The Oscar winner chats about his involvement in bringing the frontier drama The World To Come to screens, and the fine acting balance his role required.

At the start of The World to Come, a stealthily compelling period drama about the quiet desperation that can drive men and women to extremes, we are introduced to Abigail (Katherine Waterston), the stoically forlorn wife of Dyer (Casey Affleck), an emotionally withdrawn farmer. Abigail is grieving after the death of their young daughter, a victim of diphtheria, but reveals the depths of her despair only in journal entries that serve as the movie’s narration. (“The water froze on the potatoes as soon as they were washed. With little pride, and less hope, we begin the new year.”) Dyer possibly is every bit as bereft, but he is unwilling to reveal his feelings — and incapable of consoling his wife. As he sees it, life simply must go on. Abigail isn’t quite so sure.

Indeed, Abigail doesn’t really begin to display signs of life until she meets Tallie (Vanessa Kirby), a newcomer to their isolated area of 1850s upstate New York. Tallie is such a bold, brazen life force that Abigail cannot help being drawn — slowly, awkwardly — out of her workaday misery. It takes little time for a close friendship to blossom, and just a little while longer for that friendship to evolve into something more intimate. Dyer suspects something is amiss — and appears jealous of his wife’s confidant, though he would never admit that in a million years — but, true to his nature, he refrains from raising serious objections.

Unfortunately, Finney (Christopher Abbott), Tallie’s brutish and controlling husband, isn’t nearly so restrained in his reaction.

Subtly directed by Norwegian-born Mona Fastvold (The Sleepwalker) from a terse yet eloquent screenplay by Ron Hansen and Jim Shepard, The World to Come has been a long-gestating labor of love for Casey Affleck, the Oscar-winning actor (for 2016’s Manchester by the Sea) whose credits also include Gone Baby Gone (directed by his older brother, Ben Affleck), Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven trilogy, The Old Man & the Gun, and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. In fact, he came close to directing the indie drama at one point — but turned over the reins to Fastvold after deciding that a female filmmaker would be better suited for the story.

“Casey was obviously a part of the package,” says Fastvold, “but he left it completely up to me, even to whether or not to cast him as Dyer. He was actually a little bit on the fence, and was like, ‘Oh, maybe you should cast someone who seems more like a farmer.’ But I thought that Casey’s sort of natural vulnerability would bring a very interesting layer to the character. And so he agreed to play the part as well as serve as producer.”

Affleck sat down for a wide-ranging interview before The World to Come had its U.S. premiere at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. Here are highlights from our conversation, edited for brevity, clarity, and flow.

Cowboys & Indians: Just how early in the production process did you get involved with The World to Come?

Casey Affleck: Right from the start. A few years back, I did The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, which was based on a novel by Ron Hansen, who I think is one of our best living American Western writers. I became friends with him, and so we started talking about trying to find something else to do together. He’s friends with a writer named Jim Shepard, and he sent me two of Jim’s stories. One was about a Cuban baseball player, and one was about two women on a farm who find each other during a terrible low point in their lives, and fall in love. I liked that one a lot. I thought it was a movie.

C&I: This was around 2006, right?

Affleck: Yes. Ron started developing it, adapting it with Jim Shepard. Those two guys wrote about — well, I’d like to say 10 drafts. [Laughs.] I mean, they have their day jobs. They both teach at a university and they did this on the side. But what they wound up writing is what I think is one of the best scripts that I’ve ever been able to work on. I really do. And I know the movie is coming out at a time when people aren’t, like, lining up in droves to see little, tiny movies about such things. But the writing of it is just so fine, so smart, and I think that it might be found, in the same way that The Assassination of Jesse James was. You know, that movie didn’t do very well when it opened. But over the next decade or so, it started to appear on every critic’s list of the best movies of the last 100 years. Now, it’s a kind of beloved classic. I hope that The World to Come will similarly find an audience. It’s a very different movie than Jesse James, but the writing is just as beautiful.

C&I: At one point, weren’t you planning to direct The World to Come?

Affleck: Yeah, I was planning on directing it myself the whole time we were working on the script. But then I thought the better of it. I felt like, this was a story about these two women, and there was a woman who wanted to direct it, and maybe it was a good opportunity to let her do so, and just be a supporting player.

C&I: What made you think Mona Fastvold was the right woman for the job?

Affleck: Well, she seemed to really love the material. I thought her casting choices, which were entirely her own, were just brilliant and inspired. I thought that it was a hard movie to cast. Katherine Waterston and Vanessa Kirby were really great choices, and that says a lot about a director.

C&I: At what point did it occur to you, “Hey, wait a minute. We’re going to be going through all of these seasons in this story. Where are we going to be able to shoot this? How long are we going to get to shoot this?”

Affleck: Those are the million-dollar questions when you start a movie — especially a movie that is not going to have a $100 million budget. I wanted to make it really small. Like, I did a movie called A Ghost Story that David Lowery directed. The budget was about $200,000. To me, it was proof of something that I’ve always believed, which is: The smaller you get, the more nimble you are, and the more you can do. It’s the middle ground that’s really hard. You can either waste money on giant movies, or you can do tiny movies where you don’t have any money. These tiny ones where you don’t have any money are just more fun, and you can get a lot more done because you’re flexible.

Click on the slideshow for more images

C&I: OK, you mentioned David Lowery, who also directed The Old Man & the Gun. So we have to ask: What was it like working with Robert Redford on that one?

Affleck: You know, whenever you work with someone that famous, people will always ask, “What was so and so like?” And you always say something like, “Oh, he’s such a nice guy. Such a nice gal.” But in his case, it’s really, really true about him. He’s just a gentle, beautiful, considerate, humble guy. I mean, sure, he’s more of a god than a human in movie terms. But, really my takeaway was, “Boy, that’s just one of the nicest guys I ever met.” And I wonder how you can stay that way and still have the career that he has had. I really mean it.

C&I: You only had a couple scenes on screen together — he played an aging bank robber, and you were the cop on his trail. But the final scene was all the more enjoyable because, just as you were leaving the room, you stroked your nose with your finger — just like Redford and Paul Newman did while playing con men in The Sting. Whose idea was that?

Affleck: [Laughs] Yeah. Newman and Redford made that little gesture to one another as a secret code of being in on something together. And I just think it’s so delightful. So, there I was in a scene with Redford and in many ways, it was a kind of button on his career as being maybe the most lovable bank robber in the history of cinema. So how could I not do that? I tried to do it as subtly as I possibly could, but I needed to make some homage to his greatness, and in particular, his greatness in that movie.

C&I: Getting back to The World to Come: What made you decide to shoot in Romania?

Affleck: Like I said, I wanted to be small and nimble, and to be able to shoot all four seasons in two shoot periods — start and stop, start and stop. Vanessa and Katherine are both very successful and busy people, and so they weren’t going to be able to come and go like that over four seasons. So we settled on Romania, in part because it’s very, very cheap to shoot there. But also because after the summer, the fall turns to winter pretty quickly, so you can get snow. We did two small shoot periods, in the summer and in the early winter. We just tried to get as much snowy weather as we could.

C&I: Tell me a little bit about how you developed your character. I mean, not so much when you were working on the script, but when you were shooting on a day-to-day basis. Once you started interacting with other actors as their characters, did you change your mind about Dyer? Maybe there’s something you hadn’t thought about before that surprised you?

Affleck: That’s such a good question. I think that every time I come to a movie, I have a certain idea of who the character is and how they’re going to behave in the movie. And the other actors do, too. But then, it’s a little bit like watching two teams who both have their game plan — and then they suddenly get onto the field, and have to adjust. It’s like Mike Tyson said, “Everyone’s got a plan until you get punched in the face.” That’s what doing a scene is like. You’re constantly making adjustments, especially with two actors who are so smart, and have such a cerebral approach, like Katherine and Vanessa. They’re very well prepared, just really talented, and they’re going to bring a lot to the game.

C&I: Can you think of specific adjustments you had to make?

Affleck: Well, I thought that my character, Dyer, was someone who essentially really loved his wife, and was trying to get through a period of mourning the daughter that they’ve lost, and come together as a couple. And that her relationship to Tallie was one born out of, basically, desperate grief. She finds a connection with somebody else, and discovers love there. And the movie is this exploration: Where does love come from? But when I got there, I found other people had different ideas about how the relationship between those women came to be, and what it said about my character. So I had to pivot. It’s something that I would do every single day on any movie that I care about, really, and I care about most of them. You show up and you’re constantly thinking about the way things are going to be and what you can bring to the day — and then you have to pivot, because it’s a team sport.

Click on the slideshow for more images.

C&I: It seems to me that playing Dyer required a pretty tricky juggling act by you as an actor. One wrong move, and you come off as oppressive. A different wrong move, however, and you come off as a victim. And, really, the character is far too complex for either of those easy labels. Was it a difficult balance for you to strike?

Affleck: Yes, it was, but it wasn’t struck by me. I think that the writers were very careful to make sure that he didn’t stray a little to the left and become an oppressive husband, and didn’t stray too far to the right and become a victim. Dyer was written as all the parts in the scripts were. They’re all people who are trying to do the best that they can. And if they might neglect others — it’s not because they’re terrible people, but because they have blind spots.

C&I: Finally, I’d like to go back to The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. You received Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations for your performance as the man who ultimately killed the legendary outlaw. But, you know, Bruce Dern has often talked about dealing with angry John Wayne fans who blame him for killing The Duke in The Cowboys. Have you ever run into anyone who’s still holding a grudge because you killed Brad Pitt?

Affleck: [Laughs.] That’s just a funny question. No, I never have. I think it’s because that movie tried to do something different with the western. They took on one of the bigger icons of the outlaw West, Jesse James, and said, “Look at this. Here’s a guy who was made famous by these dime novels of the period, that were mostly written and read in the Northeast by people who had never been robbed by Jesse James, and who had never had a family member shot by Jesse James, and who had never lost their fortune because Jesse James stole it callously and beat them within an inch of their life with the handle of a gun.” They didn’t have any experience, so they glorified, they glamorized, they sexed up Jesse James in these little dime books.

Affleck: [Laughs.] That’s just a funny question. No, I never have. I think it’s because that movie tried to do something different with the western. They took on one of the bigger icons of the outlaw West, Jesse James, and said, “Look at this. Here’s a guy who was made famous by these dime novels of the period, that were mostly written and read in the Northeast by people who had never been robbed by Jesse James, and who had never had a family member shot by Jesse James, and who had never lost their fortune because Jesse James stole it callously and beat them within an inch of their life with the handle of a gun.” They didn’t have any experience, so they glorified, they glamorized, they sexed up Jesse James in these little dime books.

The movie was saying, “Look at what this person really was.” Let’s reimagine the idea of the outlaw, and without disparaging him, or sort of flattening it into some message movie, and ask, “What was this person really like? And what was this young kid like, the one who shot him? Is he really the villain?” Like, who do we want to think of as the villain here? This young kid, Robert Ford, had the courage to do what the Pinkertons, or anybody else, couldn’t really bring themselves to do, which is catch and kill a serial killer. Because, basically, Jesse James was a serial killer. He had killed that many people.

So, who do we want to think of as a hero in this situation? The movie actually presents Robert Ford in a very sympathetic way, and takes a pretty compassionate look at his life. The last quarter of the movie, I think, leaves the audience feeling like, “Wow, this kid had a lot of grit, man. He took on somebody who was absolutely terrifying.” I think it leaves you feeling like, not hating him, but sort of with your mind changed about who Jesse James was and who this guy was. So, to answer your question, no one says to me, “Oh, you’re the son of a bitch that killed Jesse James.” Usually, all they say is, “Man, that movie broke my heart.”

The World to Come is available for rental or purchase on various streaming platforms.

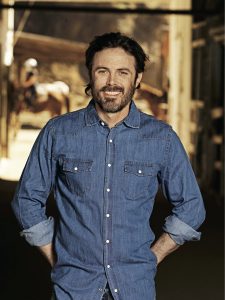

Casey Affleck was shot on location at Sunset Ranch Hollywood. Styling by Ilaria Urbinati; shirts by Double RL. Grooming by Barbara Guillaum. Photography by Robert Lynden.

From our April 2021 issue.