Marie Watt's career, like her work, unfolded organically — even serendipitously.

It’s just past noon in Portland, Oregon, and artist Marie Watt is on a lunch break. She’s in the middle of a printmaking session using blankets and text with Julia D’Amario, a printmaker who she’s worked with before. “Our last collaboration was over a year ago,” Watt says. “It feels like we’re hitting the ground running.”

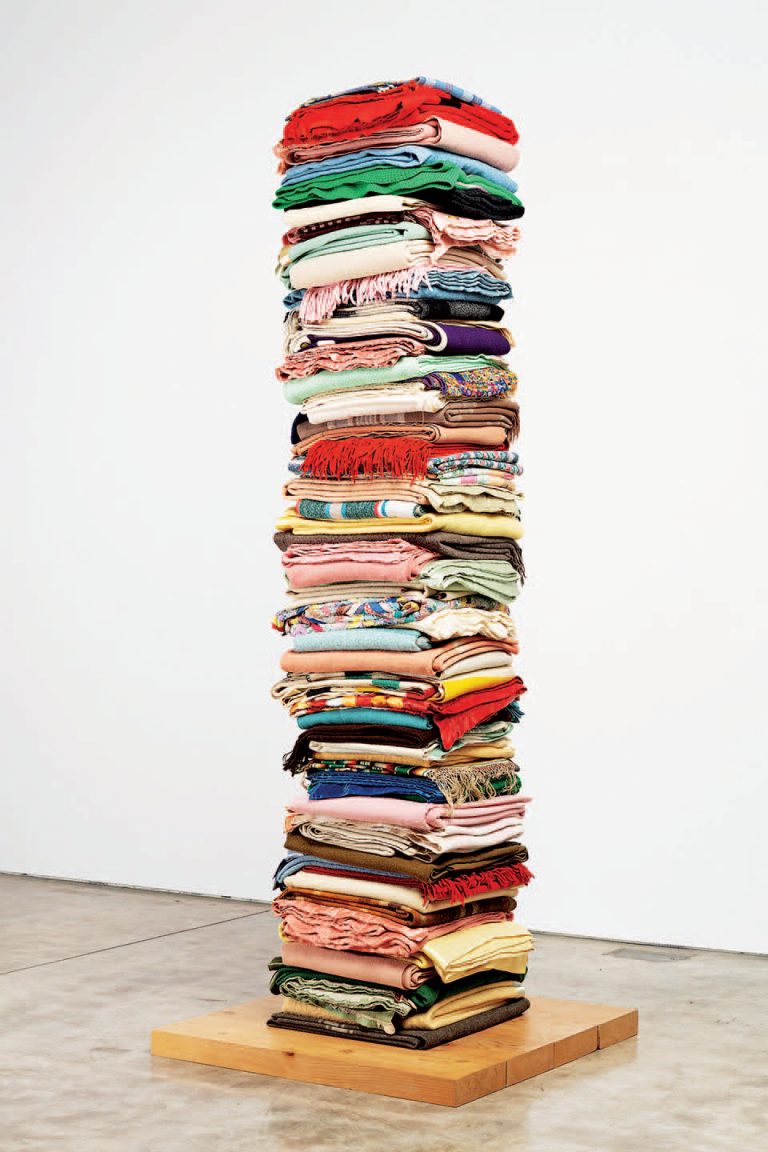

Her project today is a snapshot of what she’s best known for: using humble everyday objects as touchstones, blankets in particular. Since she first rummaged through the city’s thrift stores in 2003, scavenging for wool blankets, anything around $5 apiece to make the totemlike tower sculptures of stacked blankets, she has relied on reclaimed objects as a primary medium for her artwork. Beyond that, her process is largely collaborative. That may mean working with a printmaker, like she’s doing today, or gathering blankets and their individual histories from friends and strangers, and weaving that element into her pieces, too.

“Blankets are markers for memory and history,” says Watt, who’s Seneca, one of six tribes that make up the Iroquois Confederacy. That’s her mom’s side of the family; on her dad’s, she’s German-Scottish. “When I was making these columns of folded and stacked blankets, I had a friend who said, ‘This one reminds me of my grandmother.’ In my tribe, we give away blankets to people who are witnesses to life’s important events. I saw my experience to these [blankets], but then I saw other people’s experiences, too, how blankets were highly regarded objects.”

Now 53, Watt grew up in Seattle, the oldest of two, always doing something that sparked creativity. “My mom always had activities for my younger sister and me that engaged our hands and our senses. I learned how to embroider and work with clay. I took pottery lessons. We went to the Burke Museum on the campus of the University of Washington. It was a natural history museum, where I saw totems, dugout canoes, and feast spoons.”

She didn’t think that she’d grow up and be an artist — not until a professor at Willamette University, a liberal arts school in Oregon, encouraged her to pursue it as a career. After she graduated, she was accepted to the Institute of American Indian Arts and got a degree in painting and printmaking; after that, she got an MFA in painting and printmaking from Yale. After garnering early regional attention at PDX Contemporary Art and Portland Art Museum in Portland, Oregon, her work has gone on to be widely featured at many other prestigious venues, including the National Museum of the American Indian George Gustav Heye Center, in New York; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Whitney Museum of Art in New York; Seattle Art Museum; and Denver Art Museum.

It’s a career that, like her work, unfolded organically, even serendipitously. When she was preparing for a show for the Heye Center 17 years ago, she realized it would take too much time to finish sewing the pieces on her own. “So I invited a few friends over and I said, ‘I’ll feed you if you’ll help me sew.’” Her first sewing circle was born. “I quickly realized I was less interested in sewing as a means to an end to finish a project than as a way of gathering, and getting to know and connect people.”

Since then, Watt has hosted more than a hundred sewing circles, all with the intent of building community as much as creating art. “I think the sewing circles set the table for multigenerational and cross-disciplinary conversations that build community and pass on knowledge. This is a traditional model of teaching and learning that isn’t just Indigenous — it’s the way ancestral knowledge has been transmitted from one generation to the next.”

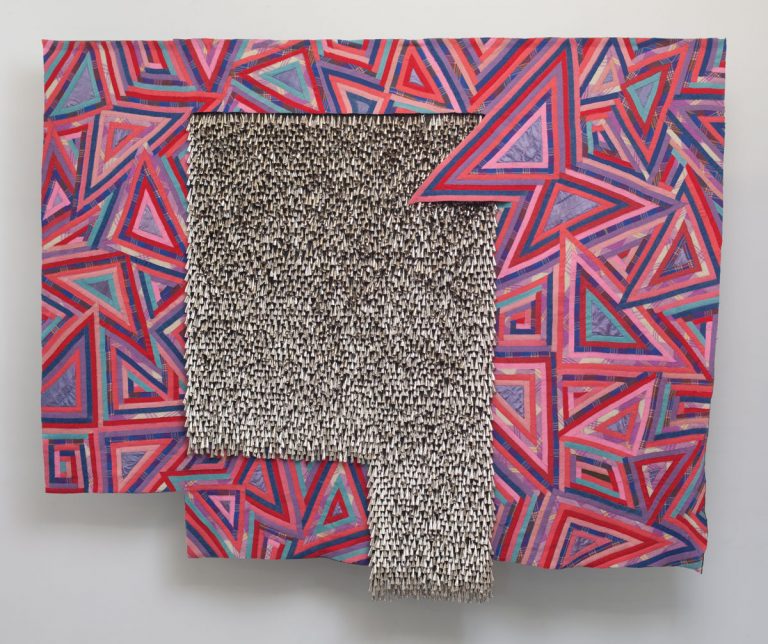

Today at the printmaking studio, she’s arranging long rectangular-ish pieces of blankets into shapes that resemble deer horns, with cutouts of words that relate to the “mini-gods” Sapling and Flint. “Sapling and Flint are twins in the Iroquois creation story,” Watt says. “One occupies day, and the other occupies night. One grows things, and the other destroys things and plays tricks. We need both of them to create balance in the universe. I tend to think we all need a little Sapling and Flint in each of us.”

Marie Watt’s work is on view through May 24 in the exhibition Companion Species at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and May 23 – August 22 in Each/Other — a collaborative exhibition with Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota) — at Denver Art Museum. Visit the artist at mariewattstudio.com.

Photography: (Cover image) Courtesy Marc Straus Gallery/Photo by Kevin McConnell

From our May/June 2021 issue