We set our itinerary for historical sites that tell the stories of the West.

There are a lot of ways to appreciate the West, but none beats visiting the places where horses were saddled, shots were fired, and the frontier was confronted. And nothing beats the National Park Service for making it a breeze to do just that. Though typically associated with sprawling parks filled with wildlife and other natural wonders, over half the areas in the National Park System are dedicated to preserving places that commemorate the people and events that shaped American history.

There are too many attractions central to Western history to hit in a single road trip. That didn’t stop us from compiling this short list of historic stops to help us — and you — get a jump on summer travel plans. See you on the trail.

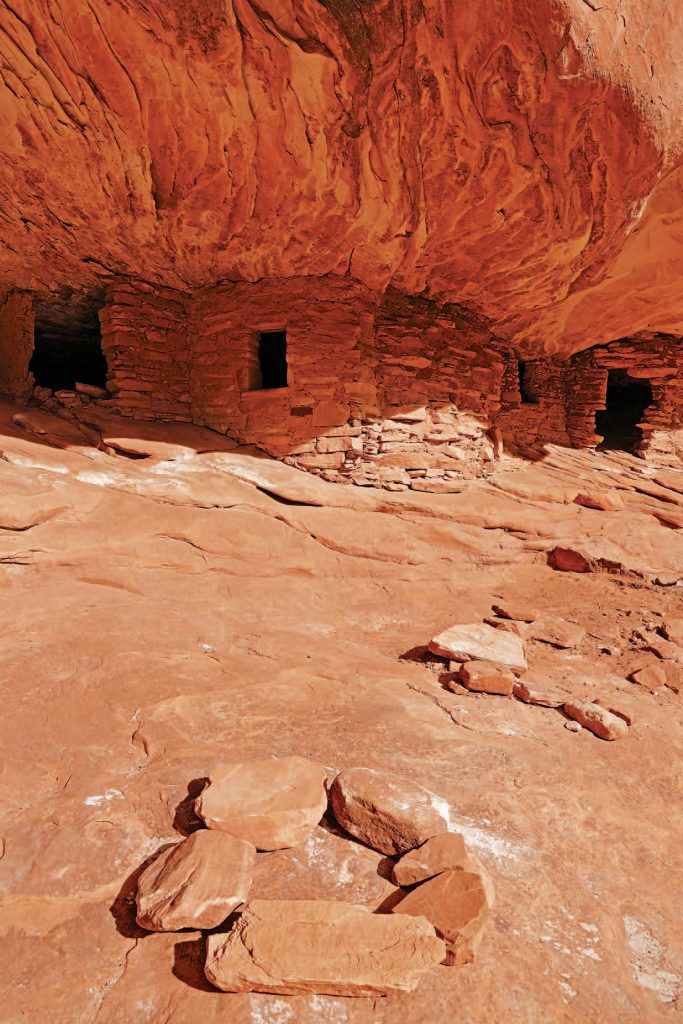

Mesa Verde National Park

Southwest Colorado

Commemorates: Ancestral Pueblo (aka Anasazi)

No matter how many times you see it, the Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde National Park doesn’t seem real. It looks more like something from a sci-fi film set or graphic novel. A spectacular remnant of the Ancestral Pueblo culture that resided here from about A.D. 550 to 1300, the park contains nearly 5,000 known archeological sites, including pithouses, pueblos, masonry towers, and farming structures. But it’s the cliff dwellings — built of sandstone, mortar, and wooden beams — that inspire the most open jaws. And photos.

The best way to appreciate the amazing architecture is with a guided cliff-dwelling tour. But a number of short and longer hikes allow for independent exploration of this wonder of human construction, where evidence has been found that builders used the sophisticated “golden ratio,” a mathematical ratio also employed at the Giza Pyramids, to construct their Sun Temple.

High point: At 8,572 feet, Park Point offers spectacular views across the rugged Four Corners region.

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park

Astoria, Oregon

Commemorates: Corps of Discovery

The legend of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is so enormous that it’s startling to walk into the party’s reconstructed Fort Clatsop and see just how small the place was where the Corps of Discovery spent the winter of 1805 – 06. The pair of low-roofed log buildings that housed 32 men, one woman, a baby, and a dog over the course of a rainy winter nevertheless stands as a symbol of the frontier fortitude that still courses through the West. Through displays, trails, canoe trips, and tours of the humble encampment at the end of the trail, visitors viscerally connect with the mission President Thomas Jefferson charged Capt. Meriwether Lewis to lead along with 2nd Lt. William Clark.

The expedition started up the Missouri River from near St. Louis on May 14, 1804, with the aim of establishing the most direct water route to the Pacific, making scientific and geographic observations and interacting with Indigenous peoples along the way. After journeying some 4,000 miles, they reached this spot on the edge of the Pacific Coast in late November 1805, opening the age of westward expansion and etching their names alongside the immortals of global exploration.

Beach break: South of Fort Clatsop, the soft sands of Sunset Beach make it great for an afternoon picnic — you can drive or walk there in the way Lewis and Clark did along a 6.5-mile route now called the Fort to Sea Trail.

Spanish Colonial Mission Trails

California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas

Commemorates: Spanish colonization

The 21 missions that comprise California’s Historic Mission Trail are justifiably famous for their beauty and their history. Located on or near Highway 101, they stretch from the first, San Diego de Alcala, in San Diego, to the 21st, San Francisco Solano, in Sonoma. Originally humble, thatched-roof structures, according California Department of Parks and Recreation (which administers them), they now dot the landscape of what was once Alta California with stately adobes. But how to reconcile the grandeur of these gorgeous structures with the cultural genocide that unfolded within their ornate walls?

“People who think the missions were places of cultural genocide and terrible population decline can look at this database, and they’ll see that people came into the missions and died soon after,” says historian Steven W. Hackel, editor of the 2006 Early California Population Project, a data bank compiled by historians chronicling the experiences of more than 100,000 Native Americans swept into California missions in the 18th and 19th centuries. “People who want to see something else in the missions can look here, too. It also shows tremendous Indian persistence and attempts to maintain their own communities within the missions.”

As with the mission trail in California, the Spanish missions of the Southwest challenge the visitor for the cultural coercion they’ll find there. Like the Native Americans in the mission system in the Golden State, those who entered missions of the Southwest seeking shelter and medical help were required to foreswear their language and customs to conform with the Spanish colonialists’ obsession with converting them to Catholicism. Tribes and interactions varied widely across the Southwest, making each mission unique, but “[in] general the missionaries sought to eradicate among missionized natives all appearances of indigenous religion and culture,” according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Encompassing more than 35 sites across Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, the Southwest missions — reflecting Gothic, Moorish, and Romanesque architectural styles — also present a logistical challenge. Visiting any one location guarantees an unforgettable interaction with Spanish history in the West, but the San Antonio Missions — a group of five missions established between 1718 and 1731 and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2015 — may be the best place to begin.

Texas trail: A 13.9-mile pedestrian hike starts at the Alamo and winds nine miles along the San Antonio River passing four other historic missions.

The Alamo (Mission San Antonio de Valero)

San Antonio, Texas

Commemorates: Texas Revolution

Itinerary, this San Antonio landmark merits its own entry as an enduring symbol of courage, military skill, and the quest for self-sovereignty. The story is well-known, yet retold no less because of it. During the Texas Revolution, a small garrison of Texan soldiers defended the Alamo against the Mexican army led by Gen. Santa Anna. With a force of 5,000 soldiers arriving in San Antonio in February 1836, Santa Anna’s siege lasted 13 days. By the end, Mexico lost 1,544 men in the fighting and 187 Texans died, including Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie. Their defeat and deaths became a rallying cry for the independent Texas spirit that echoes to this day.

Itinerary, this San Antonio landmark merits its own entry as an enduring symbol of courage, military skill, and the quest for self-sovereignty. The story is well-known, yet retold no less because of it. During the Texas Revolution, a small garrison of Texan soldiers defended the Alamo against the Mexican army led by Gen. Santa Anna. With a force of 5,000 soldiers arriving in San Antonio in February 1836, Santa Anna’s siege lasted 13 days. By the end, Mexico lost 1,544 men in the fighting and 187 Texans died, including Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie. Their defeat and deaths became a rallying cry for the independent Texas spirit that echoes to this day.

A redevelopment plan for the site has been in the works, not without controversy, since 2014. According to the San Antonio Report, the latest iteration of the plan assures that the Cenotaph — a 1930s-era monument that honors the Alamo defenders who died — will not be moved, nor will any walls or barriers around the plaza be removed nor its floor lowered — allowing Fiesta parades to continue longstanding traditions. “The three historic buildings across from the Alamo Church will not be demolished but will instead be renovated to house the visitor center and museum.” In the meantime, the Alamo Long Barrack, adjacent to the Alamo Church, has recently reopened to the public after two years of preservation work.

The most rewarding part of visiting now is the chance to interact with Alamo guides, known as “living historians.” Hands-on demonstrations re-create daily life at the time of the Texas Revolution, including essential skills such as fire starting, leather working, and frontier medicine.

Sounds and fury: Firings of flintlock muskets — the kind used during the Battle of the Alamo — take place on weekends. Bring earplugs.

Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site

La Junta, Colorado

Commemorates: Santa Fe Trail commerce

The most important trading post along the Santa Fe Trail might be a reconstruction, but it sure feels original. The minute you walk through its massive adobe walls you sense the spirit of the traders, trappers, travelers, and tribes (primarily Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa) who came together here in peaceful terms for trade in the 1830s and 1840s along the Santa Fe Trail.

There’s a self-guided tour, but it’s more fun to join a group led by a park interpreter dressed in period clothing. They’ll tell you about fur trader and rancher William Bent, who built not one but two forts (and married not one but several daughters of Cheyenne Chief White Thunder). Built in 1833, Bent’s Old Fort along the Arkansas River — which was then near the Mexican border and in what’s now southeastern Colorado— was abandoned in 1849 due to disease and disasters; it later saw service as a stagecoach stop and was also used by ranchers before finally dissolving in a flood. Bent completed a new fort in 1853, building it near present-day Lamar, Colorado, as Cheyenne Chief Yellow Wolf had advised.

Bent’s “Castle of the Plains” became, according to the Park Service, “a melting pot of different cultures and languages brought together by the prospect of trade.” Today, it’s a melting pot of resident animals, including an ox, horse, mules, goats, chickens, peacocks, and cats. The cats greet visitors, but cat skeletons found by archaeologists have led to speculation that back in the day, cats could have been used to protect the pelts from rodents.

Grassland bargain: For a must-see attraction with lots to explore, the $10 entry fee (kids 15 and under get in free) is one of the best deals on the range.

Washita and Little Bighorn Battlefields

Cheyenne, Oklahoma; Crow Agency, Montana

Commemorates: American-Indian Wars

The ghostly Montana site of “Custer’s Last Stand” recalls one of the most famous events in frontier history. But it’s impossible to comprehend the battle that took place there without the context of Washita. A visit to both sites is imperative for understanding the full arc of the tragedy unleashed by the U.S. government’s policy of relentless punishment of Plains Indians.

In the early morning hours of November 27, 1868, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led four battalions of the U.S. 7th Cavalry in an attack on Chief Black Kettle’s sleeping winter camp on Oklahoma’s Washita River. Two thirds of the village — barefoot and half-clothed — escaped downriver, but Custer and some 689 soldiers killed 59 people and took all of the horses and pack animals. Later in the morning, Custer unexpectedly found himself surrounded by 1,500 Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache warriors from the nearby camps, who began to attack when he killed 650 horses and used the remaining ones to transport the women and children taken captive. He was able to withdraw to the north and escape — his last stand would not be at the Battle of Washita.

Not quite eight years later, on June 25 – 26, 1876, that fateful, famous battle would unfold along the ridges and ravines of the Little Bighorn River. Known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass to Lakota and other Plains Indians, the Battle of the Little Bighorn was, of course, where an alliance of Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and four Arapaho, who were captives of the Sioux, dealt the U.S. 7th Cavalry a resounding defeat and killed Custer.

Today at both battlefields visitors can walk trails to get a sense of the battles from the precise locations where action occurred. As important, through outstanding visitor centers, interpretive displays, and artifacts, the sites offer austere (and weirdly beautiful) settings to reflect on and commemorate the lives lost not just at these pivotal engagements but throughout the U.S. government’s campaign against American Indians.

Still standing: The Real Bird Family’s Battle of Little Bighorn Reenactment is scheduled for June 24 – 26, 2022; littlebighornreenactment.com

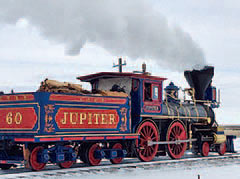

Golden Spike National Historical Park

Promontory, Utah

Commemorates: Transcontinental Railroad

Never has the single swing of a maul meant so much. Although more famous today for the namesake university he cofounded with his wife, when Central Pacific Railroad president Leland Stanford drove the famed Golden Spike into a laurelwood railwood tie at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869, he was hailed as the man who completed America’s Transcontinental Railroad. (In fact, according to the Park Service, after Stanford flubbed his ceremonial whack, the job was completed by a regular rail worker.) Nevertheless, the occasion was arguably the most transformative in Western history. In a speech on July 4, 1982, President Ronald Reagan called the landing of the space shuttle Columbia “the historical equivalent to the driving of the golden spike.”

Today, Golden Spike is a small park that carries a much larger story. Along with a location monument and replicas of the steam locomotives that, at the conclusion of the Golden Spike ceremony rolled in from the east and west tracks until they nearly touched, the park features a 1.5-mile hiking trail and two driving tours that allow visitors to motor along the 1869 railroad grade and take in the last remote phase of one of humankind’s most remarkable industrial achievements.

Drive-in theater: Reenactments of the Last Spike Ceremony are held Saturdays in summer.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park

New Mexico

Commemorates: Ancient civilization

Most of the sites on this list relate to American or even world history. If you follow TV series such as Ancient Aliens or Mysteries of the Outdoors, you might know some observers consider this massive center of ancient civilization to be a piece of cosmic history. Both shows have visited the area, which boasts 4,000 or so archaeological sites, and speculated on the possibility that its buildings, formations, and petroglyphs may have been influenced by beings from outer space.

While there’s definitely an aura of celestial mystery surrounding the desert marvel, officially the ruins of imposing structures built by Ancestral Puebloan (aka Anasazi) people (whose culture flowered here during the mid- to late-800s) “still testify to the organizational and engineering abilities not seen anywhere else in the American Southwest.” Within the park, 16 Chaco “great houses” represent the largest, best-preserved, and most complex prehistoric architectural structures in North America. Chetro Ketl is a highlight. One of the larger great houses, it has about 400 rooms and, archaeologists estimate, took more than 500,000 labor hours, 26,000 trees, and 50 million sandstone blocks to build.

Dark matter: Chaco Culture’s light-pollution-free night sky in its remote desert location makes it a spectacular site for stargazing and earned it a certification as an International Dark Sky Park from the International Dark-Sky Association.

Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

Deer Lodge, Montana

Commemorates: Open-range cattle era

Although less heralded than other sites on this list — but hailed by the Park Service as “the only cultural resource of its kind in the 401-unit National Park System” — this 1,600-acre working cattle ranch is a gem of cultural preservation along Montana’s I-90 corridor between Butte and Missoula. Once an empire sprawling over nearly 10 million acres, the original Grant-Kohrs Ranch was established when Conrad Kohrs partnered with half-brother John Bielenberg in 1866 to buy land from Canadian fur trader John Grant. Today, with 88 historic buildings and more than 10 miles of ranch roads and trails (the 2.3-mile Big Gulch Trail provides vista views), the frontier cattle era is showcased in a way that’s a blast to interact with. You’ll see things done the old-fashioned way, from blacksmithing horseshoes to haying the fields with draft teams. Extensive archive and museum collections, ranger-cowboys to talk to, and plenty of wide-open spaces keep visitors engaged.

The open-range cattle industry lasted only three decades, but its legacy lives on at this frontier landmark, summed up in 1913 by one its namesake owners, Conrad Kohrs: “They were a rugged set of men, these pioneers, well qualified for their self-assumed task. In the pursuit of wealth, a few succeeded and the majority failed. … [T]he range cattle industry has seen its inception, zenith, and partial extinction all within a half-century.” Those days may be gone, but an afternoon at Grant-Kohrs puts them right at the end of the reins.

Unique value: Bring your own horse and you can ride in the park like the cowboys who once ranged here for the Kohrs and Bielenberg Land and Livestock Company.

Manzanar National Historic Site

Independence, California

Commemorates: WWII Japanese internment

“All of a sudden we saw this barbed wire fence. That was the first time I felt criminalized. All of a sudden your life has changed.” When Hank Umemoto spoke those words to NBC News in 2015 at the age of 87, the pain of being incarcerated at Manzanar was still evident. “We really were in a concentration camp,” said survivor Joyce Okazaki.

In the aftermath of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese-Americans on the West Coast were deemed a threat to national security. In 1942, the U.S. government rounded up and sent approximately 112,000 (by war’s end the number would grow to 120,000) men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry to hastily erected “relocation centers” around the West. The military-style “camps” — in reality, prisons — would be their home for the rest of the war. “Dust, dirt, and wood shavings covered the linoleum that had been laid over manure-covered boards, the smell of horses hung in the air, and the whitened corpses of many insects still clung to the hastily whitewashed walls,” recalled another survivor.

Today, Manzanar is one of three Park Service National Historic Sites and Monuments (the others are Minidoka in Jerome, Idaho, and Tule Lake in northeastern California) where visitors can walk the grounds of an original internment camp — with visitor center, barracks, watchtowers, barbed wire, and other reconstructed facilities — to absorb the tragic history and reflect on one of the darkest episodes in 20th-century America. A fourth, the Granada Relocation Center (aka Camp Amache), in southeastern Colorado, is on track to be officially designated a National Historic Site.

Dwindling generation: For 50 years, Japanese-Americans who were incarcerated have congregated on the last Saturday of April with family and other supporters at Manzanar National Historic Site for a day of remembrance (virtually, since the pandemic).

Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site

Ganado, Arizona

Commemorates: Navajo and settler meeting ground

Pulling up today in the dusty parking lot, it’s not too hard to imagine the days in the late 1800s when you’d have ridden up and tied up your horse to the hitching posts to do some trading at the Hubbell Trading Post. The oldest trading post continuously serving the Navajo Nation, it’s notable not just for the Navajo rugs, jewelry, and Native American art still on offer inside but for its historic significance as a meeting and trading place for Navajo and settlers coming to the area to trade.

Considered the foremost Navajo trader of his time, John Lorenzo Hubbell bought the trading post in 1878, and it’s been trading ever since. “During the Navajos’ imprisonment in Bosque Redondo, or Hweeldi as the Navaj o people refer to it, they were introduced to and provided with rations that were foreign to them. This included sugar, flour, coffee, beans, and more. When Mr. Hubbell arrived, he had these items in stock, as well as new and innovative items that were being introduced into the areas off the reservation. The trader was often the intermediary between the reservation and the ever-evolving outside world,” says park ranger William Yazzie.

More than an astute businessman who would eventually own 24 trading posts, a wholesale house, and ranch properties, “Hubbell had an enduring influence on Navajo rugweaving and silversmithing, for he consistently demanded and promoted excellence in craftsmanship,” according to the Park Service. Hubbell family members operated the trading post until 1967, when they sold to the Park Service; currently operated under the Western National Parks Association, the site still has a trader who works with artists from all over the Navajo reservation, as well as neighboring tribes.

The park is best experienced on free ranger-led tours and “house peeks” of the mostly old territorial-style adobe buildings. There’s the actual trading post, which resembles a fort with its high stone walls and bars on the windows. Other buildings include the Hubbell residence, bread oven, barn, blacksmith shop, root cellar, bunkhouse, and a traditional female hogan. There’s also a visitor center, which served as a schoolhouse and a chapter house for the Ganado community; the manager’s residence, where managers would stay and operate the trading post while Hubbell was away on business; a chicken coop, which houses the resident turkey and chickens; and a corral, where the retired park horse lives.

Shopping tip: The Friends of Hubbell Trading Post Inc.’s annual auctions take place in Gallup, New Mexico, on May 7 and September 24 this year.

From our May/June 2022 issue

Photography: (Alamo) National Park Service