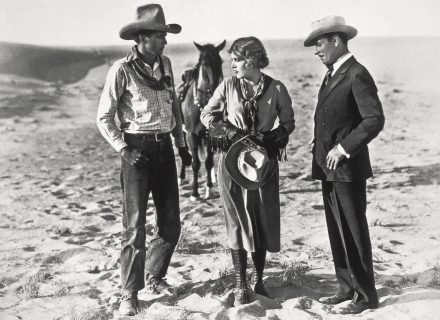

Tom Mix was the silent screen’s King of the Cowboys.

On the south side of town in Oklahoma’s former territorial capital of Guthrie, there’s a building that once housed the Blue Belle Bar. Founded in 1889 in the wake of the Land Rush, it was one of Guthrie’s most popular watering holes. But the saloon’s main claim to fame might have less to do with its genesis and more to do with a certain one-time bartender. Before he found fame in Hollywood, the Blue Belle is where future western silent movie star Tom Mix once poured drinks for real outlaws, real frontier marshals, and real gunfighters.

A rumor goes around that on the east wall of the saloon once hung a life-size chart of Mix mapping the locations of 12 gunshot wounds and dozens more other bodily injuries from knife fights and broken bones he had sustained during his days as a cowhand and rodeo rider and as an actor doing his own stunts as one of the top male movie stars of the silent-film era.

The Pennsylvania-born Mix had drifted west into Oklahoma Territory working on the 101 Ranch alongside Will Rogers, breaking horses and herding cattle. He had ended up in Oklahoma in 1902 after marrying his first wife, Grace Allin, that year. She didn’t like his being in the service, so he went AWOL and they headed out west to escape the Army.

After leaving the Blue Belle and Guthrie, Mix turned up next as a performer in the 101 Ranch Wild West Show, where he debuted in 1905, dazzling audiences with his horsemanship and shooting skills. The birthplace of the show was the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch — a cattle operation that worked 110,000 acres in the Indian Territory of Oklahoma and put on yearly rodeo extravaganzas that eventually expanded into the widely traveled wild West show. In its debut year, the show drew close to 80,000 attendees, with attractions that included Apache prisoner Geronimo, Buffalo Bill Cody, Bill Pickett — and Mix.

That same year — probably due to his connection with the 101 Ranch Wild West Show — Mix rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade with a cavalcade of Western cowboys. He continued amassing cowboy cred and résumé brighteners by winning national rodeo championships for riding and roping in 1909 and 1910.

In 1910 Mix was asked to appear in the documentary Ranch Life in the Great Southwest. The film was a financial hit and launched a movie career that would ultimately boast some 366 westerns full of flashy stunts, fistfights, and shootouts that left audiences wanting more. You might say he was John Wayne before there was a John Wayne.

Mix seemed suited to onscreen fiction, and storytelling was in his blood. In real life, he was something of a fabulist: “He was the goddamndest liar who ever lived,” declared famed rodeo cowboy turned Hollywood stuntman Yakima Canutt. “But never did he lie to hurt anybody. It was always done in showmanship.”

Mix became the star of Saturday-afternoon matinees, in which the hero wore a white hat, kissed his horse, drank only sarsaparilla, and rescued women from a fate worse than death. If the plots were formulaic, his stunts weren’t: His westerns stood out for death-defying exploits that saw Mix and his horse, Tony, leaping through glass windows and over deep gorges. The stunts kept his audiences enthralled; Mix, meanwhile, suffered mounting injuries.

But the silent action suited Mix. His voice had been affected by a gunshot wound to the throat during his days cowboying, and from having his nose broken multiple times in bar fights.

His films quickly made Mix one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood. And he cut quite the famous figure offscreen as well. Flamboyantly dressed in his white 10-gallon cowboy hat, decorated boots, and a body-length coat, he had his initials lit up in neon lights on his ranch house outside of Los Angeles. His style and wealth were extravagant, and so were his marriages — five in a 30-year span.

As the silent era came to a close, Mix was getting old, and his style of westerns had passed. When he asked friend John Ford for work, the famed director told him audiences now wanted something different.

For a while Mix found circuses lucrative. He made his last feature — the 15-chapter serial The Miracle Rider — in 1935. Five years later, at age 60, he filled a custom aluminum briefcase-style suitcase with money, traveler’s checks, and jewels, set it on the backseat of his yellow super-charged 1937 Cord 812 Phaeton convertible coupe with an externally mounted spare tire on the rear deck (one of only two made — the other reportedly belonged to film legend Barbara Stanwyck), and headed east to visit old friends.

Eighteen miles south of Florence, Arizona, he came up to barriers at a bridge washed out by flooding. Swerving twice, he finally overturned in a gully. The case flew forward, striking Mix from behind, breaking his neck and killing him.

Had it been a horse and not a car and had the good guy survived, it would have been an ending fit for the motion pictures.

You can find the case that killed him at the Tom Mix Museum — not in Guthrie, but in Dewey, Oklahoma, where Mix lived with his third wife and where the museum has an 8½ x 11-inch version of the chart showing his many and much-mythologized gunshot wounds and other injuries.

Visit the Tom Mix Museum and Guthrie’s Oklahoma Territorial Museum online. Visit Guthrie — the largest contiguous urban historic district on the National Register of Historic Places — online here.

Photography: Images courtesy PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

From our January 2021 issue.