Actor, rodeo performer, artist, activist — Will Sampson was much more than the big mute Indian in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest.

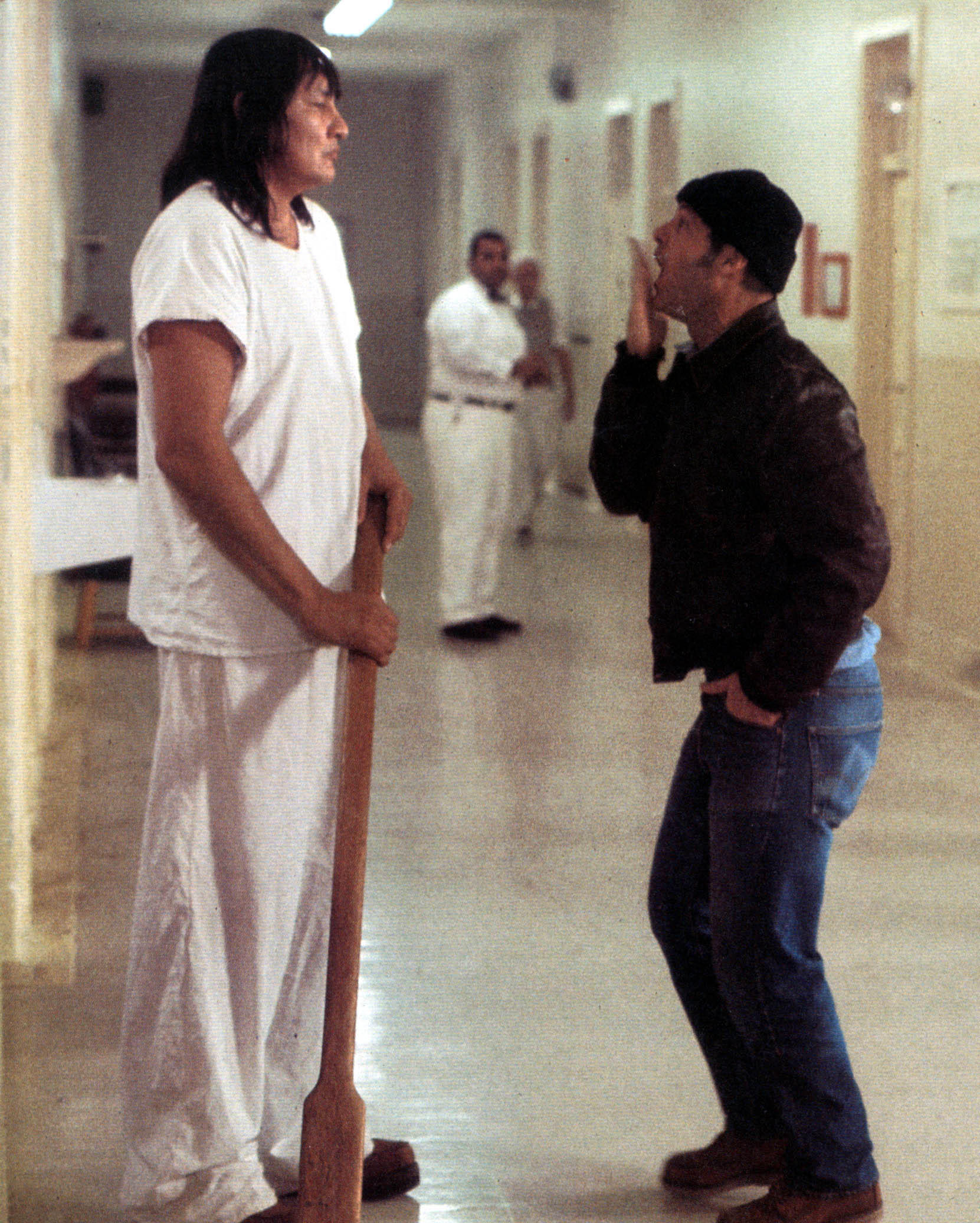

In 1975, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture. But for all the acclaim the film’s star, Jack Nicholson, received for the contrarian antics of R.P. McMurphy, and the career-defining performance of Louise Fletcher as the evil Nurse Ratched, perhaps the moment audiences best remember is when McMurphy offers a stick of gum to Chief Bromden (Will Sampson), and the “deaf and dumb Indian” responds, “Mmmmmm, Juicy Fruit.”

“If anyone could steal a scene from Jack Nicholson, Sampson is the man,” wrote The Nation in its review.

Cuckoo’s Nest was not just Sampson’s first film. It was the first time he tried acting. The Oklahoma native — a full-blooded member of the Creek Nation from Okmulgee — was bronco-busting on the rodeo circuit when producers Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas were searching for a large Native American to play Bromden. Rodeo announcer Mel Lambert suggested the 43-year-old, 6-foot-7 Sampson, who was hired after one interview.

The film’s success brought him other memorable roles, including Ten Bears in The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Crazy Horse in the 1977 Charles Bronson western The White Buffalo. Sampson also appeared in Poltergeist II and Orca and had a recurring role on the television series Vega$ as Harlon Twoleaf.

Will Sampson (Muscogee) played an unforgettable supporting role as the presumed deaf and mute Chief Bromden in 1975's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest with Jack Nicholson. Looking for a large Native American to play the part, the film's producers had found Sampson, who stood 6-foot-7, on the rodeo circuit. A rodeo competitor for two decades, he specialized in bronc-busting. He was also a talented artist.

During production of The White Buffalo, Sampson learned the producers had hired non-Native American actors to play most of the Indian roles, a common practice dating back to the earliest days of moviemaking. In protest, he refused to act alongside them, shutting production down on the film for a day.

That experience inspired the creation of The American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts, which became a clearinghouse for Indian actors. Sampson and his longtime personal assistant, Zoe Escobar, founded the registry in 1983, after obtaining a $30,000 grant from the Administration for Native Americans.

Sampson hoped the registry would offer more opportunities for Native American representation behind the camera as well.

“There are a lot of great stories of Indian scholars, Indian writers, great poets, artisans, or even doctors … true stories of great Indians,” he said in an interview. While those projects did not materialize as often as its founders had hoped, the organization did raise awareness among studio executives and casting directors about Native American talent. In the late 1980s, the registry became aware that a company called Tig Productions was casting a western, albeit one that was struggling to secure distribution from a major studio.

“I went to meet [producer] Jim Wilson,” recalled Bob Hicks, the organization’s executive director. “Kevin Costner was there. I gave them a registry book, and they gave me a script. It was called Dances With Wolves.”

That film would feature Indian actors in all the Indian roles, and it would go on to win seven Oscars, including Best Picture.

But for all his success as an actor and a prominent voice for Native American representation, Will Sampson thought of himself primarily as an artist.

After his first credited part in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest with Nicholson, Sampson continued acting, with roles including Taylor in Poltergeist II, Ten Bears in The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Harlon Two-Leaf in the TV series Vega$.

After his first credited part in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest with Nicholson, Sampson continued acting, with roles including Taylor in Poltergeist II, Ten Bears in The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Harlon Two-Leaf in the TV series Vega$.

“I’m first, last, and always a painter,” he once said. He brought some of his paintings with him when he interviewed for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, figuring that if he didn’t get the part, he might be able to sell one to the producers. He got the part — and they still bought his paintings.

His large painting depicting the Ribbon Dance of his Muscogee people is in the collection of the Creek Council House Museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, and his works have been exhibited at the Library of Congress, the Amon Carter Museum, the Gilcrease Museum, and the Philbrook Art Center. More than 50 of his paintings are collected in the 2009 book Beyond Cuckoo’s Nest: The Art and Life of William Sampson, Jr., by Zoe Escobar. Out of print, the book showcases paintings in the style of Charlie Russell that capture Sampson’s perspective on what it was to be a Native American.

In 1987, Sampson was diagnosed with scleroderma, a chronic degenerative condition that affected his heart, lungs, and skin. During his lengthy illness, his weight fell from 260 pounds to 140 pounds. He underwent a heart and lung transplant at Houston Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas, but died soon after, on June 3, 1987, of postoperative kidney failure. Sampson was 53 years old. “I will miss a great friend,” Jack Nicholson said through his agent.

Sampson’s body was returned to his childhood hometown of Okmulgee, where his family held a private Indian ceremony, in which an all-night wake was followed by burial the next day.

Will Sampson Road, in Okmulgee County (east of Highway 75 near Preston, Oklahoma), was named after him, and his legacy also lives on through his five children.

Timothy Sampson played Chief Bromden in a 2001 Broadway production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, starring Gary Sinise. Samsoche “Sam” and Lumhe “Micco” Sampson formed the Sampson Brothers duo, performers of Native hoop dance to the strains of hip-hop music. In 2018, on what would have been Will Sampson’s 85th birthday, the brothers released a musical tribute to their father called “I Know This Man”: I know this man / Who knows me more / It is through my blood / He again walks this Earth / And nears a vision / of showing the World / what Native American / really means.

Photography courtesy of Alamy Stock Photo