A shooter's guide to capturing award-winning photos of Western riders. William Shepley drops photography wisdom that he's accumulated over his years of producing beautiful Western photography.

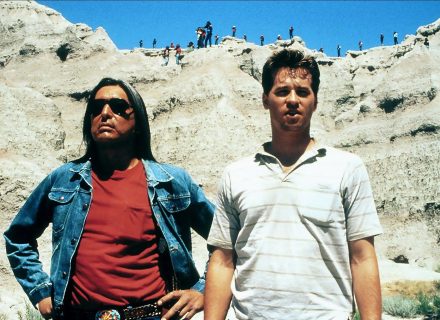

Owens Valley Horse Drive, California, 1991

Owens Valley Horse Drive, California, 1991

You don't take a photograph, you make it. — Ansel Adams

For me photography has been a journey of self-discovery, and through the optics of my camera, I developed a deeper understanding of life. It's the only visual medium that captures the art of what exists as it shows up in our everyday life from moment to moment.

In the late 1980s, I took on the challenge of shooting the equestrian culture of the American West. A university friend had married into a prominent family steeped in the culture and traditions of Western horsemanship, and from that referral I was able to build a network of connections giving me photographic access to the people who live this extraordinary lifestyle. I have photographed cowboys, wranglers, horse drives, roundups, branding, pack outfits, trick riders, team riding, rodeos, and an assortment of subject matter related to the iconic and 100 percent American-grown culture. this work was on view in the exhibition The Equestrian West: Photographs by William Shepley at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in 2020.

As a fine art photographer, I have studied the rich history of the medium. By examining the prints of the masters, I began to appreciate the visual formulas they used to create enduring works of art. In the process of deconstructing the visual elements of the famous imagery and singling out those most admired, I was able to understand my own work, and I developed a bulletproof philosophy for shooting I call the Art of Seeing. In the following examples, I use my imagery of The Equestrian West to illustrate the technique for applying the Art of Seeing to the medium of fine art photography.

Lacey, Riata Ranch, Exeter, California, 1998

Lacey, Riata Ranch, Exeter, California, 1998

The Consistent Theme

If you don't have anything to say, your photographs are not going to say much. — Gordon Parks

Important, thought-provoking, imaginative, visually stunning, and transformative photography flourishes when there is a point of departure, an embarkation point when the artist begins to experience a direction in their photographic intentions.

My mentor, Tom Knight, urged his students to create photo essays around the same topic or theme in a series. The first step in the Art of Seeing is understanding your photography in categories or themes. Go into the world and photograph it, but rather than just randomly shooting, go with intent. Shoot with a purpose and then organize your work in categories that could one day be content for a photographic project.

One of my most successful themes to photograph was a team of international Western trick riders and ropers called the Riata Ranch Cowboy Girls. I followed and photographed them for a decade, and the project came to fruition in a beautiful book titled Riata Ranch Cowboy Girls, Life's Lessons Learned on the Back of a Horse.

In the photograph Lacey, Riata Ranch, Exeter, California, 1998, I've captured a Riata Girl performing at the ranch during an event.

Wrangler, Owens Valley, California, 1991

Wrangler, Owens Valley, California, 1991

Perspective And Scale

Make yourself a master of perspective; then acquire perfect knowledge of the proportions of men and other animals. — Leonardo da Vinci

Perspective immediately establishes in the viewer's eyes the right impression of height, width, depth, distance, or position in relation to other components in the desired frame. In the early Renaissance, Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) reintroduced linear perspective, a technique where lines converge on the distant horizon.

One of the cornerstones of successful compositions, perspective denotes scale and creates a hierarchy of compositional content. The eye follows a path from closest object to furthest. The photographer, knowing this, uses scale and linear perspective to visually support the aesthetic qualities around the subject they are shooting.

In the photograph, Wrangler, Owens Valley, California, 1991, one sees perspective working its magic in an outdoor setting. The huge cottonwood trees trail off toward the horizon, gradually diminishing in size/scale as the distance grows. The perspective conveys the epic open range as the eye follows the trees to discover their end. Within this setting, the lone wrangler is comfortably positioned and silhouetted between the trees to complete the viewer's visual journey.

Purple Lake, Backcountry Sierra, California, 1994

Purple Lake, Backcountry Sierra, California, 1994

The Golden Ratio

Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist. — Pablo Picasso

The Art of Seeing is a philosophy that examines the aesthetic and artistic aspects of photography and teaches the lensman to apply as many maxims as possible when shooting on location. The rules of composition may include the Rule of Thirds, which breaks a photo down into threes both horizontally and vertically — but I suggest the Golden Ratio, a simple mathematically based method for organizing and placing objects within the composition and accentuating their importance in the overall composition.

A Franciscan friar and collaborator with Leonardo da Vinci said, "Without mathematics, there is no art," and the numerical Golden Ratio is math at work in art. Its mathematical value is 1.618 (a quick search on the web will explain the graphics). This ratio is found throughout nature and built into the structural design of plants, animals, humans, and even seashells. Its use in architecture and art goes back more than two millennia and is remarkably found throughout in the design of the Parthenon in Athens.

How does it work in photography? Imagine a horizontal line across the field of framed view in your camera's eyepiece. By estimation, divide the line into 100 points left to right with point 50 in the center. The Golden Ratio would suggest positioning the main subject or object, like a person standing or possibly a tree, at points 38.2, 50, or 68.8, which you do by simply visually dividing the space up in the viewfinder and estimating.

The photograph Purple Lake, Backcountry Sierra, California, 1994, shot in the remote backcountry of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, demonstrates the Golden Ratio. In the image the rider is approximately at 38.2, the middle horse at 50, and the second horse's head at 68.8, left to right.

Janna Copley, Will Rogers Follies, San Francisco, California, 1996

Janna Copley, Will Rogers Follies, San Francisco, California, 1996

Depth of Field

I shutter to think how many people are underexposed and lacking in Depth in this Field. — Rick Stevens

F-stop is the term used to denote aperture settings on your camera. When the aperture is closed down to a small opening, it has a larger f-stop number, for example f-22. When the iris diaphragm is turned to its largest opening, the number will be lower like f-2.8.

The higher the f-stop number, the greater the depth of focus, called depth of field. The lower the f-stop, the shallower the depth of field.

Architectural or landscape photographers may want 100 percent depth of field and will shoot at f-22 or higher to obtain complete focus. Portraitists may want to isolate the subject and apply shallow depth of field to accentuate the subject and direct the eye immediately to it.

To illustrate the use of depth of field I refer to the image Janna Copley, Will Rogers Follies, San Francisco, California, 1996. While awaiting her cue backstage, Janna hooks up with some younger actors singing in the wings. I have channeled the viewer's eye to Janna but maintained the information in the faces of her companions and the environment by using an f-4 setting.

Kansas Carradine, Louisville, Kentucky, 1998

Kansas Carradine, Louisville, Kentucky, 1998

Light

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. — Martin Luther King Jr.

The word photography, ascribed to Sir John Herschel, combines the Greek words phōtós, meaning light, and graphê, meaning drawing or writing. The word photography literally means drawing with light.

Light is the name of the game in the science and art of photography. It is the most complicated nuanced element in any composition. But light spectrum has many frequencies. There are radio waves, microwaves, infrared (IR), ultraviolet (UV), X-rays, and gamma rays, and visible light. Many specialized cameras are adapted to record light in the spectrum not visible to the naked eye. The temperature of visible light has an effect on film requiring correction filters, but digital cameras have “white balance” to automatically adjust between sunlight, fluorescent, incandescent, and halogen.

The photo example Kansas Carradine, Louisville, Kentucky, 1998 illustrates the use of reflected light. A powerful source of reflected light pouring through the large barn doors off-camera dramatically strikes the performer, a Western trick rider from the famous international troupe of riders and ropers called the Riata Ranch Cowboy Girls. Coupled with the correct depth of field and taking advantage of the “found” light source, I applied the principles of the Art of Seeing to achieve the mood and feeling of this moment and event.

Charro, Guadalajara, Mexico, 1994

Charro, Guadalajara, Mexico, 1994

Action

Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still. — Dorothea Lange

The philosophy of the Art of Seeing suggests that action be included in as many images as possible. An action could be as subtle as an inquisitive look or as raw as a punch in a heavyweight fight. Action has a rhythm to it and is linked to a chain of actions that precede it. To capture maximum intensity, like a bull rider at the peak of the buck, the photographer must anticipate the moment and be ready with shutter speed, focal length, and the depth of field necessary.

Action can be accentuated by shallow depth of field. To freeze the action, the shutter speed should be at least 1/250 of a second. The newest cameras can track objects and maintain focus in autofocus mode. I learned with a one-shot manual camera. My entire portfolio is shot on a medium-format camera called the Pentax 67. It shoots 10 images per roll of film. Digital cameras have immediate proofing, but when I started shooting, I had to wait for the film to be developed to know what I’d captured.

The image titled Charro, Guadalajara, Mexico, 1994, demonstrates how to capture action. I shot this at a private party. The owner was displaying his best horses. The gentleman trainers or charros were working the horses by performing various tricks. I readied my camera by adjusting the f-stop to give me a 3-foot depth of field and shutter speed to freeze the action. The charro reared back, and I shot right at the peak of the movement.

Salinas Rodeo, California, 1998

Salinas Rodeo, California, 1998

The Reaction Shot

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event ... the decisive moment. — Henri Cartier-Bresson

A photograph follows the principles of the Art of Seeing when there is an action and/or reaction to every compositional grouping within the frame. A reaction is a spontaneous reflex to sensual or mental stimulus. It could be the reaction of a child’s face to the sudden return of a military father from some distant country. Capturing reaction shots adds more depth of feeling to photographs. Photojournalism is full of reaction shots. They tell a story, a human story, and that resonates with the audience. It’s the spontaneous, ephemeral essence of the story summed up in what the great master Henri Cartier-Bresson famously called “the decisive moment.”

The illustration Salinas Rodeo, California, 1998 demonstrates the technique for anticipating and photographing the reactions of people and animals and capturing the decisive moment. There are three separate elements reacting in this composition. The background audience at the rodeo is reacting to the previous calf roper off-camera. The main subject is the roper still in the chute reacting anxiously for his turn. The horse’s reaction is found in its expression, its head rearing, eyes expressing excitement, and ears turned back to the rider.

Brandon Fowler, TS Ranch, Nevada, 2003

Brandon Fowler, TS Ranch, Nevada, 2003

Portrait

In a portrait, you always leave part of yourself behind. — Mary Ellen Mark

Portrait shooting is a social experience where the photographer engages the subject in a trusting relationship. The more at ease the sitter, the more powerful and truthful the portrait will be. Take a moment to study the eyes and contours of the person’s face. If it’s an older person, have them face the key light source. Direct lighting above and behind the lens helps diminish signs of age.

The eyes are the mirror of the soul and logically the most alluring and intimate feature of a portrait. In portraiture, this is where to concentrate your creative attention. A smiling face may give the impression of a happy, upbeat person but can distort the features. Better to seek out the philosophical introspective look in your subjects.

The environment of the portrait sitting tells us about the character. That’s why intellectuals tend to be photographed in front of a bookcase for an impression of study and intelligence. The objects surrounding the person in the portrait frame tell a story about the person.

Several considerations went in to the portrait of cowboy Brandon Fowler, TS Ranch, Nevada, 2003. The sun had just peeked above the distant horizon. The catchlights from the sun were reflected in the eyes, adding vitality to the portrait. I wanted a crisp, shallow depth of field, so I used a f-2.8 medium long lens. What I captured will be determined by the viewer, but I see the passion and soul of a man doing what he loves.

Laws, California, 1991

Laws, California, 1991

The Art of Feeling

Seeing is not enough; you have to feel what you photograph. — Andre Kertesz

After all the elements are stitched up and the Art of Seeing checklist thoughtfully applied, the gestalt of a photographic composition becomes an idea, a logos, and the flower of your intentions. A photographer speaks in images not words — that is his visual language, and if the photograph is successful, it communicates feeling. The

Art of Seeing is directly bound to the art of intuitively feeling.

Visualization rehearsals before an important photographic assignment prime the intuition to respond to the invisible genius of every location. In the photograph Laws, California, 1991, trail boss Lou Roeser rides herd with some very happy Western horsemen. The feeling of the riders is expressed on their faces, and their emotion is captured in the dynamic composition.

The photographer Diane Arbus said, “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.” Keeping that in mind, it’s the lensman’s mission to capture reflections of our times for the pleasure of future generations. Without photos, our memories may fail us. Without feeling, we risk communicating nothing.

For more information, contact [email protected].

From our October 2022 issue.