The Oscar-winning filmmaker talks about his challenging subject matter, casting Lily Gladstone, and reuniting with Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro.

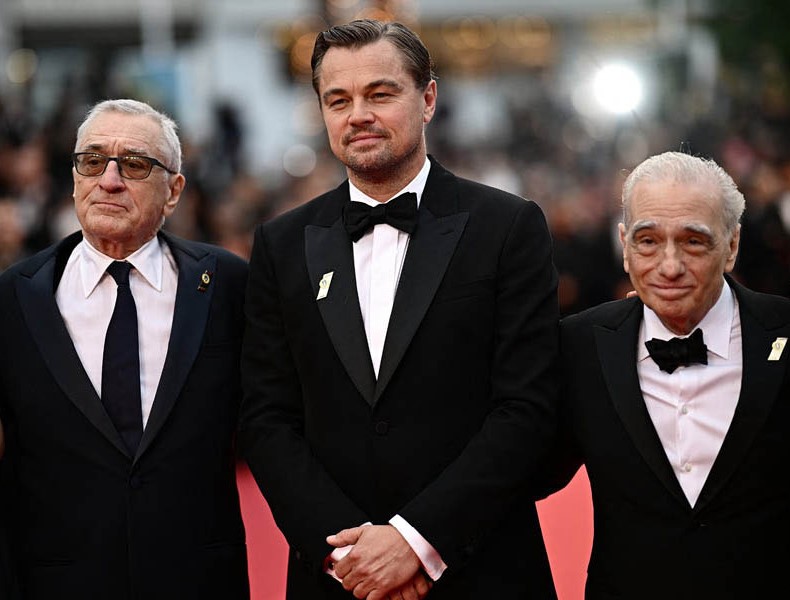

Given the ongoing actors’ strike, it has fallen on living-legend director Martin Scorsese to shoulder most of the promotional chores for Killers of the Flower Moon, his critically hailed true-life drama starring Leonard DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Lily Gladstone, ever since the movie premiered last spring at the Cannes Film Festival. But there are just so many hours in the day, and so many interview requests the 80-year-old filmmaker can fulfill. Which is why, earlier this week, Apple Original Films hosted an online “virtual press conference” designed to enable critics and journalists the opportunity to actually see and hear Scorsese discuss Killers of the Flower Moon in real time — even if only a handful of questions, submitted in advance, could be addressed.

In our current issue, you can read more about the tragic events that inspired David Grann’s 2017 nonfiction best-seller Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and The Birth of the FBI, which in turn inspired Scorsese and co-scriptwriter Eric Roth (Forrest Gump, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button). The film adaptation, which opens Friday in wide release on IMAX and conventional screens, is at once faithful to its source material and expansive in its overview as it depicts the notorious “Reign of Terror” that targeted newly oil-rich Osage Native Americans in 1920s Oklahoma. DiCaprio plays Ernest Burkhart, the catastrophically pliant nephew of William Hale (De Niro), a ruthless cattleman who involves his nephew in a land-grabbing scheme that would eventually claim dozens of Osage victims. Among the endangered: Burkhardt’s wife Mollie (Gladstone), an Osage woman who has inherited an oil fortune.

What follows are highlights culled from Scorsese’s comments during the press conference, edited for brevity and clarity.

Meeting the challenge of telling a true story

I had had an experience in the seventies where I began to become aware of the nature of what [Native Americans’] situation was, and is still is. I had been blindly unaware of that. I was too young; I was in my twenties. I didn’t know. And it’s taken me years, because I’m fascinated by the question of how do you really deal with that culture in a way that is respectful? But also not hagiographic. It doesn't fall into depicting, I think, the noble native, that sort of thing. None of that. But how truthful can we be and still have authenticity and respect, and deal with the truth, honestly, as best we can? When I read David Grann’s book, it indicated to me that this would probably be the way that we could deal with the subject. Particularly by getting involved with the culture of the Osage, and actually placing cultural elements, rituals, spiritual moments [in the film].

So, ultimately, what happened was that, at first, we were dealing with the script based on the Grann book, which is excellent. But the book also has the subtitle The Birth of the FBI. And for about a year and a half to two years, while I was doing The Irishman and that sort of thing, [screenwriter] Eric Roth and I were working. And we felt that we took the story of the birth of the FBI as far as we could take it. I wanted to keep balancing that story with the story of the Osage. And it was getting bigger and bigger and more diffused.

Ultimately, we went out to Oklahoma and met with the Osage. My first meeting was with Chief Standing Bear and his group, and it was very different than what I expected. They were naturally cautious. I had to explain to them that I’m going to try and deal with them as honestly and truthfully as possible. We weren’t going to fall into the trap of using clichés like the drunken Indian or the Indians as victims, that sort of thing, and tell the story as straight as possible.

What I didn’t really understand during the first couple of meetings was that this is an ongoing situation, an ongoing story out in Oklahoma. In other words, these are things that really weren’t talked about in the generation I was talking to. It was the generation before them that this happened to. And so they didn’t talk about it much. The people involved are still there, meaning their families are still there, the descendants are still there. And I learned a lot from meeting with them, having dinners with them.

Margie Burkhart, a relative of Ernest Burkhart, pointed out, and a number of other people pointed out, that you have to understand a lot of the white guys there, a lot of the European Americans, particularly Bill Hale — they were good friends [with Osage People]. One guy pointed out: “Henry Roan was his best friend," yet he killed him. And people just didn't believe at the time that Bill would be capable of such things. And so what is that about us as human beings that allows us to be so compartmentalized? Margie said: “One has to remember that Ernest,” her ancestor, “loved Molly and Molly loved Ernest.” It’s a love story.

So what ultimately happened is that the script shifted that way. And that’s when Leo decided to play Ernest instead of Tom White [the FBI agent portrayed in the film by Jesse Plemons]. And by that point, we started reworking the script. And it became really, instead of coming from the outside in, coming in and finding out who’d done it — in reality, it’s who didn’t do it. It’s a story of complicity. It’s a story of sin by omission, silent complicity in certain cases. And so that’s what afforded us the opportunity to open the picture up, and start from the inside out.

Casting Lily Gladstone

I believe I first saw her in Certain Women, Kelly Reichardt’s film, and I thought she was terrific. But then COVID hit and we weren’t able to meet. So after the pandemic was calming down, we met on Zoom. And I was very, very impressed by her presence — the intelligence and the emotion that’s there in her face. You see it. You feel it. You know that it’s all working, something working behind the eyes. You can see it happening. Also, her activism, which wasn’t overtaking the art. In other words, the art was in the activism in a sense. So the art takes over in a way which we think would be more resonant later on, after you see the movie. You may be thinking about it more than a person preaching at you.

I think the first big scene we did was one of my favorite scenes, where she has dinner with Ernest alone and she’s questioning him. It’s a little bit of an interrogation: “What are you doing here? What's your religion?” All this sort of thing. And then you begin to see there the connection between the two. And when she says, “Ha, ha, ha! Coyote wants money,” surprisingly, he says, “That’s right. I love money.” So this is the other thing — she knows what she’s getting into. That’s the way the script was ultimately created by these moments.

And then there’s the scene where he’s driving her in the taxi, and it's only one shot. And he says something about, “I want to see who’s going to be in this horse race.” And she answers in Osage. He goes, “What’d you say?” And she says something in Osage again. And he says, “Well, I don't know what that was, but it must’ve been Indian for ‘handsome devil.’” That’s an improv, and you see her laugh for real. So that moment you have the actual relationship, it’s actually between the two actors. So these were the two moments we felt very comfortable with her.

Also, we had a feeling that we needed her. We needed her to help us tell the story of the women there. We would always check with her and work with her on the script. There were scenes that were added, scenes that were rewritten constantly.

Working With Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio

Robert De Niro and I were teenagers together, and he’s the only one who really knows where I come from, the people I knew and that sort of thing. Some of them are still alive. He knows them. I know his friends, his old friends, and we had a real testing ground in the seventies where we tried everything and we found that we trusted each other. It was all about trust and love. It’s what it is. And that’s a big deal because very often if an actor has a lot of power — and he had a lot of power at that time — an actor could take over your picture. Studio gets angry with you, then the actor comes in and takes it over. With him, I never felt that. I never felt that. There was a freedom. There was experimenting — and also not afraid of anything. He wasn’t afraid to do something. He just did it.

And years later, Bob told me he worked with this kid, Leo DiCaprio, in This Boy’s Life, and he said, “You should work with this kid sometime.” It was just casual. But with him, something like that, a recommendation at that time, in the early ‘90s, was not casual. He says it casually, but he rarely gives recommendations. And so years go by, and I’m presented with Leo, and we worked together on Gangs of New York. He made Gangs possible, actually. He loved the pictures I made, and he wanted to explore the same territory.

And so we developed more of a relationship when we did The Aviator. And towards the end of it, there was a kind of something happening in maturity with him, I’m not quite sure. But we really clicked in certain scenes, and that led to The Departed, and then we became much closer. And so during that time, I really found out that, even though there’s decades of age difference, we have similar sensibilities. He’ll come to me and he’ll say, “Hey, listen to this record. It’s Louis Jordan and Ella Fitzgerald.” I grew up with it. He’s not bringing me anything new, but he likes it. That's interesting. Like, he’ll call me and say, “I had a cold, and I was looking at Criterion Films, and I wanted to catch up on some of these classics, and I saw this incredible movie. It's incredible. It’s a Japanese picture. It’s called Tokyo Story. Did you ever see it?” This was last year. I said, “Yeah.” See, it took me a few years to catch up — I couldn't even understand the Yasujiro Ozu style of directing when I saw it for the first time in the early ‘70s. But this guy got it from watching it [for the first time]. And that’s very interesting to me, to be open that way to older parts of our culture, as well as newer parts of our culture. It’s the curiosity that he has about other people and other cultures.

And there’s a trust. Even if we can’t get it right away, we know we’ll come up with something. Maybe other people have relationships where they come up with it faster, but we don’t. We just work it through. For example, the scene between Leo and Bob in the jail at the end. That scene ultimately was finally written, I think, just a few days before we shot it. But working with the two of them — it could have gone so many different ways. But we had to decide: What does the picture really need? How much more is there for them to say to each other after all that’s happened? So we went that way.

It's trust. Particularly during Wolf of Wall Street, by the way. He came up with wonderful stuff that was outrageous. And so I pushed him, he pushed me, then I pushed him more than he pushed me, and suddenly everything was wild. It's really quite something. And he had a good energy too on the set. That was also important — very important — because in the mornings, I’m not really good. But I’d get on set [for Killers of the Flower Moon] and then I’d see him and Lily, and suddenly they were all like, “Hey!” So I’d say, “OK. Let’s get to work.”