This award-winning Crow artist uses striking color, audacious humor, and bold imagery to present themes of race and cultural identity — and to show that being authentically Native American is a thriving, evolving thing.

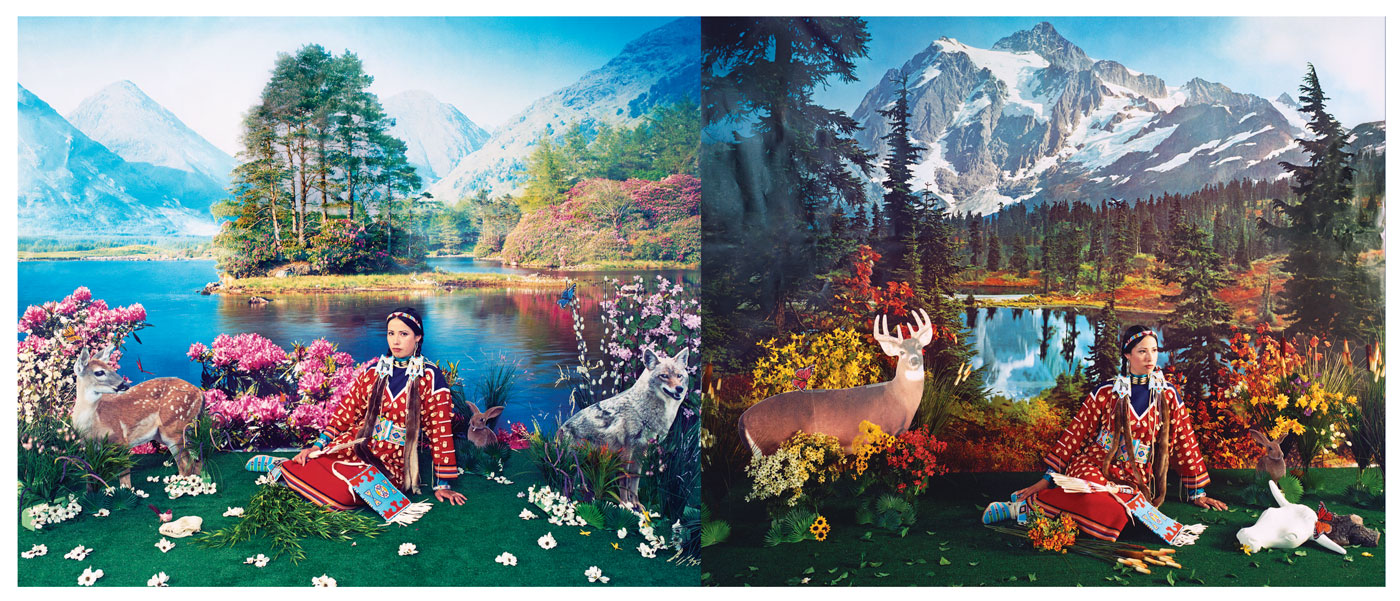

The first thing you notice about Wendy Red Star’s photography is the color. Crazy combinations. Super saturation. An almost hallucinatory vibrancy.

“I was putting together a collection of my work recently and thought, Wow, I really do like colors!” says the 36-year-old Apsáalooke (Crow) artist. “It even stopped me.”

For Red Star, unexpected colors are simply an extension of the culture she grew up with on the Apsáalooke reservation in Montana. Electric pinks, blues, yellows, reds. “Colors that don’t necessarily go together but somehow work — that’s very much part of the Crow palette,” she says.

Although it’s a hallmark of her work these days, audacious color schemes haven’t always gotten Red Star the acclaim that’s come her way over the past decade. As a grad student in fine arts at UCLA, her now-celebrated series Four Seasons — in which Red Star poses in ceremonial dress against a backdrop of faux nature scenes — drew heavy criticism from instructors and peers.

“I was told, ‘These works will never show, they’re not professional enough,’ ” Red Star says, more matter-of-fact than bitter about the memory. “I realize now that [my instructors] were adept with the privileged language of theory and abstraction. But when it came to identity-based art, they didn’t know how to talk about things like race and cultural history.”

Then again, Red Star readily acknowledges she wasn’t the easiest pupil.

“I was a [jerk] as a student,” she says, recalling disregarding assignments to pursue her own vision. That sophomore hardheadedness isn’t hard to imagine. You see defiance of convention in everything she does.

Four Seasons became what Red Star calls her “gate opener.”

“I kept the faith in that work,” she says. “When it showed in [The Metropolitan Museum of Art], my dad flew to New York to see it. It took that level of acceptance for my parents to take this whole art thing seriously.”

Created in 2016, her widely circulated Apsáalooke Feminist series is an extension of that surreal, super-colorful juxtaposition of worlds. In a sort of update on historical Native American photographs, Red Star adopts classic poses with her young daughter on what looks like an Ikea couch. Both are outfitted in resplendent ceremonial dress.

Employing an unapologetic social perspective, Red Star’s work is often hilarious — and autobiographical. The Last Thanks, a 40-by-50-inch photographic print shot with a medium-format camera, depicts a glum-faced Red Star flanked by Native American skeletons at a Thanksgiving meal of Oatmeal Creme Pies, bologna, canned green beans, Kraft Singles, Wonder Bread, and Natural American Spirit cigarettes. “The food on the table was everything I ate when I went to my grandmother’s house as a child,” she explains.

More outrageous is White Squaw. Debuting in 2014 in her current home of Portland, Oregon, the work is a sendup of a series of “adult western” romance novels published in the 1980s and ’90s. Featuring a promiscuous half-Native heroine, the books’ tag lines drip with cringe-worthy sexual double-entendre. Red Star re-created the covers, with photos of herself as the lubricious heroine.

“When I saw those books, it was shocking. I couldn’t leave it alone. I had to do something with it,” she says. “The dark subject matter in my work is healed through humor.”

Look at White Squaw and you might assume a play-with-fire frivolity is the sole driver of Red Star’s work. Sit down with her over coffee, however, and you find a history-obsessed introvert. Red Star’s devotion to research shines through a series of 1880s photographs by C.M. Bell that she annotates with a red marker as part of her arresting exhibition Medicine Crow & the 1880 Crow Peace Delegation. One note on a black-and-white print informs viewers that the body of its Crow subject was eventually stolen and put on display in a museum. Others explain the significance of tribal outfits. An ermine pelt attached to a legging, for instance, meant a warrior had stolen an enemy horse as part of becoming a chief.

“They risked their lives for those outfits. They were showing their power,” not simply submitting to an exercise in ethnographic preservation, she says.

Also a seamstress and designer, Red Star becomes animated when explaining the significance of the Crow elk-tooth dress — wool dresses adorned with the eyeteeth of elk, she calls them the epitome of Crow culture. The more teeth, the more powerful the dress. “Basically it’s a woman showing off the hunting abilities of the men in her family — husbands, fathers, brothers,” she says. That portrayal of strength and pride of culture is also evident in her 2011 series Thunder Up Above. In it she depicts herself in regalia of her own making, part of a sci-fi race of “fierce ambiguous beings” not to be trifled with. For it, she photographed herself in her bedroom, then photo-edited her powerful anonymous image into a futuristic frontier of otherworldly landscapes.

As a look at her packed 2018 calendar illustrates, Red Star is one of the hottest Native American artists of the day, not only as a solo artist but also as a curator of exhibitions. “Institutions are asking me to curate contemporary Native exhibitions,” she says. “To represent these artists is an incredible responsibility.”

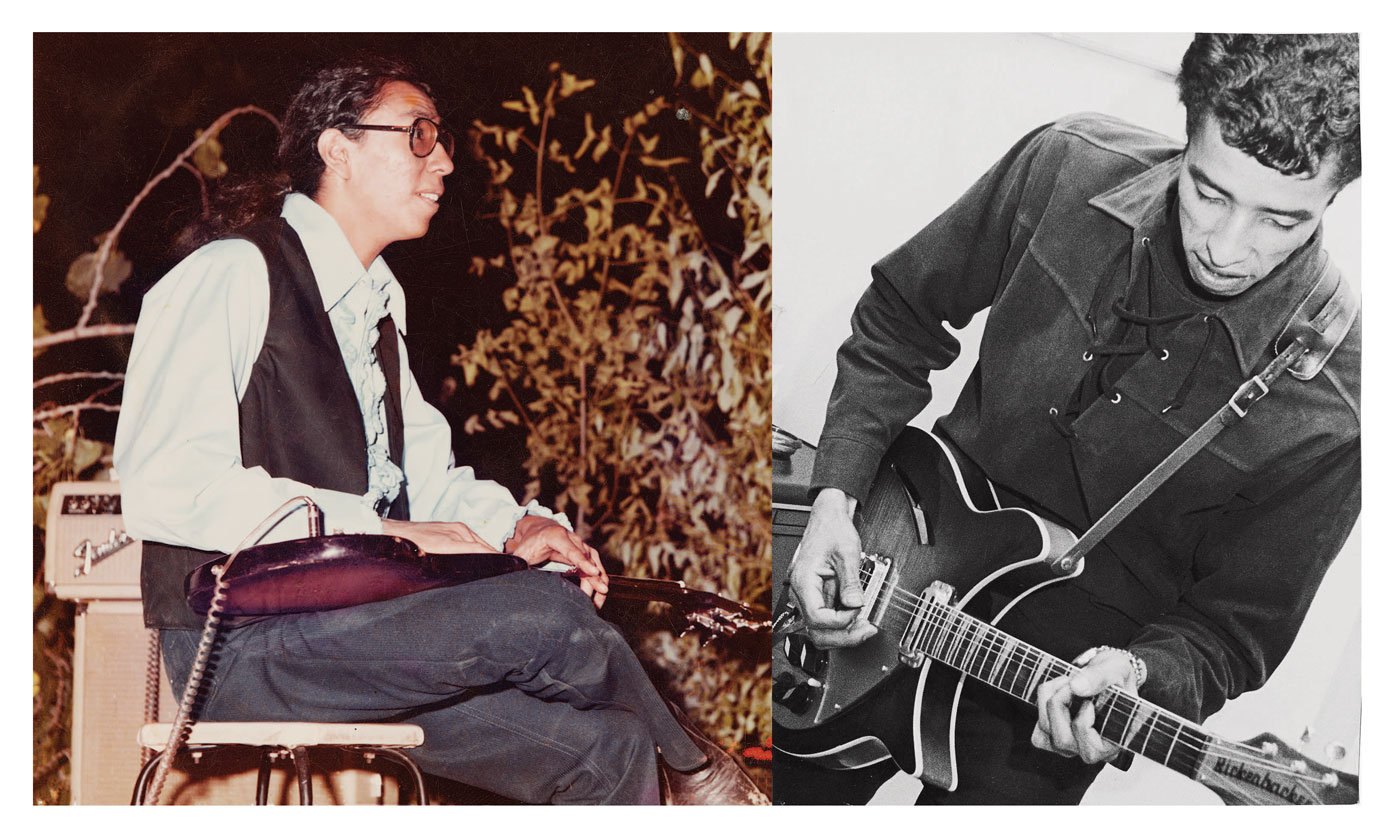

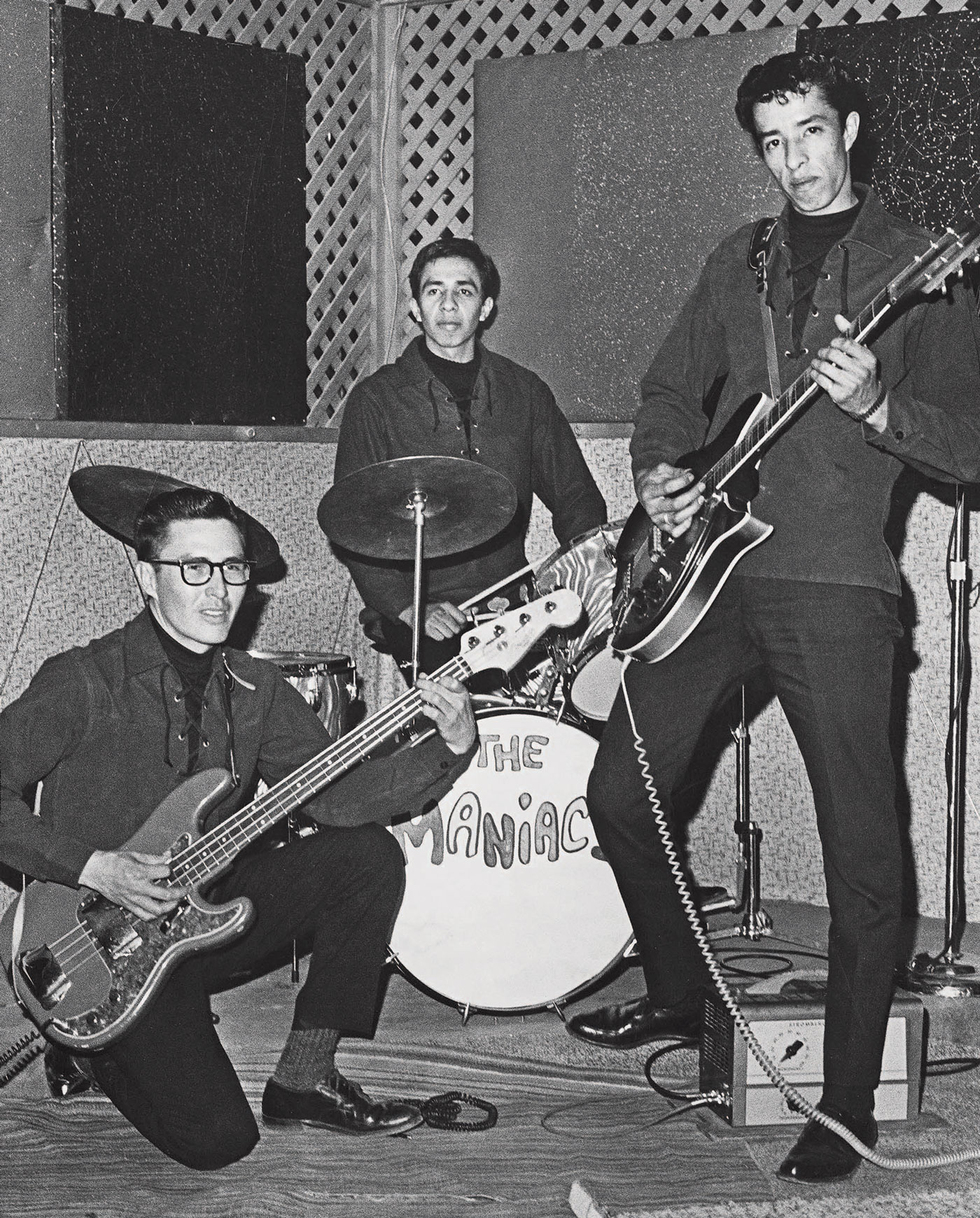

This year, Red Star will travel two or three times a month for museum exhibitions, gallery shows, and lectures. She’s perhaps most excited about a solo showcase at New Mexico State University (January 25 – March 17). Titled The Maniacs, We’re Not the Best But We’re Better Than the Rest, the all-new work is a multimedia timeline of her father’s life based on his music.

A classically trained guitarist who toured with a Native American quartet as a child, Red Star’s father (with whom she remains close) was eventually sent to Vietnam with the U.S. military. There he joined a Marine rock band, The Maniacs. On his return to the Crow Reservation in Montana, he formed another version of The Maniacs with his brother Wendell (Wendy’s namesake) and cousins. The stateside Maniacs became a raucous band with a rabid local following, playing proms, parties, and the reservation’s “round hall,” the Ivan Hoops Memorial Hall. The group reached its apex in 1977 by winning what Red Star calls “a very redneck” battle of the bands in Sheridan, Wyoming, besting dozens of competitors. According to Red Star, The Maniacs ended after Wendell Red Star Sr.’s death.

“Older Crows have told me, ‘White people had The Beatles, we had The Maniacs,” Red Star says. “To me, they’re legendary.”

And now, the subject of a photographic tribute befitting local legends.

Wendy Red Star Exhibitions

January 25 – March 17

Solo Exhibition

The Maniacs (We’re Not the Best, But We’re Better Than the Rest)

(timeline of her father’s life based on his music)

University Art Gallery, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces

Through February 18

Group Exhibition

Dress Matters: Clothing as Metaphor

Tucson Museum of Art, Tucson, Arizona

Through February 24

Curated Exhibition (Red Star’s work not displayed)

Our Side: Elisa Harkins, Tanya Lukin Linklater, Marianne Nicolson, and Tanis S’eiltin

(Native women’s voices in contemporary art)

Missoula Art Museum, Missoula, Montana

From the February/March 2018 issue.