The fact-based western drama screens this weekend at the Pioneertown International Film Festival before opening in theaters later this year.

In 1969, writer-director Abraham Polonsky gave us Tell Them Willie Boy is Here, a fact-based film about the 1909 manhunt for Willie Boy (played by Robert Blake), a Paiute Indian ex-convict, and his Chemehuevi sweetheart (Katharine Ross), who took flight into the Mojave Desert after Willie Boy killed her father in self-defense, and were pursued by a posse led by Deputy Sheriff Christopher “Coop” Cooper (Robert Redford).

And now, as legendary radio broadcaster Paul Harvey used to say, here’s the rest of the story.

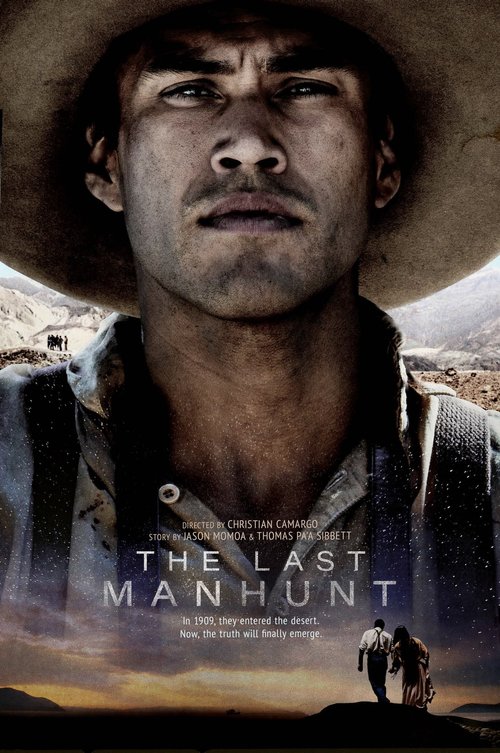

The Last Manhunt, an independently produced western co-written by executive producer Jason Momoa (Aquaman), featuring Native American actors Martin Sensmeier (The Magnificent Seven) and Mainei Kinimaka (Apple TV’s See) in the roles originally played by Blake and Ross, offers a revisionist account of the same 1909 events that occurred in and around Twentynine Palms and Joshua Tree National Park in California. Directed by Christian Camargo, who stars as the character originally played by Redford, the film co-stars Zahn McClarnon (Longmire, The Son) as William Mike, the ill-fated father of Carlotta, Willie Boy’s lover; and Lily Gladstone (First Cow, Killers of the Flower Moon) as Carlota’s mother. Raoul Trujillo (Apocalypto), Brandon Oakes (pictured above between Gladstone, far left, and Kinimaka and McClarnon), Raoul Max Trujillo (Sicario, Sicario: Day of the Soldado) and Tantoo Cardinal (Dances with Wolves) play supporting roles in the drama, which will have premiere screenings this weekend at the Pioneertown International Film Festival before opening in theaters later this year.

“It goes back to Jason,” says co-producer Martin Kistler, who last worked with Momoa on the Netflix movie Sweet Girl. “I think it was roughly 2018. Jason’s been going to Joshua Tree for a long, long, long time, for climbing and all different types of activities. And about four years ago, he was offered the chance to buy a piece of property outside of Joshua Tree Park. And so we were talking and spending some time out there. Then one of the locals, who’s also an old friend of Jason’s, made him aware of the Willie Boy story. Basically, what he said was, ‘Do you know what happened on your property that you’re about to buy? That was where the shootout with Willie Boy happened.’ And I was like, ‘What?’”

“I remember hearing about Willie Boy, the Desert Runner,” Momoa revealed to the showbiz website Deadline last year, “and was fascinated by the story surrounding him. What should be a universal story of a relationship gone bad, quickly became a muddy, complex story about the power of crooked media and how Native Americans are portrayed to the public. The true story of Willie Boy has never been told, and it’s a beautiful one. I developed the story with my team because I wanted to set the record straight, and set the spirits of this story free.”

“While he was in Joshua Tree,” screenwriter Thomas Pa’a Sibbett (Braven) told C&I, “Jason called me, and he was just like, ‘Dude, I’ve got to tell you the story.’ So he literally pitched it to me over the phone after he had just heard it. He was like, ‘We got to do it.’ Of course, we knew instinctively that there was a Native perspective here that could really drive the story and could touch an audience in a completely different way. And that’s really what our focus became —there’s this beautiful love story, this beautiful Native American love story, that we could tell.

“Also,” Sibbett added, “I started to see the connections between the Greek story of Eurydice and Orpheus, just this beautiful tale of this couple who loved each other. Eurydice gets bit by a snake and dies. She goes into the afterlife and he chases her there and tries to save her — it doesn’t quite work. So I kind of patterned the story after that to a degree — but using this true story that happened to ground our story.”

Sibbett and Momoa wrote the forward to the recently published Willie Boy & The Last Western Manhunt by Clifford E. Traftzer, the respected historian who served as technical advisor for the film, and whom they praise for helping them go far beyond 1909 newspaper accounts that characterized Willie Boy as “a scoundrel, murderer, abuser and savage.” When they sent him a copy of their preliminary script, Traftzer — a Distinguished Professor of History and Costo Chair of American Indians Affairs at the University of California, Riverside — provided invaluable insight and assistance “Dr. T began a series of conversations with us,” the filmmakers write in the book’s forward, “that led to re-writes that fleshed out the original script. This collaboration led to a moving representation that is not only historically based, but captures the emotions of the people and nuanced details of the era and the time.”

According to Traftzer, Willie Boy and his beloved Carlotta were cousins — and according to tribal customs of the time, a union between them would be viewed as incest. Nevertheless, the couple managed to meet in secret from time to time — despite the strong disapproval of Carlotta’s intimidating father. “Willie Boy was afraid of William Mike, who was a shaman,” Traftzer told C&I. “And he had been a former warrior in the 1860s. He had fought the Mojaves during a Mojave-Chemehuevi war on the Colorado river. He was a tough guy, is what I’m saying. He could be a very sweet guy, but if you’re looking for trouble, you found it. And he had this added ability as a shaman to hurt people.”

But on a fateful September night in Banning, California, Willie Boy approached William Mike with a .30-30 rifle in hand to demand the right to marry Carlotta. There are conflicting accounts about what happened next, but Traftzer says that based on his research — including descendants of William Mike — he has concluded that “since William Mike was shot in the face and it blew his brains out, it’s most likely that William Mike grabbed that gun to take it away from him. And the barrel was facing his face and it went off and killed him. Even the family believes it was an accident. But nevertheless, here we have William Mike dead.”

After that, Traftzer said, Willie Boy “went and saw the family and the mother and told Carlotta, ‘Let’s go. And she went with him willingly. He did not force her or rape her — those are stories that were told by the posse that pursued them. He loved this girl and he wanted to take off with her. And she went willingly. And the mother said, ‘Well, if you're going to go do that, go do that.’ So off into the desert they went.”

Martin Sensmeier is Willie Boy and Mainei Kinimaka is Carlotta in The Last Manhunt

Some say Carlotta eventually committed suicide after days of fleeing through the desert heat. Others say Willie Boy shot her himself, lest she slow him down. And still others insist she was killed by a stray bullet fired by the posse pursuing them. Whatever the cause of her demise, Willie Boy did not survive much longer. But their legends continue

“Jason is a good friend of mine,” Zahn McClarnon told C&I, “and he’s got some property out in Joshua Tree. He came to me a few years back with the idea that these stories he had heard from the Chemehuevi people in that area should be told in a movie. As soon as he told me ‘We're thinking about doing the Willie Boy story,’ I thought it was a wonderful idea. And he asked me to come on board to do one of the parts. And also to help him cast the movie as well. And I was happy to do so. We had a lot of fun out there in the desert, even though it was pretty hot.

“Actually, I was working another job at the time. So I had to fly back from Quebec City in Canada to Palm Springs, back and forth, for about a month. And it was tough to do that, to work out the schedules, etc. But it was important that we told that Willie Boy story from a Native perspective, and that we had the Chemehuevi tribe behind us and supporting us.”

Long before production began in and around Banning, Momoa and Sibbett spoke with tribal leaders of the Twentynine Palms band of Chemehuevi — including a few who were direct descendants of people involved in the Willie Boy story. They were given a copy of the screenplay during this meeting, and told that if they had any objections to their bringing that story to the screen, Momoa and his team simply would not make the movie. Fortunately, the tribal leaders granted their approval, and shooting started with a ceremony performed by members of the Chemehuevi, Serrano and Cahuilla tribes.

Director Christian Camargo sees The Last Manhunt as a correction of ill-informed and/or exploitative historical accounts as well as an entertaining — and, he hopes, enlightening — motion picture.

“I, too, have been coming out to Joshua Tree for a very long time,” Camargo told C&I. “I’ve been living out here pretty much, as far as my only residence, since 2006. And so I’m very familiar with the Willie Boy story — and also the sort of oral tradition of the tribes surrounding the area. They didn’t really write things down, so the white man’s story of Willie Boy became the written record, and the oral tradition was just sort of sidelined. It’s something that everyone always talks about, but we never see anything about.

“So this is our mission, to sort of be a vessel for the native voices to come through. This is not a traditional shootout western, you know? Jason and the whole group, we decided to make an art-house western that has a very simple story. But the spirit of the land and the spirit of the culture has to come through almost in silence. You know? And so it’s going to require people to wrap their heads around the fact that they're not watching a — quote, unquote — Jason Momoa film, and that this is part of a deep spiritual healing process that this area needs. Because the Willie Boy story got tremendously corrupted. And there is are a lot of the evil spirits that surround that lore, and they need to be calmed. They need to be quieted. That’s what we’ve tried to do.”