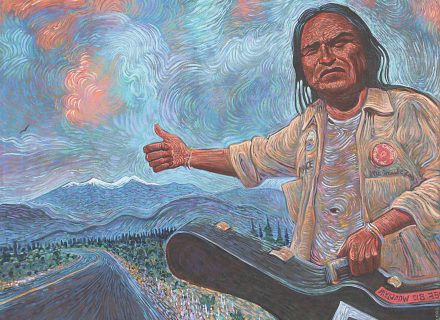

Sculptor, fashion designer, performance artist, and writer Rose B. Simpson breathes new life into the traditional Pueblo Native American pottery technique.

Real and raw are words acclaimed mixed-media Tewa artist Rose B. Simpson uses to describe her work, which ranges from ceramic sculpture, metals, and fashion to performance, music, writing, and custom cars. A skilled metalwork and spray-paint artist, she is most known for adapting traditional Pueblo Native American pottery techniques. Her diverse and unconventional figurative sculptures frequently feature an uneasy beauty and incorporate elements from popular culture. The former lead singer of the Native American punk band Chocolate Helicopter, Simpson also played in the hip-hop group Garbage Pail Kidz.

“My work,” she told Hyperallergic in a 2020 article, “is intended to translate our humanity back to ourselves. I hope that I can educate some people on issues of unconsciousness around race, gender, and history, and I hope to honor lived experiences of those who have suffered post-colonial stress disorder.”

Simpson was raised on the Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico, where she lives with her 6-year-old daughter, and she was homeschooled as a young girl by her artist mother, Roxanne. Additional early artistic inspiration came from her great-uncle Michael Naranjo, a blind sculptor; and her great-aunt Nora Naranjo-Morse, a contemporary artist. Simpson attended the Santa Fe Indian School in high school; there her passion was illustrating the yearbook with comic renditions of her classmates. She received an MFA in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA in creative nonfiction writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts.

“For me,” Simpson says, “it’s about living a life of challenge and the creative, psychological, and spiritual adventure of creating art — and I’m here for it.”

We caught up with her while she worked in her studio in Española, New Mexico.

Daughter, 2021, ceramic with glaze, wood, leather, steel, twine, grout, and studio stones, 20.5" x 16" x 9.5", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by Addison Doty.

Daughter, 2021, ceramic with glaze, wood, leather, steel, twine, grout, and studio stones, 20.5" x 16" x 9.5", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by Addison Doty.

C&I: How have the Tewa artists from New Mexico, especially your mother, influenced your work?

Rose B. Simpson: You don’t know what you have until you are not in it anymore. I was homeschooled from fourth grade until age 13 and grew up with a variety of artists, most notably my mom, as well as friends and other relatives who were orbiting the creative access. My mom is a profound ceramic sculptor and, along with several aunts and uncles, is one of the first contemporary artists in the pueblo. She was one of the first artists to develop this kind of small-scale figurative ceramics with a narrative. I didn’t know as a young girl what it meant to be a Tewa person. It wasn’t until I moved away to Rhode Island to go to school that I was able to get some perspective.

C&I: You seem to be drawn to female and androgynous subjects. Does this have to do with your mother as a role model and your now being the single mother of a daughter?

Simpson: Because I’m now a mom, my concept of empowerment has changed. I’m still fresh in the motherhood journey. My concept of empowerment as a queer person was rooted in patriarchy, which in the past meant that if you were feminine, you were weak, and if you were masculine, you were strong. I didn’t feel safe being feminine, but now giving birth to a daughter and being a single parent to a colicky baby was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Being a nurturer, putting yourself aside for another person, is true power, and I think that my work has changed because of it. I also focus on the facets of my own existence, which tends to be more feminine in nature.

Femme, 2020, ceramic, metal, and mixed media, 30" x 12" x 12", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by John Wilson White.

Femme, 2020, ceramic, metal, and mixed media, 30" x 12" x 12", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by John Wilson White.

C&I: Your earlier work seems to be much more adorned with jewelry and armorlike embellishments. How has your style changed over the last five years?

Simpson: That’s an interesting question. I was putting together a slideshow for a keynote address I was making in Cincinnati, and when I put together the show and was looking back at my older work, I realized what I was putting into those pieces were power objects — objects of intention. As I start to become more empowered, my work is changing because I need less protection and do not feel as vulnerable as I once did. Also, a lot of my pieces are now wearing necklaces and earrings as an aesthetic decision.

I did an interview with Women’s Wear Daily and the magazine asked me about my “fashion sense.” I thought a moment and said, “I don’t wear anything that impedes me from jumping a fence to get away from the cops.” But I have recently been putting on a necklace to work, which now reflects my self-worth — not just what I do, but how I value myself.

C&I: Tell us about Maria, your 1985 El Camino painted in the black-on-black, gloss-and-matte geometric Tewa style that celebrated artist Maria Martinez helped make famous.

Simpson: After studying in Rhode Island, I went back home to Española, known as the lowrider capital of the country, to study automotive design. Cars have always been a power object to me. I didn’t have the safest of upbringings, and the car became a surrogate parent and my freedom when I was able to get my driver’s license at 14.

Maria was a crumpled mess when I got her, and I had to do all the bodywork at school in Española. After welding, hammering, and putting her back together, I went from priming to the final coat of paint. The pivotal moment came about 10 years ago when we were harvesting our crops and used the El Camino to transport the beans and corn and then realized that Maria had become a vessel. The black-on-black gloss paint came next, but as anyone who has a classic car knows, the work is never finished.

Heights I (original), 2022, clay, glaze, twine, and silver, overall: 54" x 12" x 10", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by Addison Doty.

Heights I (original), 2022, clay, glaze, twine, and silver, overall: 54" x 12" x 10", Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, Photography by Addison Doty.

C&I: Tell us about your “slap-slab” technique, which seems to embrace imperfection and intuition.

Simpson: When I went to graduate school at Rhode Island School of Design, I received an incredible critique from a visiting artist who had seen one of my shows. She told me if I wasn’t there to do challenging work, it would be a waste of time. I was in a constant struggle between being seen as who I was and being accepted. In a class I decided to throw the clay sideways on a table or mat until it was very thin, maybe one-sixteenth of an inch. I then tear off small pieces and attach them to each other, kind of resembling papier-mâché.

C&I: You are incredibly well-educated, in both art and literature. Why has this been important to you?

Simpson: I think that education has been so important to me because I was homeschooled. My mom hated my graduations. I think that her disinterest in Western education made me choose to attend school even more. It was amazing for me to be able to choose from this buffet of classes, and I couldn’t get enough. I went on to get a master’s in creative nonfiction writing. I wanted to learn and understand Indigenous aesthetics and write that text for Indigenous students, but I realized aesthetics or beauty in this life was my story through my art.

See Rose B. Simpson’s newly installed series Counterculture at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. Later this year, she’ll have a one-woman show at Jessica Silverman in San Francisco.

This article appears in our October 2023 issue, available on newsstands or through our C&I Shop.