A jet-setting photographer leaves the bright lights of the big city for the Marfa ghost lights and creates a home base that celebrates both the minimalist landscape and more-is-more décor.

Douglas Friedman was always destined to live a big life — the jet-setting photographer just happens to do it from a small West Texas town (population 1,750) located about 200 miles from the closest major airport. Granted, the town is Marfa, the high-desert home of the famed ghost lights, a Prada installation that’s become a must-snap for every single Instagram influencer, and a cavalcade of respected artists such as sculptor and painter Donald Judd, plein-air painter Rackstraw Downes, and digital drawer Jeff Elrod.

For Friedman, coming home to the middle of nowhere has become a much-needed respite after crisscrossing the world. “I’m always sad to leave and so excited to come back,” he says. “Marfa is what you make of it — you can be totally solitary or a total party monster. I’m a proud Texan now, and I love the way the town is always evolving and changing.”

Moving to the Lone Star State was never part of the plan. Friedman grew up on New York City’s Upper West Side in the 1980s. As a college freshman, he went west and studied anthropology and documentary filmmaking at Occidental College. Post-graduation he stayed in L.A. to work for director David Fincher on high-profile films like Se7en, Fight Club, and The Game. “It was amazing, but after two and a half or three years, I realized I’d never be able to make anything that amazing on my own,” he says.

Rather than settle for less, he sold everything and headed way east — the Far East — taking pictures as he backpacked through India and climbed the Himalayas. “When I came back, I needed work. An ex of mine got me a job as a photographer’s assistant, and I realized I could actually build a career and earn a good living doing this,” he says. “I gave myself four years to apprentice and tried to learn everything I could about shooting high fashion, catalogs, interiors — you name it.”

All the hard work paid off. Friedman became a top fashion photographer before pivoting his focus to shooting interiors for noted designers and swanky shelter magazines, including Elle Décor, Architectural Digest, and Veranda. “I guess you could say I fell into photography after falling out of other things,” he says. “All I knew [was] I was never going to be a lawyer, much to my parents’ disappointment. But ultimately, photography chose me.”

The same could be said about Marfa. The first time Friedman visited, he couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about. “We were there from Sunday to Tuesday, and everything was closed. It was somehow raining, humid, and hot, all at the same time,” he says. Still, he couldn’t quite shake thoughts of West Texas — in part because it was such a hot topic on the East Coast. “I went to Martha Stewart’s birthday party, and she was talking about how much she loved Marfa, and then all the other guests joined in,” he says. “I decided it was a sign.”

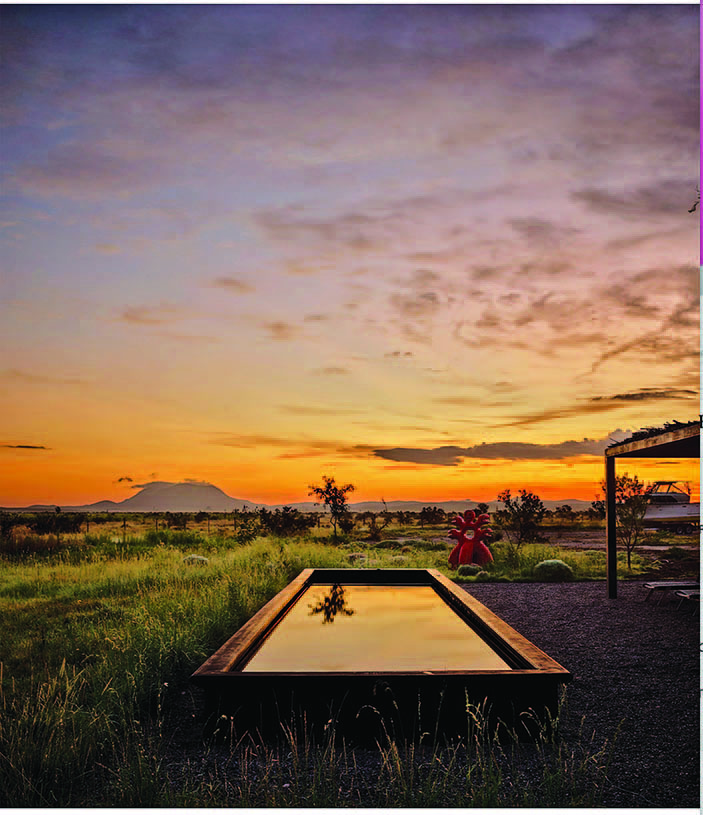

After some Googling, Friedman launched an IRL search for land. “I spent the day with my beautiful real estate broker, Mary Farley, but I wasn’t seeing anything that I was falling in love with, and I wanted to fall in love,” he says. Farley attempted a Hail Mary on a drive a mile outside of town. “We passed a double-wide trailer on blocks, a few derelict cars, a goat farm, and some rodeo cowboys. Then the road just ended on this incredible property overlooking endless grasslands and mountains,” Friedman says. “That was it.”

A few days later, the photographer had an accepted offer and a modest plan for a residence on his personal plot. “Originally, it was going to be a trailer. I was researching Airstreams, and I imagined something very Raising Arizona. But even for that, I needed infrastructure — water, power, sewage. That kind of investment warranted something more substantial,” he says.

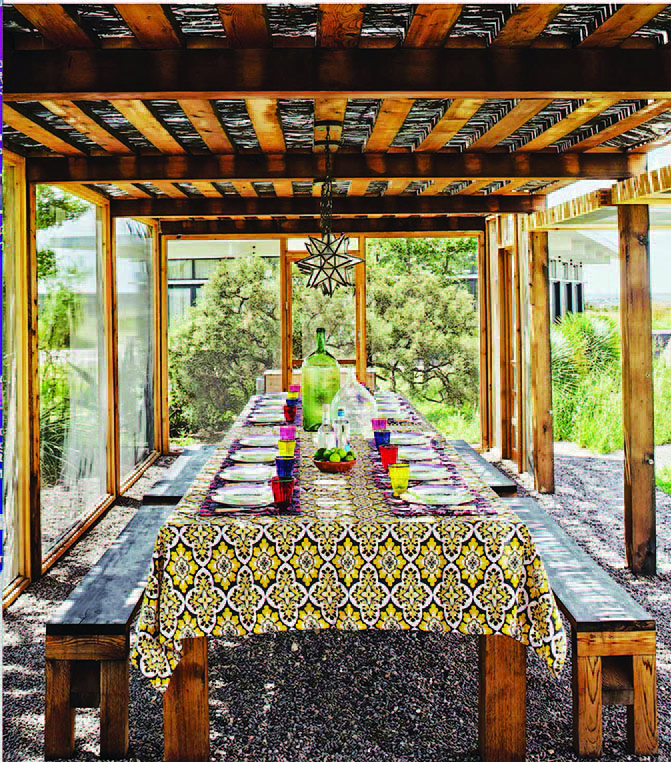

Because Friedman wanted something super symmetrical, low-maintenance, sturdy, and not-at-all-precious, the solution turned out to be a state-of-the-art modular system. After working with a New York City-based architect, he made his specifications and awaited delivery of loads of glulam timbers, steel connectors, and structural insulated panels. Then he waited patiently while contractor Billy Marginot led the charge to assemble them all onsite.

Every wall is glass. It’s definitely the type of house where you wake up with the sunrise. The open floorplan really encourages a sense of community and encourages you to be present with the people in the house.

In addition to all the laminated timber and heavy metals, there were plenty of glass deliveries as well. “Every wall is glass. It’s definitely the type of house where you wake up with the sunrise,” explains Friedman. “The open floorplan really encourages a sense of community and encourages you to be present with the people in the house.”

When it came time to furnish the approximately 2,000-square-foot, three-bedroom, two-bathroom house, Friedman leaned into a Donald Judd-inspired minimalism for both aesthetic and financial reasons. “After I built the house, I had no money, so it was all so random. There were mattresses on paletts and door-made coffee tables, but it was all I had to work with,” he says. But as he began refilling his coffers, an affinity for maximizing returned. “I thought it would be interesting to be a minimalist, but I didn’t survive it.

To create a more-is-more showplace, Friedman relied on his years of experience photographing the homes of the rich and famous, his relationships with magazine editors, and his personal Rolodex of interior designer friends like Ken Fulk, Brigette Romanek, and Steven Gambrel. He asked questions, begged for advice, and began layering in a mix of fun finds sourced locally, in New York, and via The Future Perfect. He worked with Vipp to design and install a kitchen “that doesn’t feel like a kitchen.” He even hung de Gournay wallpaper in the guest room. “It’s my homage to Liz Taylor in Giant,” he notes.

Friedman also began building an art collection composed of works produced in Marfa, by Marfa artists, or with some other connection to Marfa. “I worked closely with the curators at Ballroom Marfa and Jenny Moore, formerly of the Chinati Foundation, advised me on pieces, too,” he says. “I don’t know a lot, so it was very important to rely heavily on my friends to get my collection going.”

While Friedman says he made mistakes along the way, he knows he nailed the home’s most important asset: the views. “No matter where you are, whether you’re surrounded by these incredibly special and commanding things like de Gournay wallpaper and Kyle Bunting rugs, nothing detracts from the views,” he says. “It was an accident, but it totally worked out.”

The Friedman Ranch is available for occasional rental via airbnb.com. See Douglas Friedman’s celebrated photography work at douglasfriedman.net.

From our April 2024 issue.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Douglas Friedman