Hundreds of thousands of ransacked Native American artifacts sit in museums and private collections throughout the world, while efforts to return them are often rebuffed in the name of science or preservation.

Nobody knows for sure what Johan Adrian Jacobsen was thinking at the time, but he doesn’t seem to have had any qualms about disturbing the dead. Jacobsen was a Norwegian adventurer enlisted by a German museum in the early 1880s to explore Alaska. His task was to find — and take — as many authentic Native cultural items as he could lay his hands on.

In one incident, he opened a grave and discovered the remains of a mother and child. Though their bodies were so fragile they disintegrated the moment he touched them, he was able to retrieve the mother’s skull. After that, he upturned the nearby cradleboard, jostled free the remnants of the baby’s body, and took the cradle, too.

Through purchasing, trading, and unabashed grave robbery, Jacobsen came into possession of more than 7,000 Native artifacts during his journey through Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. And he kept detailed accounts. In his travelogue, published as Alaskan Voyage 1881–1883, he discusses the subject of desecration with casual indifference.

“ ... [W]e went to an old cemetery near Koskimo,” he writes, “where we got three exquisite deformed skulls to rescue them for scientific purposes.”

The plunder of Native American remains and cultural items has transpired since explorers first arrived on the continent, and it was widespread in Jacobsen’s time. Legislation passed during the 1970s and 1980s sought to reverse previous policies and help protect tribes’ cultural traditions, but often didn’t address the hundreds of thousands of artifacts that had been stolen and strewn across the world.

Shannon Keller O’Loughlin, executive director and attorney of the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA), has a long history of working to help protect Native American sovereignty and culture. She says the AAIA has been involved with every piece of repatriation-related legislation, including the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), since its establishment in 1922.

“What pushed this movement forward was the crippling understanding of how many Native bodies have been taken and stored in boxes all over the country — and all over the world,” O’Loughlin says.

Under NAGPRA, federally funded institutions are required to return Native American cultural items. In addition to human remains and burial belongings, the AAIA seeks to help tribes recover religious items, which O’Loughlin says can be equated to materials that might be used during a Catholic or Jewish ceremony, and items of cultural patrimony. Reclaiming these artifacts, though, is a time-consuming and difficult task. To start, there’s no way to know exactly how many of these objects exist. Tribes also face pushback from museums who argue that keeping items on their shelves serves the public. Though other laws may apply, NAGPRA doesn’t extend to private collections or antiques dealers who seek to profit from Native items.

“There are a lot of things that tribes are doing to correct the historic trauma that continues to occur every time we go into a museum or a university or see an auction online, where our items are,” O’Loughlin says. “It’s a reinforcement of those archaic notions that Indigenous peoples are less than, and don’t have a right to their own cultures and values.”

Explorers such as Jacobsen further complicated tribes’ modern-day difficulties by dispersing cultural artifacts far and wide. In many cases, diplomacy is the best, if not the only, way to achieve repatriation — especially abroad, where NAGPRA doesn’t apply. That’s exactly the route that John F.C. Johnson, vice president of cultural resources at Chugach Alaska Corporation, embarked upon after finding familiar descriptions of plundered items in Jacobsen’s grisly travelogue.

These, he suspected, were items that rightfully belonged to the Chugach — Alaska natives who have lived near Prince William Sound for thousands of years. Johnson’s prior investigations have led to the retrieval of human remains and artifacts in the United States and abroad. The return of long-lost items is sort of like finding the missing pieces of a puzzle.

“A lot of these things have a real strong religious and spiritual meaning,” Johnson told CNN in 2018. “This will help to teach the younger generation and help keep our culture alive and intact.”

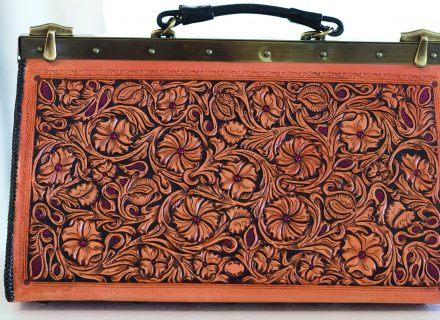

In 2015, Johnson and a Chugach delegation visited the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin to initiate cooperation on a project that would create a virtual gallery of tribal artifacts. During the visit, Johnson identified objects that he believed had been stolen from the Chugach. These included two ancient wooden masks. One was topped with a sharp point, an indicator of a soul’s passage to the underworld. The other featured a face with one eye closed and one eye open. Also among the items were a wooden idol and a baby’s cradleboard — likely the very same one Jacobsen pulled from the grave of the mother and child.

O’Loughlin has seen her fair share of repatriation cases, too. One notable example happened in 2009, when prominent art dealer Sotheby’s put two ceremonial wampum belts up for sale in an art auction. The belts, estimated to have been made between 1760 and 1820, had previously been showcased at the predecessor to the National Museum of the American Indian.

“Wampum belts are known to be objects of cultural patrimony, and they’re known to be held communally by a tribal nation,” O’Loughlin says. “They provide important governance information and contain spiritual information and other messages that tribal leaders are able to decode.”

After intervention from the Onondaga Nation, for whom O’Loughlin served as a lawyer, the items were pulled from the auction. They were part of a private collection, though, and it took more than eight years before the belts were repatriated.

“Some of this is just waiting for people to die,” she says, “but really, people who are involved in museum curation today — most of them are growing up understanding NAGPRA and the importance of cultural heritage.”

In the case of the plundered Chugach items, the effort to have them returned took three years and included a diplomatic plea from the U.S. government and an investigation by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Finally, in May 2018, Johnson returned to Berlin. He donned white gloves and stood alongside Hermann Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Parzinger carefully handed Johnson the mask with the pointed top, and Johnson held it gingerly, smiling, as cameras flashed around him. The masks, the idol figure, the baby’s cradle — they were finally going home.

Jacobsen’s travelogues help us understand the prevailing mentality of his time. Today, though, there are still individuals and institutions who cling to Native items in an effort to “preserve” them, and this resistance to cooperation actually prevents a better overall understanding of them. O’Loughlin says that sometimes it’s as though people forget that Native Americans exist today — and that tribes themselves are the ones who best understand the cultural significance of their own items.

The national NAGPRA program estimates that more than 50,000 ancestors’ remains and more than a million artifacts have been repatriated since the passage of NAGPRA. However, there are countless missing pieces scattered across the world — including the mother’s skull that Jacobsen took from the Chugach grave. The return of items like the ceremonial masks and wampum belts are a step toward righting ancient and modern wrongs, but there’s still much to do.

“Very deep experiences and relationships are built when institutions, individuals, or collectors work with tribes,” O’Loughlin says. “It’s healing on both sides, and a resolution. I’ve only heard good stories about when repatriation occurs.”

Photography: Courtesy Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Martin Franken, 2018

From the August/September 2019 issue