Both progress and injustice define the complicated history of official policy toward American Indians.

Thirty years before he became the first president of the United States, George Washington already was lusting after the American West.

Born into wealth in colonial Virginia, Washington was a 27-year-old Army commander in 1759 when he made Mount Vernon his full-time residence. He would spend the next four decades raising the roof of the modest farmhouse and transforming it into a mansion.

He also moved the main entrance, reorienting the mansion from eastward-facing to westward, symbolizing his conviction “that the future lay in those wild and wooded lands of the Ohio Country,” biographer Joseph Ellis writes. Washington had been a surveyor as a young man and was adept at getting the lay of the land. As a 21-year-old major in 1754, more than two decades before the beginning of the Revolutionary War, he had ventured into the Ohio River Valley to contain French ambitions there. His actions would inadvertently give rise to the French and Indian War, but seeing the fertile frontier beyond the Allegheny Mountains would reinforce for him the importance of controlling the western edges of a nascent United States, and of connecting it with the eastern seaboard. Writes Ellis: “Even when ensconced on the eastern edge of the continent at Mount Vernon, Washington spent a good deal of his time and energy dreaming and scheming about virgin land over the western horizon.”

Thus began the quest for the West, an obsession with expansion and development that would capture the fantasies of America’s chief executives well into the 20th century. From Thomas Jefferson to Lyndon B. Johnson, presidents — often guided by such divine principles as Manifest Destiny — laid claim to Western land and natural resources.

But this master narrative, the triumphal story of how the West was won, is only one side of the proverbial coin. The other side, a more nuanced version of history, tells of the devastating effects westward expansion had on America’s Indigenous peoples.

In this counternarrative, the presidents who did the most to build the West often committed the most egregious acts against Native Americans. Likewise, presidents who consistently rank among history’s worst sometimes did the most for their Indigenous constituents.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson, lauded for doubling the size of the United States with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, was the first president to propose the removal of Indians from their homelands. Jefferson nursed a “passion for land,” biographer James Rhonda wrote. He possessed a romanticized vision of the West as a “garden of boundless fertility” where “the American republic would thrive and remain forever free.”

Although he never pretended the West was empty — once referring to it as “the crowded wilderness” — Jefferson nonetheless believed that “Indian country belonged in white hands.”

Jefferson sent four groups of explorers on western expeditions (including Lewis and Clark). He also oversaw 33 treaties with tribes — often after driving them into debt and forcing them to give up acreage to pay their bills.

Jefferson’s Indian policies fueled the more violent strategies of Andrew Jackson, whose Indian Removal Act of 1830 was the force behind the Trail of Tears.

Abraham Lincoln

As Abraham Lincoln labored to protect the rights of African Americans during the Civil War, he turned a blind eye to Native Americans and the wars raging in the West.

“The wars against Native people just simply went on as usual, even during the Civil War and abolition,” says historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. “Lincoln’s campaign for presidency had appealed to land-poor settlers who demanded that the government open Indigenous lands west of the Mississippi.”

In 1862, Lincoln pushed Congress to adopt the Homestead Act, the Morrill Act, and the Pacific Railroad Act, all of which transferred large tracts of Indigenous land to corporate or settler interests. With these land grabs, the federal government broke multiple treaties with Indian nations. When tribes resisted, the Army forcibly removed or massacred them.

Under Lincoln’s direction, the Army slaughtered Cheyenne and Arapaho people at Sand Creek, Colorado; imprisoned nearly 10,000 Navajo and Apache men, women, and children at Fort Sumner, New Mexico; and publicly hanged 38 Dakota warriors in Minnesota in what remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

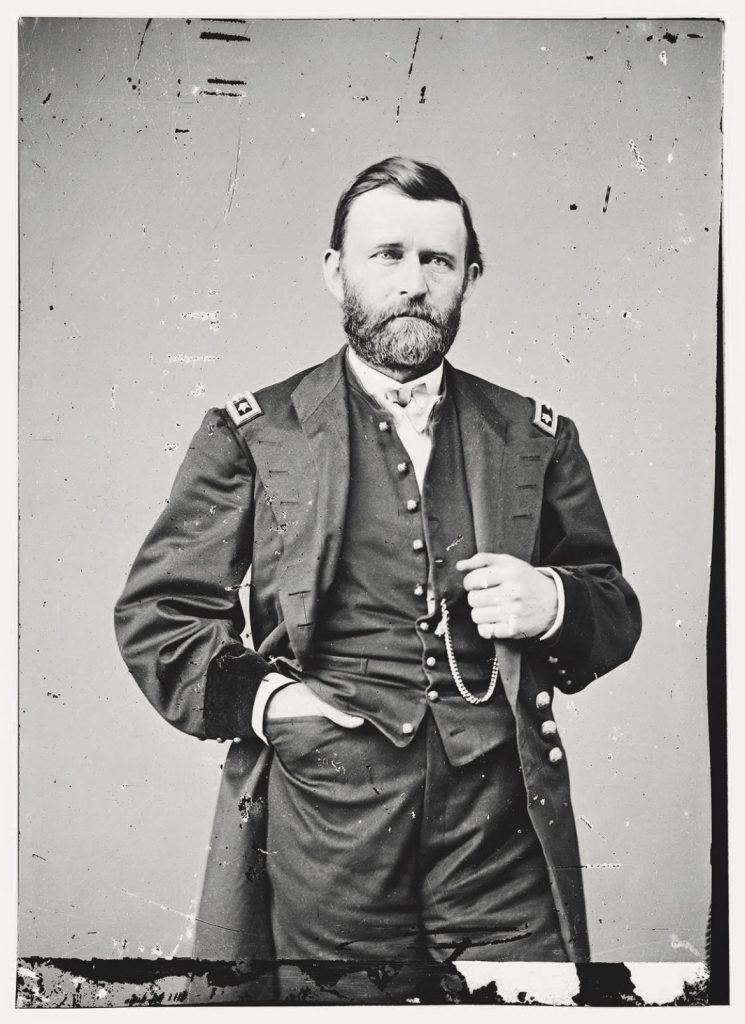

Ulysses S. Grant

In his inaugural address, Ulysses S. Grant pledged to do right by Native Americans.

“The proper treatment of the original inhabitants of this land — the Indians — (is) one deserving of careful study,” he said. “I will favor any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship.”

Grant made good on his promise early in his presidency. Shortly after taking office, he appointed Ely Parker, a Seneca Indian, as commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker, who had served as a lieutenant colonel under Grant during the Civil War, was the first Native American to hold that post.

Grant also introduced an “Indian Peace Policy,” replacing corrupt agents from the Indian Bureau with Christian missionaries and establishing a Board of Indian Commissioners. But even as Grant worked to reform federal agencies, he also supervised the development of millions of acres of federal land and presided over the private acquisition of land by railroad and mining companies.

During his eight years in office, Grant approved the Timber Culture Act (granting homesteaders additional acreage if they agreed to plant trees), the General Mining Act (authorizing prospecting and mining for minerals on public lands), and the Desert Land Act (issuing arid Western lands to individuals who agreed to reclaim and irrigate).

His worst grievance, however, was calling Indians “wards of the nation” and advocating for their assimilation into white culture. Grant’s solution to the “Indian problem” was to relocate them to reservations. Only then, he believed, could white settlers and Indian nations live in peace.

“No matter what ought to be the relations between such settlements and the aborigines, the fact is that they do not harmonize well, and one or the other has to give way in the end,” he told Congress in December 1869. “I see no substitute for such a system, except in placing all the Indians on large reservations, as rapidly as it can be done, and giving them absolute protection there.”

Theodore Roosevelt

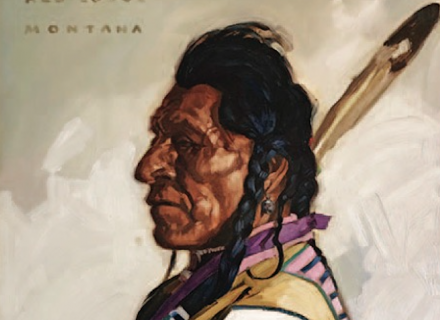

In Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 inaugural parade, six Indian chiefs in headdresses on horseback — including the famed warriors Quanah Parker (Comanche) and Geronimo (Apache) — rode through the streets of Washington, D.C. Though the president applauded and doffed his hat as they passed by, it was an era of tension between settlers and Native Americans over resources, a period when boarding schools for Native children intended to “Kill the Indian, save the man.” The chiefs came hoping to advance negotiations with the president on behalf of their people. Roosevelt wanted to “give the people a good show.”

An early convert to social Darwinism, he believed that frontier life transformed settlers into superior beings and that the “red Indians” would disappear completely. His four-volume The Winning of the West laid out the history of expansionism and the triumph of “civilization” over “savagery.”

Dunbar-Ortiz finds a dark undercurrent in Roosevelt’s protection of millions of acres of public land and his signing of the 1906 Antiquities Act, which granted him authority to proclaim historic landmarks as national monuments. Though the sweeping policy and legislation earned Roosevelt the title “the conservation president,” Dunbar-Ortiz says conservation did little to help Native people: “Roosevelt targeted the most sacred lands of Native Americans. He knew Yosemite and Yellowstone were the spiritual centers of particular Native nations, and those had to be taken in order to destroy the life force of Native people.”

Calvin Coolidge

A black-and-white photograph of Calvin Coolidge posing with four tribal leaders outside the White House in 1924 has come to symbolize one of the most celebrated moments in the federal government’s relationship with Native Americans.

On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted automatic citizenship to “all noncitizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States.” Also known as the Snyder Act, the bill sought to reward Indians for service to their country while also assimilating them into mainstream American society.

Coolidge also oversaw an in-depth investigation of life on Indian reservations — a study funded by John D. Rockefeller and headed by social scientist Lewis Meriam that spanned eight months and included visits to more than 90 reservations. Published in 1928, the Meriam Report described “deplorable conditions” on reservations.

“An overwhelming majority of the Indians were poor — even extremely poor,” the report states. “They are not adjusted to the economic and social system of the dominant white civilization.” The report goes on to detail alarming disease and mortality rates, crowded schools, and startling poverty. Nearly half of all Indians survived on a per capita income between $100 and $200 per year while the national average was $1,300.

Although he sympathized with Native Americans, Coolidge’s solution lacked vision. In his final message to Congress, he advocated for the safe termination of federal oversight and “complete participation by the Indian in our economic life.”

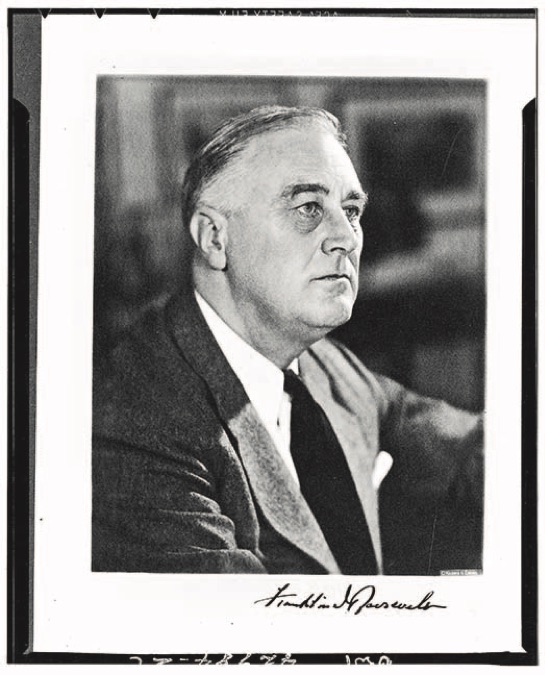

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

When FDR introduced his New Deal in 1933, he also established the Public Works Administration and pumped billions of dollars into the construction of large-scale projects like dams, bridges, airports, hospitals, and schools.

The PWA stabilized the economy and fortified America with concrete and steel. It also displaced thousands of Native Americans and destroyed their cultural histories or livelihoods, says Indigenous scholar and author of As Long As Grass Grows Dina Gilio-Whitaker. This was especially true in the Pacific Northwest, she says, where the government flooded Indigenous homelands to make room for dams.

The grand story of “American progress” celebrates the “genius of American engineering with its railroads and dams, its winning of the West, its conquering of nature,” Gilio-Whitaker says. “There were ideologies that drove presidents to do all these things, but it was really a time of profound death and destruction for Indian Country.”

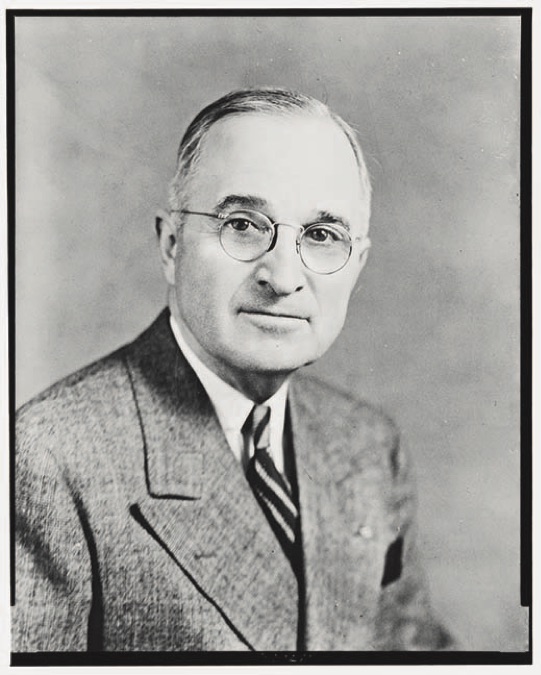

Harry S. Truman

FDR died of a brain hemorrhage in April 1945, just three months after beginning his fourth term. His vice president, Harry S. Truman, completed the term — and quickly introduced sweeping policies designed to terminate federal trust relationships with tribes.

Billed as vehicles to integrate Indians into mainstream society, his termination policies dismantled trust relationships, relocated Indians to urban centers, and stripped tribes of land and sovereignty. Within the first decade of what is known as the “Termination Era,” the federal government ended its relationships with more than 100 tribes, severing tribes’ rights to land, sovereignty, and special protections.

One of Truman’s administrative assistants later criticized Truman’s Indian strategies. Philleo Nash, who served as commissioner of Indian Affairs under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, did a series of interviews in the late 1960s. “At the end of the Truman administration, the Indian people were worse off than they were at the beginning,” Nash said in 1967. Truman’s solution was “to wipe out the reservations and scatter the Indians and then there won’t be Indian tribes, Indian cultures, or Indian individuals.”

Richard M. Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon is best known for being the only U.S. president to resign from office, but the man forever linked to the Watergate scandal also revolutionized federal Indian policy. In 1970, Nixon delivered a landmark address about Indian affairs to Congress. He presented a new policy of “self-determination without termination.”

“The first Americans — the Indians — are the most deprived and most isolated minority group in our nation,” he said. “On virtually every scale of measurement — employment, income, education, health — the condition of the Indian people ranks at the bottom.”

Nixon unequivocally rejected termination policy, claiming it was based on false premises and its practical results were “clearly harmful.” Instead, he advocated for a special relationship between Indians and the federal government that was based on “solemn obligations.”

“Indians can become independent of federal control without being cut off from federal concern and federal support,” he said, also noting that, “both as a matter of justice and as a matter of enlightened social policy, we must begin to act on the basis of what the Indians themselves have long been telling us. The time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions.”

Although he took office amid rising Native American militancy — during his first term, the American Indian Movement and Red Power activists occupied Alcatraz Island, the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, and the village of Wounded Knee — Nixon advocated for Native rights.

He returned the sacred Blue Lake and 48,000 acres of land in New Mexico to the Taos Pueblo (appropriated by Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 for Carson National Forest); doubled the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ annual budget; transferred 44 million acres of land back to Alaska Natives and compensated them with $962.5 million; and signed 52 legislative measures to support tribal sovereignty.

One of Nixon’s greatest contributions to American Indians, however, came after he left office. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, signed in January 1975, officially reversed Indian termination and authorized government agencies to work directly with tribes. Championed by Nixon, the act was designed to “provide maximum Indian participation in the government and education of the Indian people.”

For more from the presidential package …

Theodore Roosevelt

Presidents and the West

Legislation That Made the West

Presidential Places

Photography: Images courtesy Library of Congress, NSF/Alamy Stock Photo, HUM Historical

From our July 2020 issue.