One hundred years ago, one of country music’s most popular and influential singers was born. So why isn’t he better remembered now?

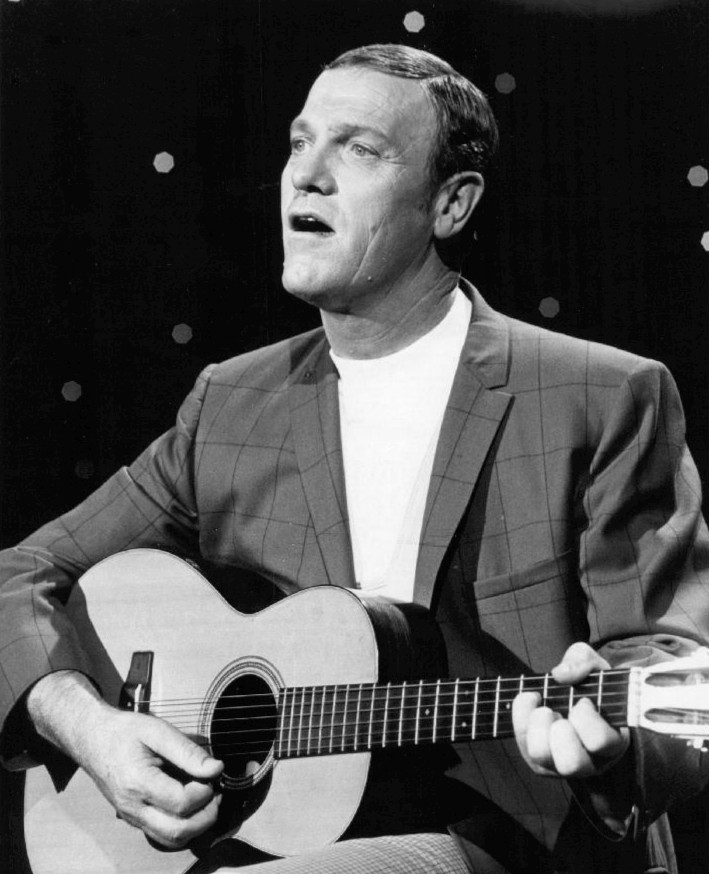

The name Eddy Arnold will inspire an instant smile among country music fans of a certain age. From the 1940s through the 1960s he was a mainstay in the Top 10, an in-demand performer on concert stages from the Grand Ole Opry to Carnegie Hall, and a frequent guest on television variety shows, as well as the host of his own series.

But unlike many of his contemporaries — Hank Williams and Patsy Cline, George Jones, and Loretta Lynn — whose names are still familiar to today’s country fans, Eddy Arnold’s legacy has not maintained the same reverence.

His accolades still speak for themselves: 85 million records sold, and 147 songs on the Billboard country music charts, second only to George Jones. When he sold his 50 millionth record in 1967, it was an achievement equaled only by Bing Crosby, Elvis Presley, and The Beatles. His songs spent a total of 145 weeks in the No. 1 position on the country chart — more than any other artist in history.

“He was an honored statesman in his last few years, but it didn’t carry like some of the others,” says Don Cusic, a friend of Arnold’s and the author of the biography Eddy Arnold: His Life and Times. “He never got to be cool like Johnny Cash.”

Another reason may have been Arnold’s decision to change his sound in the 1950s, hoping to broaden his appeal by putting out records that were more pop than country. “It made him popular in the middle class, but he was almost viewed as a sellout,” Cusic believes. “That might have hurt him as well in terms of longevity.”

From Plowboy to Cowboy

While Arnold’s “Tennessee Plowboy” nickname didn’t fit the debonair artist he aspired to be and ultimately became, Richard Edward Arnold came by it honestly, having spent the Depression years behind a mule and a plow.

Soon after he was born on May 15, 1918, in Chester County, Tennessee, his family was reduced to being sharecroppers on the farm they used to own. Arnold learned to play guitar from his mother and quit school at 16 to become a singer. He succeeded through hard work and steady advancement, first as a member of the Golden West Cowboys, and then as a solo artist.

In 1944 he recorded “Cattle Call,” the song that would become his signature. That same year he met Col. Tom Parker, a master promoter (as Elvis Presley would later discover) who became his manager. In 1946, Arnold co-wrote and released “That’s How Much I Love You,” which went to No. 2 and established him as a nationally known recording artist.

Thus began a decade of chart dominance that reflected not just Arnold’s talent but his sharp business instincts. In 1942, the start of his recording career had been delayed by a musician’s strike. In 1947, with another strike looming, Arnold went into the studio and recorded 25 songs in three days. When the strike hit, he had a stockpile of new material ready to be released. “I’ll Hold You in My Heart” reigned at No. 1 for 21 weeks. The follow-up, “Bouquet of Roses,” spent 54 weeks on the country music chart — a record that stood until 2010.

This wasn’t the only time Eddy Arnold was ahead of the show-business curve: He played Las Vegas in 1948, just two years after Bugsy Siegel opened The Flamingo, and he made his television debut in 1949, when the medium was still considered a novelty, on The Milton Berle Show. But he turned down an offer to become a singing cowboy in the movies like one of his early heroes, Gene Autry.

From Cowboy to Crooner

In 1953 Arnold released “I Really Don’t Want to Know,” a No. 1 record that introduced his more sophisticated sound. Lush strings replaced the steel guitar, and Arnold’s rich tenor voice became a smooth baritone. Also gone were his cowboy boots and jeans, traded for sport coats or tuxedos.

“I was talking to him about the 1940s, when he was really dominant, and he kept saying, ‘Well, what about the 1960s?’ because he always wanted to be Bing Crosby,” says Cusic, reflecting on the interviews he did with Arnold for his book. “He was always most proud of “Make the World Go Away” and all those other big hits.”

In fact, Arnold was so fond of those singles — forerunners of what would become known as “The Nashville Sound” — that he would record new versions of many of his early hits, including “Cattle Call” and “Anytime.” Working with producer Chet Atkins and an orchestra led by Hugo Winterhalter, Arnold became a staple on both the country and pop charts for the next two decades.

“I wanted to broaden my appeal,” he told one interviewer. “This may make the purists mad, but for every purist I lose, I gain five other fans who like country music the modern way.”

“I tend to like his earlier material,” says Shannon Pollard, Arnold’s grandson. Pollard maintains the Eddy Arnold Facebook page, and is the president of Plowboy Records. “I think his voice was always stunning, especially as he matured, but I have always gravitated towards his pre-1965 songs. People forget how much he did to make it OK for non-country listeners to check out artists they wouldn't have otherwise. He was proud of that part of his legacy. Purists can debate, but it’s undeniable the success of Eddy Arnold helped put Nashville on the map as a major recording hub.”

And even those purists would find it hard to deny the craftsmanship in Arnold’s later work. “He had an integrity with his music. He was serious about the songs that he did. It wasn’t just scraping up 10 to 12 songs for an album,” Cusic says. “He really wanted to get into each song, and to make it a part of him. He spent a lot of time working on his performance.”

Eddy Arnold’s last performance was on May 16, 1998, the day after his 80th birthday. He spent the ensuing 10 years in a happy retirement.

“I was able to go to lunch with him on a regular basis with his buddies — Jerry Reed, Hank Cochrane, and Jerry Chestnut. My grandfather would hold court at his favorite lunch spot. He would tell jokes and laugh so loud it reverberated through out the entire restaurant,” Pollard recalls. “I also enjoyed visiting with him at his office and we would listen to [his] old records. Those were very special moments. Sometimes he’d fall asleep and wake up grinning.”

That doesn’t sound like someone who spent much time worrying about how much attention he was getting. Indeed, even at the heights of his record-selling success, Arnold always expressed surprise when a reporter asked to interview him. Perhaps that’s because he was married to the same woman for 66 years, always signed autographs and answered his fan mail, and never left a hotel room in a shambles or spent a day behind bars.

“It is more interesting if an artist gets drunk, shoots up the town, misses the concert, or staggers through it, and careens self-destructively toward the next event. But for the folks who paid money to see the performer in concert, it’s a waste of time, effort, and money,” Cusic writes in his Arnold biography. “Eddy Arnold always made sure people who paid to see him got their money’s worth.”

And those who saw him certainly do remember.

PLAYLIST

The Essential Eddy Arnold

Here’s a C&I playlist of Eddy Arnold tracks, including some of his most popular hits and a few lesser-known songs beloved by those who knew him best.

“Cattle Call” (1944)

How much did Eddy Arnold love this ethereal Western ballad? He first recorded it in 1944, chose it as the theme song for his radio show, and recorded the song again in 1955 — that version went to No. 1. He cut it for a third time in 1961, and again in 1996 as a duet with LeAnn Rimes. In later years, when he’d finish that wonderful yodeling falsetto chorus, he would often pause and say to the audience, “Didn’t think I could still do it, did you?”

“It’s a Sin” (1947)

Those who may dismiss Arnold as an easy-listening artist would be wise to reconsider after listening to many of his sadly forgotten 1940s recordings, like this No. 1 honky-tonk classic.

“Anytime” (1948)

For a perfect illustration of how Arnold’s recording style evolved, listen to the 1948 version of “Anytime”, which went to No. 1, and then play the 1967 version with its lush strings and smoothed-out tempo.

“Bouquet of Roses” (1948)

One of five No. 1 hits for Arnold in 1948, this heartbreak ballad stayed on the charts for more than a year and almost became his first crossover pop hit.

“Will Santy Come to Shantytown” (1949)

“This sounds nuts,” Shannon Pollard admits about this favorite from his grandfather’s hundreds of songs, “but it’s because he wrote it about his childhood about being a poor sharecropper kid wondering if Santa will come to his house on Christmas Eve. It’s so sad.”

“I Really Don’t Want to Know” (1953)

This was the song that heralded Arnold’s more sophisticated sound. It went to No. 1, but it also began a rebranding of the artist as too uptown for country and too rural for pop — one reason why you don’t often hear his records on oldies stations from either genre. But by making that change, argues his friend and biographer Don Cusic, Arnold led country music out of its “hillbilly” music phase and into the mainstream of American popular music.

“You Don’t Know Me” (1955)

Arnold received a co-writer credit on this chart-topping classic, though he provided writer Cindy Walker with only the title and its story about unrequited love. It has become a romantic standard, covered by everyone from Ray Charles to Meryl Streep.

“Cowpoke” (1963)

“This is the one I like the best,” says Cusic. “It was written by Stan Jones, the guy who wrote ‘Riders in the Sky.’ He does this yodel in it that was just killer.”

“Make the World Go Away” (1965)

This Hank Cochrane-penned tune was so popular, Arnold took it to No. 1 just one year after Ray Price’s version reached No. 2. This was also Arnold’s highest-ranking song on the pop charts, climbing to No. 6. At the 2008 Academy of Country Music Awards program, Carrie Underwood and Brad Paisley sang the song as a duet to honor Arnold’s legendary career.

“To Life” (2005)

After Arnold’s death in 2008, RCA re-released “To Life” as a single. It spent just one week on the country chart at No. 49, but it gave Arnold the distinction of being the only musical artist in history with a hit song in every decade from the 1940s to the 2000s. It was an eloquent final bow for one of country’s gentlemen.

Photography: Eddie Arnold 1969/Courtesy Wikipedia

More Entertainment

The Rider: Reality Hits Home

Happy Trails To Glen Campbell (1936-2017)

Westworld Gets Early Renewal For Season 3