As Memorial Day approaches, RW Hampton remembers those who come home and those who don’t.

This evening, as I sit here, I am looking out across our broad valley from this ranch house porch we call home. From here it would seem, I can see from far-distant yesterday clear into tomorrow.

We’ve done a lot of living on this place and sometimes at night my mind drifts back through the years. As the sun slips behind the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, I wonder what my oldest son, Cooper Hampton, USMC, is doing right now. Yes, although it’s late evening here, where he’s stationed a half a world away, a new day is dawning.

Cooper, or “Coop” as we call him, grew up a cowboy in America. Although he joined the Marine Corps just out of high school in 2006, Cooper has told me many times that the ranch skills he learned here in his first 18 years have served him well as a weapons platoon sergeant in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For me as “Dad” every deployment seems to get longer and longer. And yet as we wait and pray, I know that, good Lord willing, before long, there will be a homecoming. Yes, a homecoming!

It occurs to me that this is the first time in my life that I can pretty well guess what all Americans are up to. Yes, like me, I can almost bet, you are quarantined and sheltered in place.

It’s easy to feel like this troublesome pandemic is all that’s going on in our world. But no. We all have lives and there’s a whole lot of living going on beyond it.

Heavy on my mind and heart is knowing that Cooper should be returning home from his latest deployment about anytime now. But due to COVID-19, this too must wait. For how long, we just don’t know.

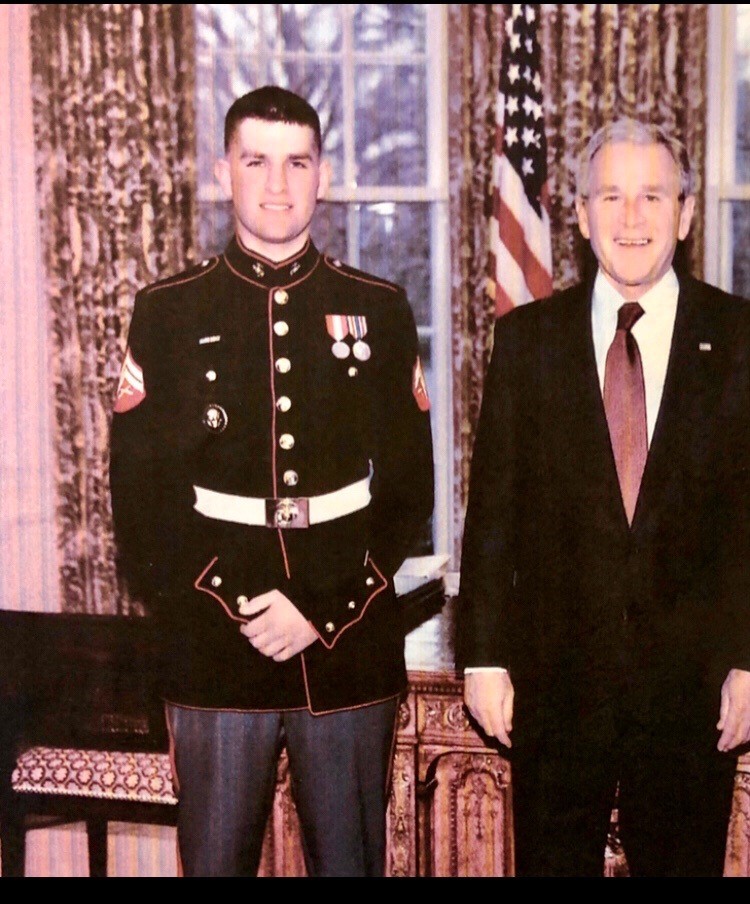

Cooper Hampton with his boss while on Presidential Support Duty

Cooper Hampton with his boss while on Presidential Support Duty

Since Cooper joined the Marines in 2006 I’ve done a lot of waiting — waiting and praying. Here is a story of waiting for a reunion, a reunion I will never forget!

The night of February 10, 2011 found me in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to welcome home the 2nd Battalion 9th Marines from their combat deployment in deadly Marjah, Afghanistan. More specifically, I was waiting for my oldest son, Platoon Sgt. Cooper Hampton of Golf Company. This was Coop’s second deployment, so the waiting was not new, but somehow, with the constant flow of almost-instant information via email and Facebook, the months passed by slow and long.

I had made a conscious decision from the start to be in the know. This meant being familiar with Helmand Province, its people, geography, topography, politics, customs, and even weather. Our clock on the fireplace mantel was set to Marjah time, 10½ hours later than our Mountain Standard Time.

Being informed also meant starting and ending every day checking emails, Facebook, and news reports, trading information and updates with other family members. Even though our boys had no electricity or running water at their FOB (Forward Operating Base), we were able to receive short messages and even photos by virtue of generator-powered laptops.

At times when all communication ceased, we knew we had lost one of our boys and the next of kin were being contacted. Through photos, video clips, and short messages, we knew that our boys were “mixing it up” with the Taliban on an almost-daily basis.

In a strange way our lives and the lives of these young warriors and their families became forever entwined. On some level we, too, had fought and experienced the joys, sorrows, victories, and losses.

Cooper Hampton (standing, upper right) scoping out an enemy position

Cooper Hampton (standing, upper right) scoping out an enemy position

It was all of these things and more that had my heart full and running over that cold, wet night. Along with dozens of others, I crowded into a Marine base gymnasium to wait. The scene could best be described as like a Norman Rockwell painting in which people of all ages carried patriotic banners and balloons. They passed the time visiting, playing bingo and doing crossword puzzles, eating hotdogs, and drinking coffee.

There were grandpas and grandmas, moms and dads, and pretty young women dressed in their finest pushing baby strollers. Charlie Daniels’ music played over an ancient P.A. system that also brought us an occasional update on the status of our loved ones.

We were told that our boys had flown from Germany to the Marine Corps air base at Cherry Point, North Carolina, and were being bused from there to Camp Lejeune. Although I’d never set foot in that gymnasium before, I felt as much at home there as any place I’ve ever been before or since. I felt as if I’d walked into a church social that had no beginning or end, no specific time or location. Just Anywhere, Anytime USA.

The spell was broken when a fella with a strong New England accent walked up and said, “You must be Coop’s dad.”

“You got that right!”

My new Yankee friend explained, “I’m Nate’s dad!”

We visited awhile; then a new update came over the P.A.: Fox and Golf companies were on base. They’d check in their weapons at the armory and be marching in soon. They’d be here in 30 minutes to an hour.

You could feel the level of excitement grow as folks lined up to use the restroom and get one more cup of coffee before going out into the cold, damp North Carolina night. As I refilled my coffee cup, a man beside me, sporting a ball cap that read “Proud Grandfather of a US Marine,” was doctoring his coffee with a little Red Stag whiskey.

“Want some?” he asked.

“You bet!” I said. “If there was ever a night to celebrate, this is it!”

“Amen to that!” was his reply.

I looked at the clock. It was a little after 11 p.m. I got a little nostalgic thinking that almost 24 years ago I was anxiously awaiting my son’s arrival into the world. Now here I was, waiting for that same son, no longer an infant but a hardened combat veteran, to return home from yet another world.

"Coop" on the job in Afghanistan

"Coop" on the job in Afghanistan

Somehow I find that this waiting is just as intense as that first waiting was so long ago. And the questions are the same, too. What will he look like? How will he be? Will he be glad to see me? What will I say? How strange, I thought, these circles life takes us in.

As I looked around I saw that others were dealing with these strange emotions as well, and I was glad we were all going together into the night, where tears of joy and raw emotion could have their way.

I watched as a lovely young woman checked her makeup one last time while another told her three young kids that “Daddy’s on his way!” An older couple readied their balloons; they even had a bottle of champagne to open. I nervously fumbled for my phone to send a quick text to the family back home: “It won’t be long now!”

As folks were making their final preparations, it occurred to me this scene was as old as time itself. Many, if not most, had had long, hard trips to get to this place. All had been waiting for hours, but no one was complaining, just counting down the moments, the seconds!

This scene has played out for as long as men and women have gone to war.

My thoughts were interrupted when a woman at the gym entrance calmly but urgently announced, “They’re coming!”

All talking stopped as everyone headed for the door and out into the night. It was pitch black, but almost as if by instinct people lined up around the edges of the cold, wet parade ground. Not a word was spoken and not a sound could be heard but that of marching boots as they got louder and louder.

My eyes strained to see in the blackness. Then, like ghosts, the silhouettes of men got closer. In perfect formation, they halted in front of the waiting crowd, faceless and unidentifiable, yet only an arm’s length away. Time and breathing seemed to have stopped as one lone voice said, “At ease, men. Well done and welcome home. You are dismissed!”

The waiting crowd started making their way forward to find their loved ones. Some called out names, while others held up cell phones to see. As I waded into the crowd to start my search, I could faintly make out forms as they reunited and quietly slipped away. In the shadows I could see couples locked in embrace, oblivious to their surroundings, as if they were earth’s only inhabitants. I saw tall, straight, young fighting men holding tiny babies for the first time, and whole families holding each other, laughing, crying, as if one. I could hear children crying “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy!” I felt almost as if I was on holy ground as I wandered through these scenes looking for my son.

“Cooper, Coop, Sergeant Hampton!” I called over and over, each time a little louder until a faceless voice said, “He’s in here somewhere, Sir. Just saw him.”

“Thanks,” I said as I wandered on. Finally I stopped and stood just inches away from a silhouette I knew that I knew. After what seemed like forever, a strong voice said, “Dad!” and my not so strong reply, “Coop, oh Son, my son, you big, beautiful son of a bitch, God bless ya! Welcome home!”

I held his face in my hands, making sure this was not a dream. We hugged as men do, laughed, cried, slapped each other on the back — afraid to turn loose, as if this was not real and would all go away.

The circle was complete.

The Playlist

“For the Freedom”

“Hell in a Helmet (Ballad of the 2/9)”

“My Country's Not for Sale”

“The Ballad of Ira Hayes” (Johnny Cash performance)

All the songs on the playlist are performed and written by RW Hampton except “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” which was written by Peter LaFarge.

For more Cimarron Sounds …

Photography: Images courtesy LC Media