We all know the heroes by name, but how about the heroines? C&I presents the women of westerns.

There is no disputing that westerns have always been a male-dominated genre, especially in the era from the 1930s through the 1960s, when Hollywood released more than 2,700 westerns to a cowboy-crazed public. But in those decades important and memorable contributions were also made by some of the silver screen’s top actresses, some of whom came to be renowned for the charisma and magnetism they brought to classic stories of the Old West. Here are some of the trailblazing stars that made an indelible impression on the genre and generations of fans.

BARBARA STANWYCK

Cowgirl Credits: Annie Oakley (1935), Union Pacific (1939), The Furies (1950), The Moonlighter (1953), Cattle Queen of Montana (1954), The Violent Men (1955), The Maverick Queen (1956), Trooper Hook (1957), Forty Guns (1957), The Big Valley (1965 – 1969)

There was something in the penetrating gaze of Barbara Stanwyck that let you know she was not just smart, but smarter than you. In the best of her 80-plus films, including several standout westerns, Stanwyck’s characters were the clever and calculating equal of any male adversary.

After an impressive turn as sharpshooter Annie Oakley in her first western, Stanwyck was top-billed opposite Joel McCrea in the epic Union Pacific, a lavish Cecil B. DeMille production. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that she became the western’s premier female star. Highlights include her ferocious performance as a rancher’s daughter out for revenge in The Furies, opening a hotel/saloon with partners Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in The Maverick Queen (based on a Zane Grey novel), and playing a western version of Lady Macbeth in The Violent Men.

Stanwyck further boosted her western cred with appearances in several TV westerns during the 1950s and 1960s, including Zane Grey Theatre, Rawhide, and Wagon Train, before beginning a five-year stint as matriarch Victoria Barkley in the classic 1960s series The Big Valley. Her impassioned performances in episodes like “Boots With My Father’s Name” were as memorable as any of her movie roles.

JANE RUSSELL

Cowgirl Credits: The Outlaw (1943), The Paleface (1948), Son of Paleface (1952), Montana Belle (1952), The Tall Man (1955), Johnny Reno (1966), Waco (1966), The Born Losers (1967)

No one would claim that The Outlaw was a classic western — or even a decent movie. But it launched 22-year-old Jane Russell to stardom, thanks mostly to an ad campaign that focused on her stunning figure. The sultry image of Russell reclining in a haystack, dress hanging off her shoulder and split to her thigh has, for better or worse, become the genre’s most iconic female image.

The film’s lascivious reputation also drew the ire of the Hollywood censors at the Hays Office — controversy that producer Howard Hughes welcomed, as he knew it would be great for box office.

There was nowhere to go but up from there, and thankfully Russell rose to the challenge of better roles in better westerns. She played two of the Old West’s most famous ladies in Calamity Jane (The Paleface) and Belle Starr (Montana Belle) and held her own opposite Clark Gable in Raoul Walsh’s classic The Tall Men. In The Born Losers, a modern-day western that replaced horses with motorcycles, Russell costars with Tom Laughlin as he introduced a character that became a global sensation — the Native American Green Beret named Billy Jack.

MAUREEN O’HARA

Cowgirl Credits: Buffalo Bill (1944), Comanche Territory (1950), Rio Grande (1950), The Redhead From War Arrow (1953), McLintock! (1963), The Rare Breed (1966), Big Jake (1971), The Red Pony (1973)

Though they costarred together in just three westerns, many fans would rank John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara alongside Roy Rogers and Dale Evans as the genre’s most famous and beloved couple. Whether trying to restore a broken family in Rio Grande, sliding down a muddy hill in McLintock!, or reminding audiences what potent big-screen chemistry looks like in Big Jake, moviegoers never tired of an on-screen partnership that endured for more than 20 years, as did a close off-screen friendship that lasted until Wayne’s passing. It was O’Hara who successfully lobbied Washington to honor Wayne with a Congressional Gold Medal that would simply read “John Wayne, American.”

Perhaps we remember their spirited arguments best, but it was a quiet moment in Rio Grande that exemplifies a connection between stars and characters as rare as it is magical: Lt. Col. Yorke (Wayne) and his estranged wife, Kathleen (O’Hara), are serenaded by soldiers singing “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen.” Both are surprised by the selection for different reasons, and all of their emotions can be read amidst the awkward silence. “This music was not of my choosing,” Yorke at last protests, to which Kathleen quietly responds, “I’m sorry, Kirby. I wish it had been.”

Even without Duke at her side, Maureen O’Hara was a force to be reckoned with in such films as The Redhead From Wyoming and The Rare Breed. And while The Quiet Man was not a western, it’s understandable if it’s your favorite collaboration between Wayne, O’Hara, and director John Ford.

RHONDA FLEMING

Cowgirl Credits: Abilene Town (1946), The Eagle and the Hawk (1950), The Last Outpost (1951), The Redhead and the Cowboy (1951), Pony Express (1953), Tennessee's Partner (1955), Gun Glory (1957), Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957), Bullwhip (1958), Alias Jesse James (1959)

Near the beginning of her career, a studio cameraman accepted a challenge to create an unflattering photo of Rhonda Fleming. He was confident everyone had a bad side, but after reviewing the film, he admitted defeat. In every frame, Fleming looked stunning.

The beautiful green-eyed redhead played sweet girls and tough gals in her western career, opposite many of the genre’s top stars. She romances Randolph Scott in Abilene Town, handles a whip as skillfully as Indiana Jones in Bullwhip opposite Guy Madison, helps Glenn Ford get clear of a murder charge in The Redhead and the Cowboy, and catches the eye of Wyatt Earp, as played by Burt Lancaster, in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

Watch any of her westerns closely and you’ll realize that Fleming did many of her own stunts — and paid the price for doing so. She was thrown from a horse that landed on top of her in The Redhead and the Cowboy, resulting in regular visits to the chiropractor for the rest of her life.

JOANNE DRU

Cowgirl Credits: Red River (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Wagon Master (1950), Vengeance Valley (1951), Return of the Texan (1952), Hannah Lee: An American Primitive (1953), The Siege at Red River (1954), Southwest Passage (1954), Drango (1957), The Wild and the Innocent (1959), Guestward Ho! (1960 – 1961)

“A Star of Movie Westerns” was the New York Times headline over Joanne Dru’s obituary, and one wonders how she would have felt about that, having often regretted being typecast in frontier roles. “While a western is a good bet for the producer and the male star, it seldom does anything for the woman in it. ... I simply hate horses — I’m scared to death of them,” she admitted to columnist Hedda Hopper.

Dru’s fate was sealed early in her career, as two of her first three films rank among the greatest westerns of all time: Howard Hawks’ Red River, in which Dru’s Tess Millay stops the climactic fistfight between father and son played by John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, occasioning a happy ending that audiences welcomed but probably didn’t expect; and John Ford’s elegiac She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the second film in his remarkable Cavalry Trilogy. She followed that up with Wagon Master, an underrated Ford classic.

And if the rest of her 1950s westerns did not reach the same pinnacle, all had their moments. Romance may not be the western fan’s top priority, but Joanne Dru made you care about her on-screen relationships, whether it was with Dale Robertson in Return of the Texan or Van Johnson in The Siege at Red River. Western lovers might be disappointed that she was not the genre’s biggest fan, but they were still always happy to see her.

TEN MORE UNFORGETTABLE PERFORMANCES

Marlene Dietrich in Destry Rides Again (1939)

Casting one of the early legends of German cinema as a character named Frenchy was not a good sign, nor was pairing an actress known for dramatic intensity with affable, laid-back Jimmy Stewart. And yet, everything about Destry Rides Again just works. Dietrich delightfully trades quips with Stewart and sings “See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have,” which became a staple of her nightclub act for decades.

Jean Arthur in Arizona (1940)

While she is likely best remembered for playing cynical city girls in Frank Capra classics like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Jean Arthur was just as captivating as Phoebe Titus, the swaggering pioneer hellcat who runs Tucson in the 1860s. She builds a freight line, fends off Apache raids, battles corrupt schemes from would-be rivals, and wins the heart of a wandering cowboy (William Holden), all in less than 90 minutes.

Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun (1946)

Producer David O. Selznick’s provocative western features Jones as the restless, tempestuous Pearl Chavez, torn between two men — a gentleman (Joseph Cotten) and a rogue (Gregory Peck). Dismissed by some critics as “Lust in the Dust,” the film is as beautiful to look at on the screen as Selznick’s earlier epic Gone With the Wind, if not always as dramatically satisfying. But Jones is bewitching as Pearl, a character described as “built by the devil to drive men crazy.”

Betty Hutton in Annie Get Your Gun (1950)

The greatest western musical ever made (sorry, Paint Your Wagon) boasts an outstanding Irving Berlin score and a boisterous performance from Betty Hutton as famed sharpshooter Annie Oakley. Judy Garland was originally cast as Annie, and film fans still wonder how the movie would have fared had she been healthy enough to finish the film (some of Garland’s scenes can be found online). But Hutton won over critics and fans, enough to make the film one of 1950’s biggest hits.

Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar (1953)

This is a Freudian western, if you’re into psychoanalytic theory; for the rest of us it’s just plain weird. But weird can be fun, especially with Joan Crawford dialing up the histrionics to 11 as no-nonsense bar owner Vienna. Her rivalry with Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge) for the love of Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden) culminates in one of the few (or is it the only?) all-female showdowns in western history.

Doris Day in Calamity Jane (1953)

This song-filled cowboy romp starring Doris Day as Calamity Jane and Howard Keel as Wild Bill Hickok is loosely based on Calamity’s life, with a nod to her apocryphal romance with Wild Bill. It’s Day at her most animated — singing, shooting, whip-cracking. The iconic song “Secret Love,” composed by Sammy Fain with lyrics by Paul Francis Webster, would become one of her most popular songs and would win the Academy Award for Best Original Song. Fun bit of trivia: According to a Turner Classic Movies article, Joel McCrea let Day ride his horse in the movie.

Jeanne Crain in Man Without a Star (1955)

Jeanne Crain became an audience favorite for wholesome girl-next-door roles, in films like the musical State Fair and her first western, City of Bad Men. So one could only imagine the “where did that come from?” shock moviegoers may have experienced seeing her as Reed Bowman, a ruthless cattle baroness in Man Without a Star. “You’re not bad with horses,” says her ranch foreman (Kirk Douglas) after Reed reins in a pair of high-spirited steeds. “I’m not bad with anything,” she replies.

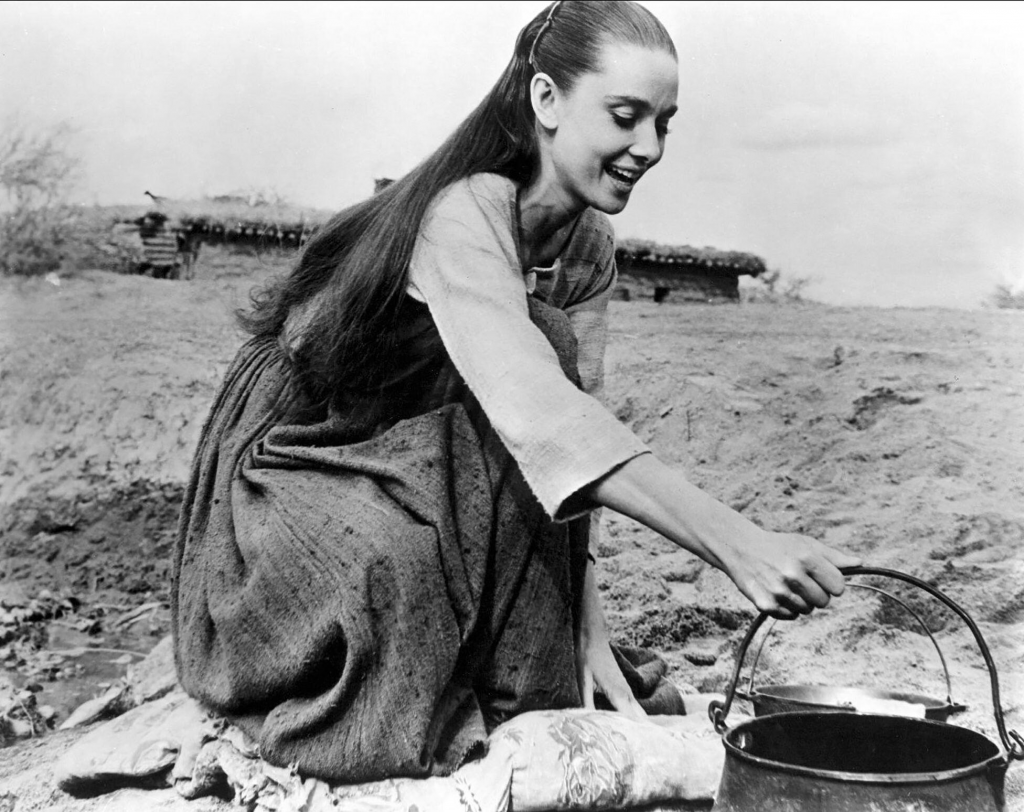

Audrey Hepburn in The Unforgiven (1960)

Audrey Hepburn was elegance and grace personified. No actress would seemingly be more out of place in a western, which is why it’s fascinating to see her in this (admittedly substandard) John Huston film as Rachel Zachary, a settler’s daughter who might be a Kiowa Indian. Her melodious voice never quite zeroes in on a prairie accent, so it’s not surprising she was one and done in this genre — especially after being thrown from a horse during filming and suffering four fractured vertebrae. Three weeks later, though, she was saddled up again and ready to ride, suggesting there was some gritty cowgirl in the princess after all.

Marilyn Monroe in The Misfits (1961)

A pall of melancholy hangs over this film, beyond what was baked into its downbeat story. It’s blue-chip material, with a script by Marilyn Monroe’s husband, playwright Arthur Miller, and John Huston directing, but watching it comes with the realization that this was the final screen bow for both Monroe and Clark Gable. Monroe’s portrayal of a fragile divorcée searching for real love is reminiscent of her troubled life off-screen, making her outstanding performance even more poignant. You can’t take your eyes off of her, and not just for the obvious reasons.

Bette Davis in “The Jailer” (Gunsmoke) (1966)

A widow, distraught over the execution of her husband, seeks revenge on Marshal Dillon. That could be a standard but still entertaining episode of Gunsmoke — but it is celebrated as perhaps the show’s finest hour from 20 seasons, because the widow is unforgettably played by Bette Davis. “You’ll get a taste of what sufferin’ is really like,” she tells Miss Kitty. “Your man’s gonna die. He’s gonna swing from the end of some hard rope till he breaks his neck.”

AMANDA BLAKE: FIRST LADY OF DODGE CITY

Everybody knows the impressive Miss Kitty, but how about the impressive woman who played her?

Television forges a bond between actors and the characters they portray. And since few shows ran as long as Gunsmoke (20 years, 635 episodes), it’s not surprising that to TV viewers and western fans, Amanda Blake will always be Miss Kitty Russell, proprietor of Dodge City’s Long Branch Saloon.

But Blake’s life was even more interesting than Kitty’s. She was descended from Kate Barry, one of the few celebrated female patriots of the Revolutionary War. She was married four times. And she was an outspoken advocate for animals and wildlife protection. Blake co-founded the first no-kill animal shelter in Arizona and ran one of the first successful programs for breeding cheetahs in captivity. In 1997, the Amanda Blake Memorial Wildlife Refuge opened at California’s Rancho Seco Park. The sanctuary is now part of the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS). The organization — which investigates animal abuse, works to alleviate the suffering of captive wildlife, and helps rescue and provide sanctuary for animals who have been victims of the exotic and performing-animal trades — received the majority of her estate when she died in 1989.

Prior to Gunsmoke, Blake was signed by MGM, but as a contract player she never advanced beyond small parts in good movies and bigger parts in bad ones, including the western Cattle Town. Thankfully, television offered a better option, with a role that matched the strength and independence of the lady who portrayed her.

But who was Kitty Russell, really? You would think 19 seasons (Blake left before the show’s final year) would be sufficient to explore everything there is to know about her, but aspects of her life and relationship with Matt Dillon (James Arness) were never resolved, lingering enigmas that likely frustrated some fans.

“I think they felt you could only go so far with it, said James Arness of television’s longest unfulfilled romance, “and then you’d have to change the character and nature of the show.” He recalled how the show received letters asking why Matt and Kitty don’t make it official, delighting producers who knew viewers would keep coming back to see if they ever did.

When the show didn’t provide answers, Blake created her own backstory to explain Kitty’s persona. “There was a man — isn’t there always? He loved her and he left her, and then they put a label on her. Kitty isn’t the type to take in washing. ... So, she drifted, and she’d drift out of Dodge if it weren’t for Matt Dillon.” Blake also suggested that running the Long Branch wasn’t her only profession. “She was a madame,” she told talk show host Mike Douglas. “That wasn’t just a saloon, folks!”

Blake's Best

For more insight into Matt’s lady love, check out these five classic Gunsmoke episodes.

“Daddy-O” (Season 2)

Kitty’s estranged father (John Dehner) arrives in Dodge City to break his daughter’s heart once again. This episode, in which Kitty references becoming part owner of the Long Branch, was the first dramatic showcase for Blake, as Kitty’s hopes for a joyful reunion quickly turn sour.

“Miss Kitty” (Season 7)

If there is one quintessential Kitty Russell episode, this may be it. Series writer Kathleen Hite always seemed to have the best insight into the character, and here we see Kitty’s maternal side as she brings a 10-year-old boy to the home of a farm couple, without telling Matt or anyone else about his presence, adding fuel to a rumor that the boy may be her son.

“The Way It Is” (Season 8)

After Matt breaks a date to take Kitty to a dance, she accepts an invitation from the abusive Ad Bellum. Another impressive Kathleen Hite script is further elevated by a memorable guest appearance by Claude Akins as Bellum — so charming one minute, so dangerous the next.

“The Badge” (Season 15)

Kitty, tired of Matt’s refusal to commit to her, and even more tired of worrying about losing him to an outlaw’s bullet, closes the Long Branch and leaves Dodge City to run a saloon with Claire Hollis (Beverly Garland). The separation between her and Matt turns into a touching exploration of the depth of their relationship.

“Gold Train: The Bullet” (Season 17)

Matt has a bullet lodged near his spine, and Doc doesn’t want to risk performing an operation to remove it. They put the marshal on a train so he can see a specialist, and the train is held up by a gang led by guest star Eric Braeden. The show’s only three-part story delivered plenty of action, drama, and romance, but its most memorable moment featured Kitty talking to Matt about the love she felt for him throughout the years.

— D.H.

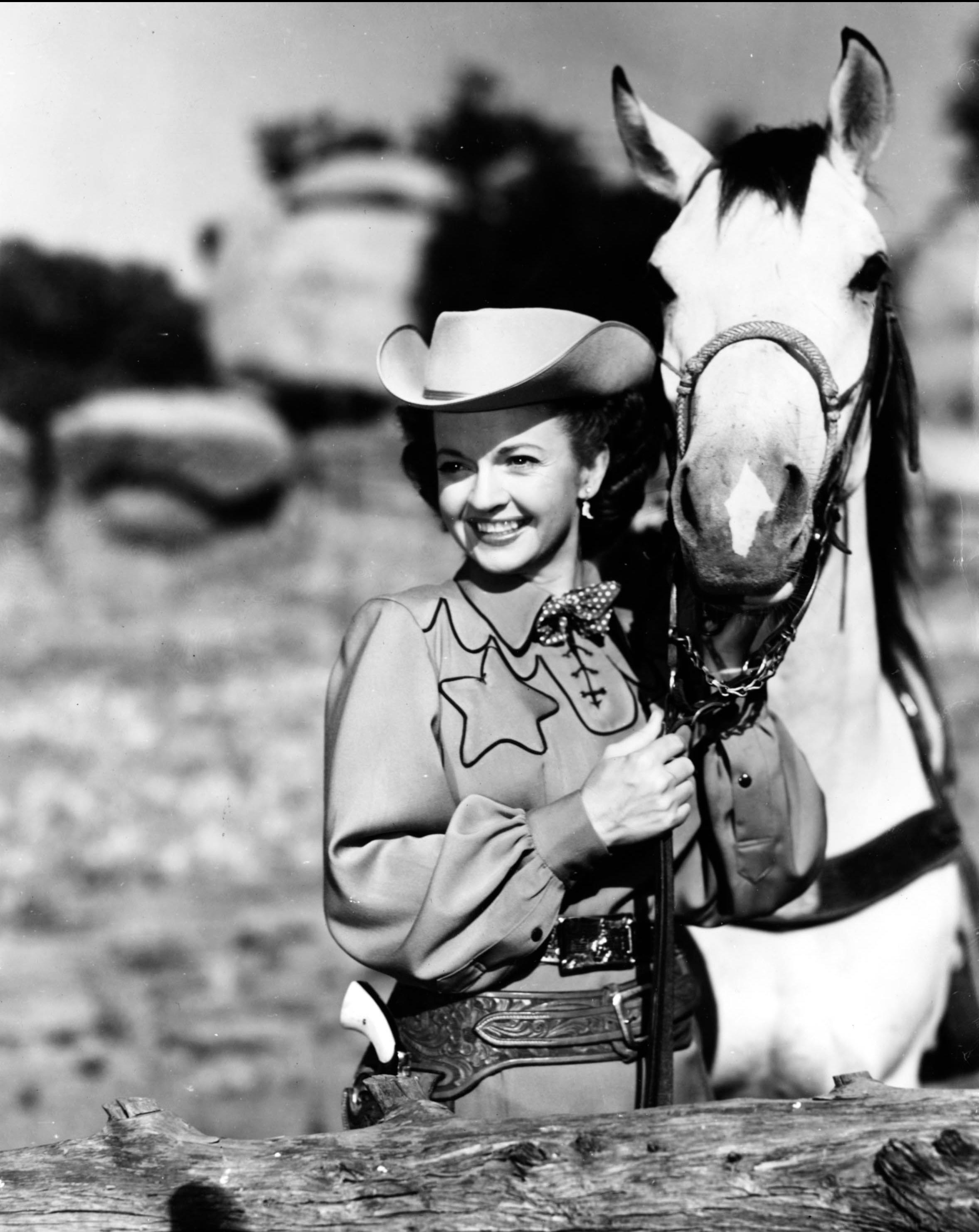

DALE EVANS: THE QUEEN OF THE WEST

Actress, singer, songwriter, and the third wife of the King of the Cowboys, Dale Evans blazed her own trail alongside of and apart from Roy Rogers.

There’s usually a “Roy Rogers and ...” before the name Dale Evans, and that’s not surprising as her rise to fame coincided with becoming the wife and costar of one of the movies’ most famous and revered cowboy heroes.

But the Uvalde, Texas-born “Queen of the West,” as she was acclaimed, was also a woman of accomplishment apart from the King of the Cowboys.

It is Evans’ name that appears on the songwriting credit for “Happy Trails to You,” the couple’s signature song, as well as “The Bible Tells Me So,” a children’s hymn still performed by youngsters in Sunday school. She was a big-band singer, the author of more than 30 books, and mother and stepmother to 13 children. She has a couple of stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — for radio and TV — and was inducted into the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in 1995 and the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000.

Roy’s youngest fans, little buckaroos wearing their cowboy hats and toy six-shooters to the Saturday matinee, were not as impressed. As Rogers recalled, “One time I gave Dale a little peck on the forehead and we got a ton of letters to leave the mushy stuff out.” That may be why she was always billed third in the credits, not just after Roy but also following Trigger, “the Smartest Horse in the Movies.”

The couple appeared in more than 20 films together, beginning with The Cowboy and the Senorita in 1944. Roy always played himself, while Dale played whatever female lead was needed to fit the script, whether that was a showboat singer (The Yellow Rose of Texas), the owner of a traveling circus (Bells of Rosarita), or a magazine reporter (Don’t Fence Me In). They usually wound up together.

A successful transition to television followed with The Roy Rogers Show (1951–1957). Who remembers the famous opening? “The Roy Rogers Show, starring Roy Rogers, King of the Cowboys; Trigger, his golden palomino; and Dale Evans, Queen of the West; with Pat Brady, his comical sidekick; and Roy’s wonder dog, Bullet.” For 100 episodes, Dale was a warm and wonderful presence at her husband’s side and a brave cowgirl who rode with him when there was trouble at the Double R Bar Ranch.

The wholesome image they presented on screen was by all accounts authentic, but their happy lives and 51-year marriage was not without sorrow. Their only child together, Robin Elizabeth, was born with Down syndrome and heart defects and died shortly before her second birthday. That experience of love and loss inspired Evans to write Angel Unaware, the first of many inspirational books she would pen and a minor classic that has been through multiple printings and helped untold couples cope with unspeakable sorrow. Told from Robin’s perspective looking down from heaven after her short life on earth, the book is credited with changing the way the country regarded children with special needs, and Evans would become known as a devoted volunteer for Christian and charitable organizations, many benefitting children.

She lived by a code. “Cowgirl is a spirit, a special brand of courage,” Evans famously once said. “The cowgirl faces life head on, lives by her own lights, and makes no excuses.”

Much of America is no longer on a first-name basis with Dale and Roy — they were household names in more innocent times, and even with 500 channels and streaming services it’s not easy to find the movies and TV shows that once made them as famous as any celebrities. But that may change soon, courtesy of a new stage musical that is scheduled to open in 2024. Happy Trails: The Real Life Adventures of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans features a script by Marshall Brickman (Jersey Boys) and music and lyrics by T Bone Burnett.

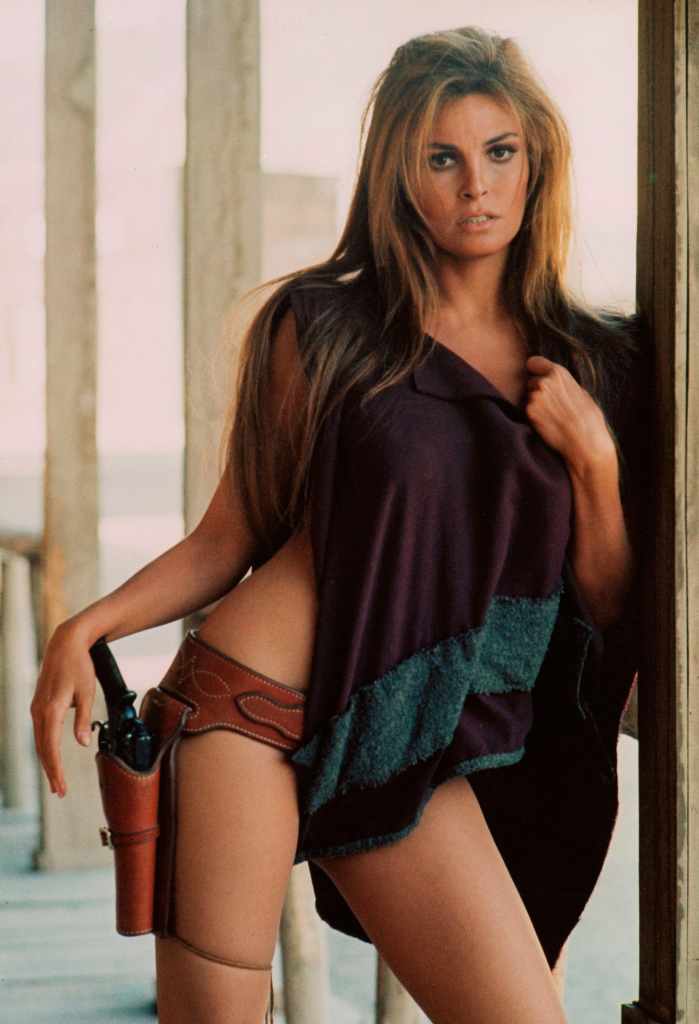

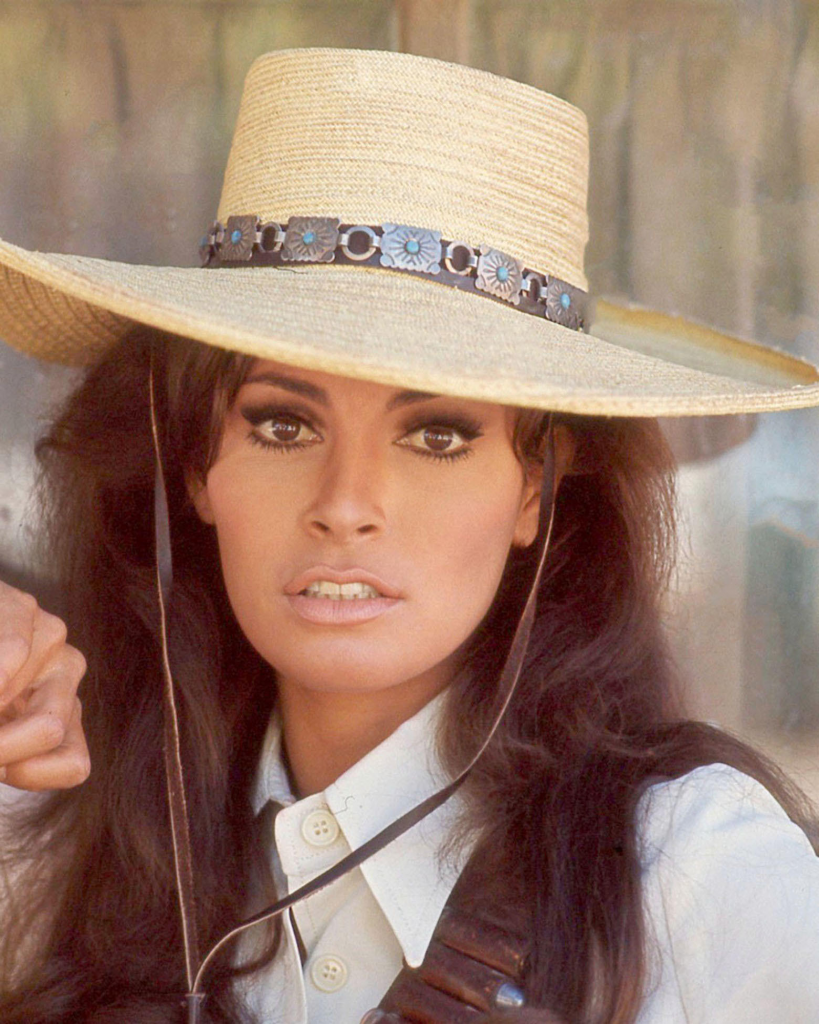

A WESTERN TRIBUTE TO RAQUEL WELCH

When the gorgeous actress and sex symbol died at 82 in February, remembrances mentioned her westerns in passing, but her screen portrayals of strong women are worth watching.

The late Raquel Welch appeared in only three big-screen westerns during her decades-long career, but she rode tall in each of them. Indeed, when she earned her spurs in Bandolero! just two years after her breakthrough performance in Fantastic Voyage (1966), no less a Hollywood veteran than James Stewart was suitably impressed: “I think she’s going to stack up all right,” he predicted of his bold and beautiful costar. He was right.

Bandolero! (1968)

The Pitch: When Mace Bishop (James Stewart) recuses his errant brother Dee (Dean Martin) and the latter’s gang from hanging for a murder committed during a botched bank robbery, they bring along the victim’s Mexican-born widow, Maria (Welch), as a hostage. Complications ensue as they’re pursued by a lawman (George Kennedy) who’s sweet on Maria and banditos who don’t aim to please.

The Rundown: Welch is credible and creditable throughout this western directed by genre master Andrew V. McLaglen (Shenandoah, McLintock!), especially whenever Maria — defiantly if not downright proudly — reveals details of her checkered pass. “I was a whore at 13,” she says, “and my family of 12 never went hungry.” She was able to marry well, she says, only because her late husband found her working in a cantina and purchased her from her father for “five cows and gun.” In short, Maria is more of a tough cookie than a distressed damsel, so it’s altogether appropriate that she’s the one who blows away the bandito chief during the exciting climactic scenes staged by legendary stunt coordinator (and eventual Smokey and the Bandit director) Hal Needham.

100 Rifles (1969)

The Pitch: Arizona lawman Lyedecker (Jim Brown) crosses the Tex-Mex border in 1912 to arrest roguish Yaqui Joe (Burt Reynolds) for bank robbery, only to get caught in the crossfire between forces led by the sadistic General Verdugo (Fernando Lamas) and downtrodden peasants who bought the weapons of the title with loot from Yaqui Joe’s heist. Welch plays Sarita, a Yaqui Indian revolutionary who knows what boys like.

The Rundown: Welch relies upon a dubious Mexican accent more than she did in Bandolero! — and plays into her sex symbol image much more, most notably when Sarita distracts an entire trainload of Verdugo’s troops by taking a shower under a water tower. (Mind you, she’s not naked — but, well, wet clothes do tend to cling.) Even so, she remains persuasively formidable when push comes to shove, especially during often-violent battle scenes where director Tom Gries (Will Penny, Breakheart Pass) has Sarita shooting just as straight as her male costars. And while she and Brown reportedly did not get along well off-camera during production, you’d never guess that from their steamy close encounter in a lovemaking scene that was borderline scandalous back in the day.

Hannie Caulder (1971)

The Pitch: After she is raped and her husband is killed by three loutish outlaws (Ernest Borgnine, Jack Elam, Strother Martin), frontierswoman Hannie Caulder prepares to mete out rough justice with training and armaments from a notorious bounty hunter (Robert Culp), a legendary gunsmith (Christopher Lee), and a mysterious man in black (unbilled Stephen Boyd).

The Rundown: It may have opened to mixed reviews and unimpressive box-office numbers, but this spaghetti western-flavored shoot-’em-up from director Burt Kennedy (The War Wagon, Support Your Local Sheriff!) has developed a loyal cult following over the years with its self-assured mashup of revenge melodrama, darkly comical bickering — perfectly cast as squabbling siblings, Borgnine, Elam, and Martin rank among the most cantankerously inept bandits in movie history — and the slow-burning, arrestingly understated student-mentor relationship between Welch as a woman determined to turn herself into a relentless avenger and Culp as the man who worries whether she’s too good a person to be as bad as she wants to be. Quentin Tarantino has claimed that Hannie Caulder in general and Welch’s Hannie in particular were major inspirations for his Kill Bill films. No doubt.

— Joe Leydon

This article appears in our October 2023 issue, available on newsstands and through our C&I Shop.