, they were confined to a fort. They were allowed to roam among one another and learned military drills/formations for organization and representation. They went from traditional clothing to military-style uniforms; their hair was cut, which broke the ceremonial custom of men’s hair-braiding. This exhibition is an educational experience of art history and the Cheyenne way of life. I hope it will create much-needed dialogue on recognizing a right to heal historical trauma.

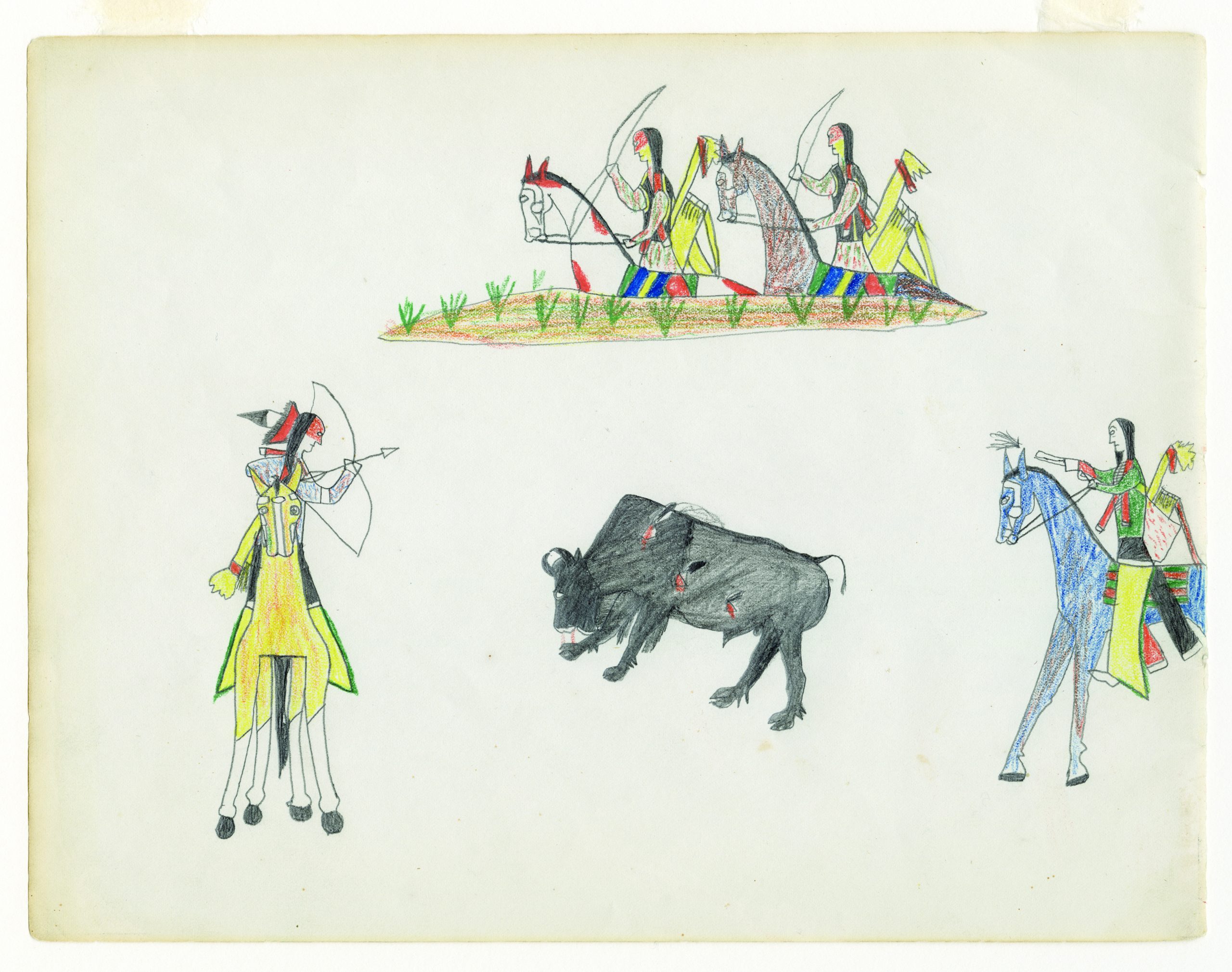

Buffalo Hunt, by Squint Eyes, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, pencil on paper. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1996.17.0141.

Buffalo Hunt, by Squint Eyes, Cheyenne, 1875 – 1878, pencil on paper. The Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1996.17.0141.

Cheyenne Ledger Art From Fort Marion is on view September 13, 2024, through January 5, 2025, at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. For more information, visit nationalcowboymuseum.org.

From our August/September 2024 issue.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum