Native American veterans are finally getting some long-overdue recognition with a national memorial in Washington, D.C.

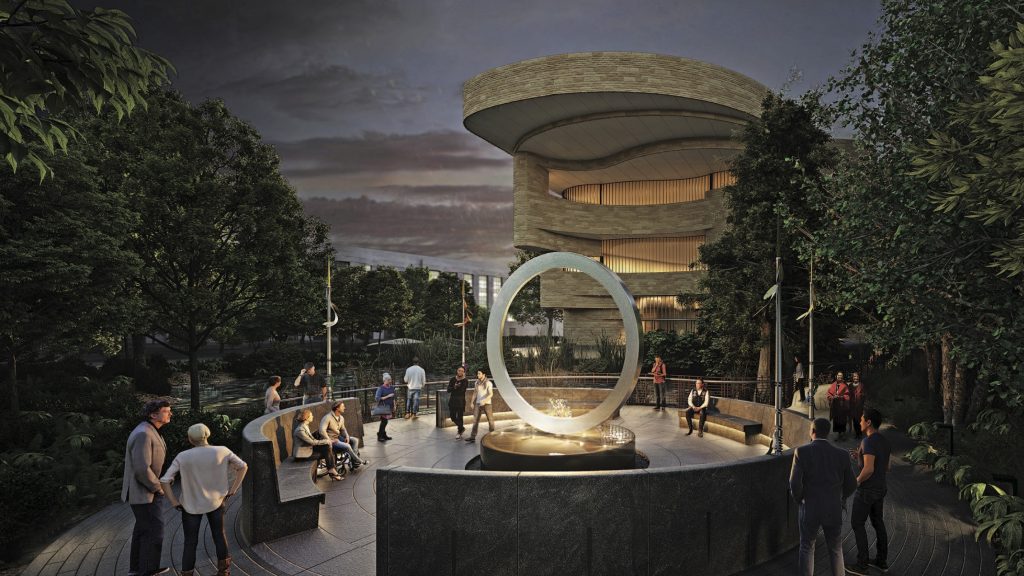

Considering the extraordinary history behind the new National Native American Veterans Memorial, the story of the hawk that consecrated its location on the National Mall doesn’t seem so far-fetched. Shortly after the design was selected in 2018, the memorial’s designer, Harvey Pratt, a Cheyenne-Arapaho-Sioux artist from Oklahoma, traveled to Washington, D.C., to join a committee on the site where the new landmark would be constructed.

The hawk that lives near the memorial site and was present at the ground-breaking ceremony

The hawk that lives near the memorial site and was present at the ground-breaking ceremony

“We were giving a presentation at the final site — about 30 of us were standing there — and a hawk flies out of the southwest and it lands right on the spot we chose and starts hopping around,” Pratt recalls. “I said, ‘Look, he’s dancing.’ Then he flew up in a tree and sat there the whole hour we were there.

“He came out of the southwest. That’s the direction where the Creator lives. My oldest brother and grandfather’s name was Hawk. My ancestors came there to approve what we’ve done.”

More auspicious yet, the visitation has proved no coincidence: Pratt’s hawk has since been observed frequently perching in a tree near the memorial, and a smaller hawk has begun hanging out on one of the armatures of the time-lapse camera system installed atop the museum to document the construction of the memorial.

You could hardly ask for more fitting guardians to watch over the site as it awaits its official introduction to the country. The memorial’s unveiling and dedication had been planned for Veterans Day, November 11, 2020, in the nation’s capital. Though the pandemic has put those plans and the Native Veterans Procession on hold for now, the spirit of the long-belated recognition has not diminished.

Located on the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian, the monument is an elevated stainless steel circle balanced on an intricately carved stone drum with water flowing across the surface of the drum. The design incorporates elements of earth, water, fire, and air. Ripples emanating from the water feature represent vibrations from the drum, calling people from around the nation. “This is not a monument people will stand back and look at, but one they will gather within,” says Rebecca Head Trautmann, the museum’s project curator for the memorial.

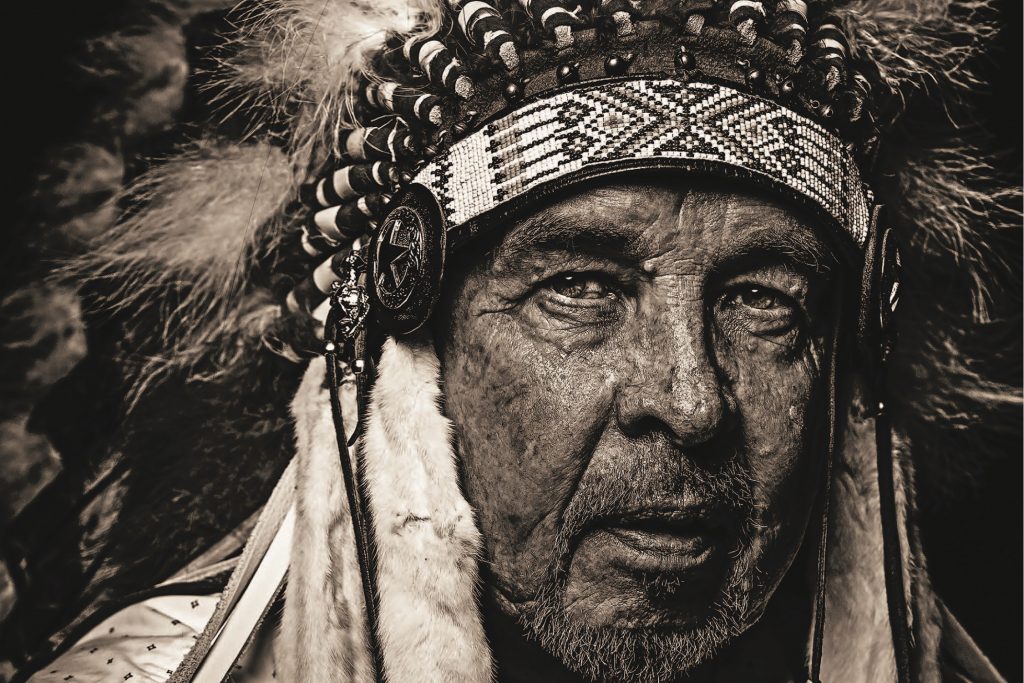

Artist Harvey Pratt in ceremonial headdress

Artist Harvey Pratt in ceremonial headdress

National recognition of Native American military veterans has been a long time coming. Legislation authorizing the memorial’s construction passed in 1994. Sponsor Senator John McCain of Arizona and co-sponsors Daniel Akaka (Native Hawaiian) of Hawaii and Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Cheyenne) of Colorado, all military veterans, were among its initial sponsors in the U.S. Senate. But the memorial’s legacy dates to the 1700s and honors all Native American men, women, and military families who have fought and sacrificed in every major military conflict in American history.

“When the memorial is unveiled, the country will recognize — for the first time on a national scale — the enduring and distinguished service of Native Americans in every branch of the U.S. Armed Forces,” according to the museum. “This memorial carries the heavy responsibility of respectfully acknowledging American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian veterans ... reminding all Americans of our national obligation to honor this inspired legacy.”

Outsize Influence

Widespread awareness of Native American participation in the U.S. military tends to start and stop with World War II. For good reasons, the famed Navajo code talkers — who radioed secret battlefield messages in a coded version of their language that remained indecipherable to enemy code breakers — have been widely celebrated. Pima Indian Marine Ira Hayes, who helped raise the Stars and Stripes over Iwo Jima, in an event captured in the famous Joe Rosenthal photograph, lives on in “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” made famous by Johnny Cash, and the 2006 film Flags of Our Fathers. Fans of the World War II comic book Sgt. Rock may recall Little Sure Shot, the Apache guide and sharpshooter who served as one of the pillars of the “Combat-Happy Joes” of the fictional Easy Company.

Yet starting with the Revolutionary War — when Indigenous soldiers, largely of the Iroquois Confederacy, fought on both American and British sides — Native Americans have fought as part of the American military. They battled on both sides of the Civil War. They fought against but also alongside U.S. troops in the Indian Wars. They took part in operations in Cuba, the Philippines, and the Boxer Rebellion in China.

But particularly since World War I — when Choctaw, Comanche, Cheyenne, Osage, and Yankton Sioux were used as the first Native American radio code talkers — they’ve consistently served at higher rates per capita than any other ethnic group.

“Although most Indians in 1917 were not subject to the draft because they were not U.S. citizens, they enlisted in astonishing numbers,” wrote Herman Viola about World War I soldiers in his book Warriors in Uniform. Indian troops often volunteered for or were used as advance scouts, among the most dangerous positions in combat. About 5 percent of Native American troops were killed or injured in the Great War, compared with a 1 percent casualty rate for the entire American Expeditionary Force.

“They established a remarkable record of patriotism and selflessness during a conflict that they had no readily apparent reason to join or recognize,” Viola wrote. “Nonetheless, they contributed to the victory beyond their tribal numbers or resources.”

That outsize contribution has never abated. Some Navajos were so enthusiastic to join World War II they showed up at induction centers toting their own rifles and shotguns. As they had done to Germany in World War I, the Iroquois Confederacy, or Six Nations, declared war on the Axis powers, in 1942. That same year, at least 99 percent of all eligible Native American males had registered for the draft. “Had all eligible American males enlisted in the same proportion as tribal people there would have been no need for the Selective Service System,” Viola wrote.

An estimated 10,000 Native Americans served in the Korean War. Another 42,000 were in the military in the Vietnam era. Today, some 31,000 serve on active duty, reserve, and national guard — many have fought, died, or been injured in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other battlefields around the world. About 133,000 veterans identify as American Indian, Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian. Of these, 11.7 percent are women, compared with 8.4 percent of all other ethnicities.

Native American soldiers have also established a reputation as some of the most fierce and poised fighters in the field. A Crow soldier named Walks Over Ice related a story to Viola about a new recruit during the Vietnam War who asked to be transferred to his platoon. “My dad was in World War II and he said, ‘If you ever get into combat find an Indian and he will keep you alive,’ so I want to be with you,” explained the recruit. Walks Over Ice directed the new soldier to his brother, who was already serving in the recruit’s platoon.

“My brother kept him alive,” Walks Over Ice said.

Inspired Design

Such a long and complex legacy posed a unique challenge for the 120 entrants who formally submitted designs to the memorial’s blind-juried competition.

“There’s this idea of a monolithic Native American culture, which, of course, doesn’t exist,” Trautmann says, noting there are more than 500 federally recognized tribes in the United States. “It was important the memorial design be inclusive of all these traditions.”

From left: Side gunner Gus Palmer (Kiowa) and aerial photographer Horace Poolaw (Kiowa) in front of a B-17 Flying Fortress at MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida, ca. 1944

Prior to the competition, museum staff worked with an advisory committee of Native veterans to hold 35 consultations across the country gathering input from tribal communities on themes and ideas the memorial should address. Initially, Harvey Pratt wasn’t interested in submitting a design. A friend had invited him to one of those public meetings in Shawnee, Oklahoma. But Pratt fended off his friend’s encouragement to submit an entry.

“Oh, no, there’s going to be people entering from all over the damn place; those are big firms with large staffs competing for that,” he told the friend. “I’d be just wasting my time.”

Deep down, Pratt was intrigued. An artist since grade school in the 1950s, when a teacher encouraged his talent by paying for art supplies out of his own pocket, Pratt has always shown an ability to blend multicultural influences into his singular artistic vision. He sold his first painting as a high school student at St. Patrick’s Indian Mission School in Anadarko, Oklahoma. A crucifixion scene in which all of the figures were Indians, with war bonnets, feathers, and lances, it was so good the priests could hardly complain of heresy. One helped him sell it for $90.

“In those days $90 was two weeks’ pay for a lot of people,” Pratt says. “Man, the lightbulbs went off for me when that happened.”

Pratt went on to a distinguished 50-year career in law enforcement. From 1972 to 2017, he was with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation as a narcotics investigator, assistant director, interim director, and internationally sought-after police forensics artist. Throughout his career, suspect drawings, skull reconstructions, age progressions, and soft-tissue postmortem renderings he drew based on victim and witness descriptions helped lead to the arrest of murderers, rapists, and other criminals, including the Green River Killer, BTK Killer, and I-5 Killer. All the while, he worked on the side as a commercial artist and sold his work in galleries.

During an inspection trip of American battle fronts in late 1943, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander in chief of the Allied forces in the South Pacific, stands with (from left) Staff Sgt. Virgil Brown (Pima), 1st Sgt. Virgil F. Howell (Pawnee), Staff Sgt. Alvin J. Vilcan (Chitimacha), Sgt. Byron L. Tsingine (Diné), Sgt. Larry Dekin (Diné).

After his friend dragged him to a second memorial planning meeting, this one in Oklahoma City, Pratt said, “Let me dream on it.” Not long after, he sat down at home with a yellow legal pad and began sketching. The basic design flowed quickly, like an ethereal inspiration.

“The first time I saw Harvey’s sketches I knew they were special,” says his wife, Gina. “I looked at them and thought, You did it! It left me speechless for a short time. It was very profound.”

Pratt’s son, also an artist, encouraged him to take the design to Oklahoma City’s Skyline Ink to be animated. “I said, ‘I don’t think I can afford you guys,’ ” Pratt says. “They said, ‘Don’t worry about it — we believe in what you’re doing, we want to support you.’ ” As the project picked up steam, he partnered with Oklahoma City’s Butzer Architects and Urbanism. The veteran team there gave physical shape to Pratt’s design, influencing choices of concrete, steel, stone, lighting, pathways, and other construction details.

“They made it even better than what it was,” Pratt says.

Indomitable Spirit

Harvey Pratt in Vietnam

What makes Pratt’s winning design all the more astonishing is that in a competition that drew entries from around the world, the blind jury selected the work not only of a Native American — “Who would’ve thought a Cheyenne-Arapaho-Sioux guy would win this thing?” Pratt says — but of a military veteran.

Inspired by the warrior tradition of his community and a charismatic uncle who fought in World War II and Korea, Pratt joined the U.S. Marines shortly after becoming disenchanted with college art classes following his high school graduation. He was sent to Vietnam in 1963 as part of a reconnaissance unit whose job was to recover downed helicopter pilots and protect the U.S. air base at Da Nang.

“I designed our platoon guidon,” he says. “It was called ‘Hughes’ Hellions.’ Our lieutenant’s name was Edward Hughes. He was killed in Vietnam.”

Pratt’s experience in that painful conflict — he believes he was one of the first Native Americans sent to Vietnam — informs the design of the memorial, which, among other things, is intended as a place of peace and remembrance.

“One thing we heard over and over again in community consultations was a wish for the experience of visiting the memorial to be a healing and contemplative one,” Trautmann says. “Something that surprised us was a strong preference expressed for the memorial to be located in a quieter place, a contemplative and reflective place rather than one of the prominent visible places, such as right on Independence Avenue.”

In a setting so serene even a hawk can relax for an hour, the memorial will surely become a spiritual beacon. But with its four lances that rise around the drum, it also embodies the unconquerable spirit that provides the answer to one of the questions most frequently asked of all Native American service members: Why are a people who have been so historically mistreated by the American government so willing to take up arms on behalf of that government?

Pratt today

The answer lies in the warrior culture that remains pervasive across Native American communities.

“Ours was a race of fighting men — war was our occupation,” a Native American World War I soldier named James Kaywaykla explained in answer to the question about a war now more than a century gone.

The memorial committee found the same commitment to serving and protecting everywhere it consulted with Native American communities. There’s a reason powwows traditionally begin with a presentation of flags by a color guard. No figure drove the point home more powerfully than a veteran who stood at a meeting hosted by the Southern Ute Indian Tribe in Ignacio, Colorado.

“Our great-great-grandparents’ bones are in this land that we live on, so we still think of it as our own. We’re willing to put forth our lives to keep enemies away.”

The museum will mark the memorial’s completion day with a virtual ceremony that acknowledges this milestone and honors the service and sacrifice of Native veterans and their families. The dedication and the procession will be rescheduled when it’s safe for large groups to gather again. For up-to-date information on the memorial, visit the National Museum of the American Indian online.

Photography: Images courtesy National Museum of the American Indian, Abraham Farrar, Katherine Fogden, Smithsonian, 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw, Harvey Pratt

From our January 2021 issue.