Thanks to early photographers, we know what the frontier looked like, and thanks to Frances Densmore, we know what it sounded like.

The Densmores were among the first settlers in Red Wing, Minnesota, a small settlement along a far northern stretch of the Mississippi River, where Native Americans and westward-moving pioneers were essentially living side by side. As a young girl, their daughter Frances would lie awake in bed in her family’s frontier cabin, listening to the beating drums of the Dakota tribe from a nearby island. As the rhythmic sounds drifted across the quiet waters into her moonlit room, she was not frightened by them but was instead drawn to them. She would later write that the experience shaped the rest of her life.

Born in 1867, Densmore grew up to tirelessly devote herself to a singular mission: working to preserve historic Native American culture, with a particular focus on the music, by collecting as many original recordings as possible, from authenticated sources and well-credentialed performers she would find through copious amounts of travel and firsthand contact with many tribes in North America. Assisted at times only by her sister Margaret and young Native interpreters, she worked for more than 50 years, from the turn of the century up until the mid-1950s. Before she died in 1957, she had completed thousands of well-documented recordings of unique, original, and historically significant Native American music, using the finest recording equipment available at the time — phonographs that utilized a wax cylinder.

Formally educated in music at Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio, Densmore was essentially self-taught as an ethnologist. In addition to becoming a master recording technician and producer and a highly skilled ethnologist and historian, she was also a frontier photographer, taking her cameras everywhere to capture supporting photographs. Along the way she also accumulated a large collection of Native American artifacts.

During the most productive portion of her career, from 1907 to 1934, Densmore was employed by the Smithsonian Institute’s Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE). In addition to making, cataloging, and documenting the recordings, she also wrote prolifically for them, publishing 20-plus books and more than a hundred articles. All the materials — photos, recordings, documentation, and property — were routinely shipped back to Washington, D.C., and into the capable hands of the BAE at the Smithsonian for archiving.

Many of the performers in Densmore’s recordings were highly placed individuals within Native American communities. She considered her subjects astute observers of human character and behavior. Recognizing that any false intentions would be quickly detected and dismissed, she insisted on not trying to adopt cultural affectations — feigning customs, dress, mannerisms, etc. — in an attempt to find favor and gain acceptance. Densmore universally and unapologetically greeted Native American communities as exactly what she was: a middle-aged Midwestern woman in a long Victorian dress. Take it or leave it, Densmore was there to work.

In their noteworthy volume Travels With Frances Densmore (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), biographers Joan M. Jensen and Michelle Wick Patterson describe personal notations from Densmore’s later years that emphasize her desire to be remembered for her professional accomplishments alone. (She had her personal correspondences destroyed after her death.) She specifically mentions wanting to be recognized as an “expert” and “noted authority” in her field of Native American music.

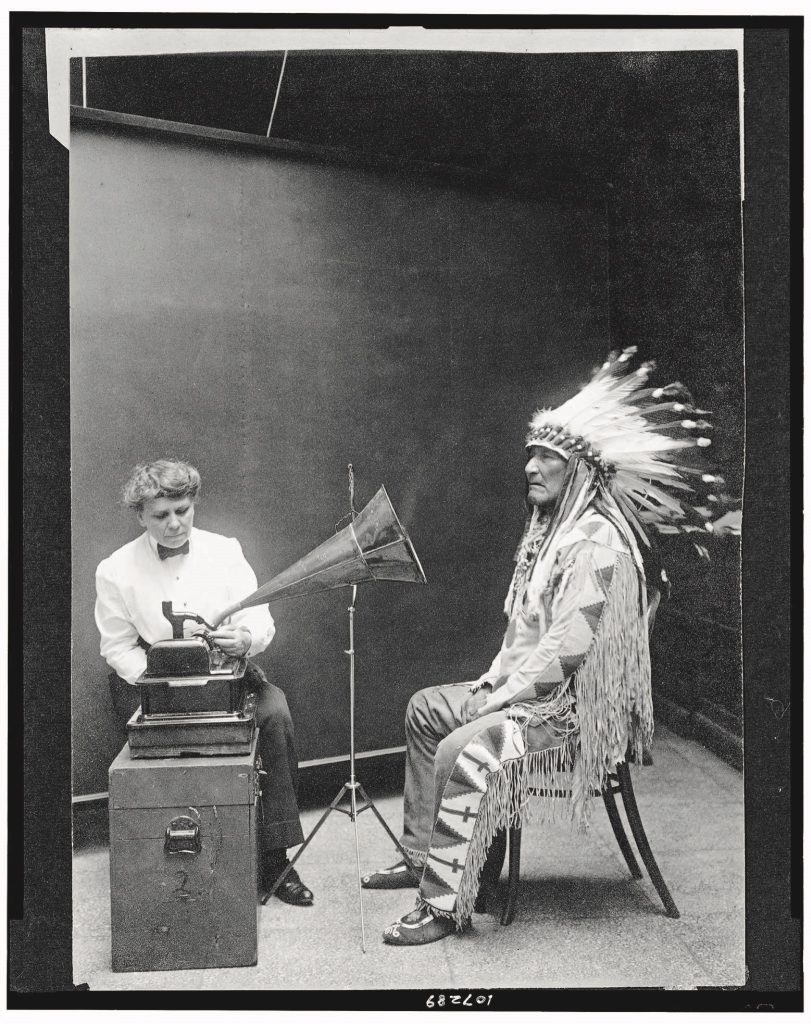

Between 1941 and 1943 she was consultant to the National Archives and established the Smithsonian-Densmore Collection of sound recordings of American Indian music. Today, the bulk of Densmore’s work lies not at the Smithsonian, where it was originally accumulated, but in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, which has digitized many of her recordings. Search under “Frances Densmore” at the Library of Congress site (loc.gov) and among the results you’ll find a transfixing 1916 image (at left) of her sitting next to a cylinder recorder with Piegan Indian Mountain Chief of the Montana Blackfeet, who is listening to a cylinder recording of a song ready to interpret it in sign language to Densmore.

To hear the bygone sounds for yourself, select any of her recordings. Take, say, the mesmerizing cylinder recording of Louis Pigeon singing in the Menominee language a song called “Manabus Tells the Ducks to Shut Their Eyes.” Documented by Densmore in Keshena, Wisconsin, in 1925, it might just transport you to a moonlit night with music wafting on the breeze across the Midwestern frontier.

The Smithsonian Folkways’ collection Healing Songs of the American Indians compiles Densmore’s recordings of medicine men from different tribes singing and chanting songs “delivered to them in dream by external powers and spirits, that they used to heal the sick”; it is available on folkways.si.edu to download or to order as a custom CD.

Photography: Images courtesy Wikimedia Commons, Library of Congress

From our May/June 2020 issue.