Where does opera meet the Wild West? In the Gold Rush-era La fanciulla del West, which had its guns-blazing world premiere in New York 108 years ago and is on the stage again there this October.

On Wednesday, November 16, 1910, the famed Italian composer Giacomo Puccini, 51, walked down the long gangplank that stretched from the German-built luxury ocean liner SS George Washington onto the shores of New York.

The world premiere of his latest opera, The Girl of the Golden West, which, like the megahit before it, Madama Butterfly, was based on a popular play by American David Belasco, would be performed for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera House at 39th Street and Broadway in a few weeks. Its three tiers of private boxes arranged in a horseshoe shape would likely be filled with Roosevelts, Vanderbilts, Astors, and sitting squarely in the center in box 35 — the space reserved for royalty in European theaters — the J.P. Morgans.

It had been a tumultuous year leading up to the premiere performance of the first Puccini opera to have its world debut in America. In the Tuscan village of Torre del Lago, where he lived with his wife, Elvira, and their son, Antonio, Puccini’s young maid had committed suicide after his wife accused her of having an affair with her husband (an autopsy soon revealed she was, in fact, a virgin). Elvira was sent to prison for slander, but Puccini paid the girl’s family a considerable sum to drop the charges. By all accounts, the emotional turmoil took a heavy toll. Puccini was reported to have been suicidal — not surprising since he had admittedly suffered from depression his entire life.

With superstars tenor Enrico Caruso and soprano Emmy Destinn playing the two lead roles, it was an opening night anticipated like no other. The hall was hung with Italian and American flags. Scalpers bought and sold tickets for as much as $75 the day before, but the street price dropped to a more reasonable $18 within hours of the show at around 8:30 p.m.

The applause was quick and constant. The audience had to be hushed several times so the orchestra and performers could be heard. Some women clapped so vigorously that they split their gloves. By the end of the first act, there were 14 curtain calls — Puccini appeared for two, along with Belasco, and Arturo Toscanini, the Met’s famed conductor, who called the opera “a great symphonic poem.”

“My heart is beating like the double basses in the card scene,” Puccini exclaimed. “I am tremendously pleased with this reception. I couldn’t have better interpreters for my work,” The New York Times reported.

By all accounts, La fanciulla del West, as it is called in Italian, was a huge success — at least on opening night.

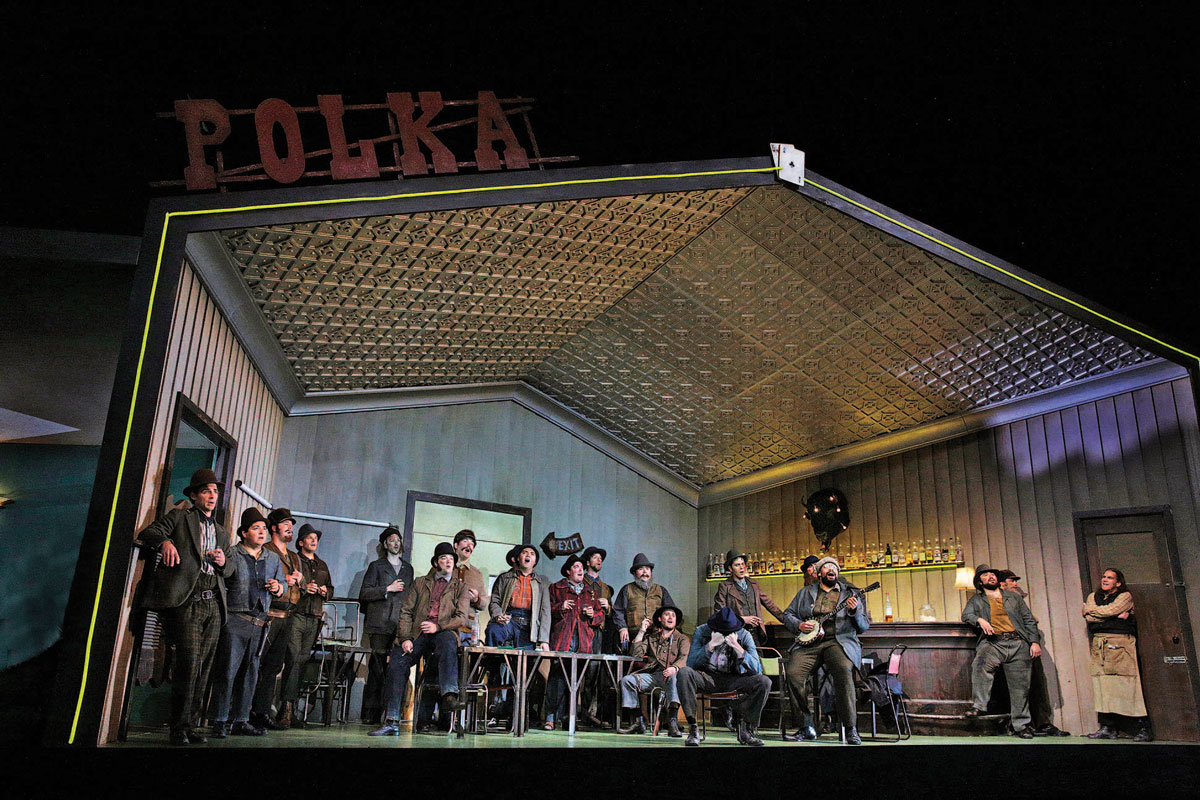

Photography: (TOP) Enrico Caruso as Dick Johnson, Emmy Destinn as Minnie, and Pasquale Amato as Jack Rance in the final scene of Puccini’s western opera, La fanciulla del West, which premiered at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1910/ Courtesy The Metropolitan Opera Archives. (ABOVE) The Polka Saloon in the 2016 plein air production of Puccini’s California Gold Rush-era spaghetti western at the Santa Fe Opera/Courtesy Santa Fe Opera.

Puccini continued to rewrite the score, as he was known to do, seven more times. But in the end, it didn’t matter. While the opera became a hit in Germany, in the United States the initial enthusiasm of audiences quickly waned and opera critics panned the work overall. They continue to do so today, reducing it to “a musicalized play” and a “spaghetti western.”

The libretto, a mixed bag of Italian peppered with English (“Whiskey per tutti!” and frequent cries of “Hello!”), has been called absurd, and the tale of a bandit who falls for a pistol-packing saloonkeeper named Minnie, who saves him from death before they ride off together, has been accused of being corny, naive, and unbelievable. So much for simple love stories. Perhaps more than any other opera, Puccini’s Girl of the Golden West begs the question: Is an opera without a predictable, tragic aria-accompanied murder or suicide end doomed?

Today, Fanciulla might be performed once a year at an opera company somewhere in the United States, whereas Madama Butterfly, a perennial favorite and dependable ticket seller, is probably on stage 30 times or so.

There is only one true aria in Fanciulla — “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano” in the third act — which may also be why today’s audiences shy away from it. People expect recitatives, arias, duets, and choruses. They know when to clap and understand when not to. But Fanciulla isn’t like any other opera. A complete departure from 19th-century Italian opera conventions with their predictable stops and starts and formal patterns of sequencing, nothing like it had been heard before.

“It’s a powerful piece,” says Emmanuel Villaume, music director of the Dallas Opera, who conducted Fanciulla at the Santa Fe Opera in the 2016 season. “It’s the last period of Puccini and he’s experimenting with rhythms — harmonies shifting and moving quickly, rhythms that are intricate, and a sense of color and space and visual expression of music through orchestration and lines that are absolutely mind-blowing.”

The subject matter — leaving home to mine for gold in California — gave Puccini one thread to work with, of loneliness and longing. The grand spaciousness of California and the hope of striking it rich, another. The seemingly simple, yet never so, conflict of love versus money. Friendship. Jealousy. All themes seamlessly stitched together musically in a score that rises, falls, expands, and contracts with precision and swift movement, galloping madly from one scene to the next. It’s a tightly constructed piece that grabs you, takes off, and doesn’t let go until the end. When it’s over, you’re left sitting at your seat with your program in your lap, wanting to hit replay. And it does replay — bits and pieces of tunes keep playing in your head for days and weeks afterward.

“[Puccini] was a genius at knowing what hits that sort of internal resonance we all have,” says tenor Gwyn Hughes Jones, who played Dick Johnson, the lead, in the Santa Fe Opera production. “When I listen to his music, even if I’ve never heard it before, it’s as if I’ve always known it. It shows a great understanding of human nature and the brain and our psyche to understand what hits that internal note.”

Puccini found inspiration in the music featured in Belasco’s play — polkas, waltzes, and ragtime — plus added some of his own. The not-quite-an-aria melody in the first act, “Che faranno i vecchi miei,” is based on a Zuni sun dance, and can be heard in different tonalities and rhythms nearly a dozen more times throughout the score, appearing like so many musical ghosts — as soon as you recognize what you’re hearing, they disappear. (Which is perhaps why Andrew Lloyd Webber borrowed the terribly catchy melody behind “Quello che tacete” in Act I for his hit musical The Phantom of the Opera. In Phantom, the same tune is behind “Music of the Night.” The Puccini estate sued; the matter was settled out of court.)

This subtle imprint of recurring melodies is part of what makes Fanciulla texturally rich and modern for its time, says Villaume, but there are other aspects that add to the opera’s complexity.

Openness in the score itself, with instruments pushed beyond their usual limits — piccolos are tuned higher; double basses lower — and rhythmic meters stretched, some well past 12 beats per bar. “They are Texas-size,” says Villaume. “The way he’s cutting the music is larger, to express the notion of vast open space and as a metaphor for open land where everything is possible.”

From the explosive, cannonlike boom-boom-boom of the timpani and brass drums followed by the steely crash of the cymbals, you’re hooked. The story hasn’t yet begun, but already it feels and sounds so familiar, this tale of love that strikes hard and fast and opens our hearts, set against the grand expanse and wide open spaces of the American West.

“What’s fascinating is this is before the western [movie] was invented,” Villaume says. The first western, The Great Train Robbery, came out in 1903, but it was silent; the first talkie western, In Old Arizona, in which star Warner Baxter does some incidental singing, wouldn’t come out till 1929. For his 1910 opera, Villaume says, “Puccini created a sound that was very new and instrumental in defining what would be, in the American iconic memory, the sound of the West, and the sound that will later appear in western movie music.”

Puccini wrote the score for Fanciulla without having visited California or the American West. And yet his musical language so fluently described the sense of place that it has become symbolically authentic.

Told in three acts, Fanciulla opens at the Polka Saloon, where gold-panning miners can always find plenty of whiskey. Everyone who comes to the Polka seems to have a crush on the gun-toting, Bible-quoting, never-been-kissed saloon owner, Minnie, who might just be the forerunner of Gunsmoke’s Miss Kitty. That’s especially true for the sheriff, who from the moment he appears on stage makes it clear that he feels he is most deserving of her attentions, despite the fact that she has no interest in him.

All it takes is a charming bandit who goes by Dick Johnson (or Ramerrez, depending on the company he’s in) to turn Minnie’s head. And so the story is set in motion, one of love at first sight, of romantic first dances and flirting (in the first act, Johnson wonders aloud to Minnie whether men ever try to steal the gold — or to steal a kiss), followed by jealousy (the sheriff’s), and attempts at revenge. The opera moves quickly, blockbuster-movie style, from the beginning to its redemptive end, where Minnie begs the miners to spare the life of her one great love, reminding them of the kindness that she has shown them all, and asking for the same in return.

Puccini loved women — among others, he was said to have had an affair with the soprano Emmy Destinn — and he loved putting them in strong roles. The independent, self-sufficient Minnie leaves no question about who’s the toughest character among the posse of miners. She can cheat (and win) at cards and shoot a gun, yet still fall head over heels for an already-married rogue with a kind heart — making her vulnerable, likeable, and completely believable. We’re rooting for her from the start.

After the monsoon rains drifted north on a cool Tuesday night in August, at the end of the 2-hour and 43-minute-long performance at the Santa Fe Opera, there were three exuberant curtain calls, with conductor Villaume in the middle, leading the cast in full bows, his hands clasped with Patricia Racette, who played Minnie, on his left, and Gwyn Hughes Jones, who played Dick Johnson, on his right. The audience gave a standing ovation. They clapped until the stage went dark.

However the reviews published a few days later were not altogether kind. The sets were too cramped for the stage, one reviewer said. The orchestra overwhelmed the singers, said another. The Italian-English libretto, problematic. Ticket sales remained steady but didn’t quite meet expectations. “I was on one level disappointed, but you have to stick to your guns and what you believe, and I think this is first-rate Puccini and I think it is underrated Puccini,” said Charles MacKay, who was Santa Fe Opera general director at the time.

La fanciulla del West is considered by many academics and musicologists to be Puccini’s finest work. French composer Maurice Ravel so regarded the piece that he used it as a teaching tool for his students at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. Puccini said it was the best opera he had ever written.

La fanciulla del West premieres at the Metropolitan Opera House, Thursday, October 4, and runs through Saturday, October 27. Tickets can be purchased at the Met’s website. Read more about the opera in The Met Goes West — Again, by Dana Joseph.