Although his art career was tragically brief, Jerome Tiger’s work has left a masterful impression.

Jerome Richard Tiger lit up the art world like a shooting star for just five short years in the 1960s. During that time, the mostly self-taught Creek-Seminole artist from Muskogee, Oklahoma, sold his paintings as fast as he could finish them, won award after award, and sold out at his one-man shows, winning critical acclaim along the way. Early in his career at a group show at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he was asked to replace most of his stock twice. He fled his one-man show there in 1966 because patrons were fighting over his work.

His life was cut short in the early hours of August 13, 1967, when, after a night of shooting at fence posts with friends, a bullet discharged accidentally from his .22-caliber handgun, killing him instantly and ending his promising career. Even so, his legacy of distinctive nontraditional paintings, sketches, and sculptures would change the face of Native American art.

Tiger had drawn animals and humans on anything he could find for as long as anyone could remember and often found himself in trouble for defacing his schoolbooks. Once he even turned an old barn into his canvas for a mural. In April 1962, after having experimented with a variety of media and subjects, the 21-year-old met Nettie Wheeler, a local expert on Native American art more than 50 years his senior. She explained the rudiments of Native American art to him, suggested he try tempera, and became his friend and mentor. Within months, two of his paintings would win honorable mentions at the Philbrook Museum’s 17th annual Exhibition of American Indian Painting and Sculpture and third place at the Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial in Gallup, New Mexico.

The young artist set about his new venture with a passion, painting long into the night in a corner of the bedroom while his wife, Peggy, lay reading on the bed and his two young daughters slept in the next room. Working quickly on blue poster board, he painted with a single brushstroke, using tempera because he liked how quickly it dried. He never erased, and, being a perfectionist, he threw out pieces that didn’t meet his standards. It’s been said that better art could be found in Tiger’s trash than hangs in most galleries.

His elder daughter, Dana, says he could produce up to 10 or 20 paintings in a night when needed. Rance Hood, a contemporary of her father’s, once told her that her dad’s hand was a blur when he drew.

Working in his small, crowded home with his little children around could spell disaster. Dana admits she was often the culprit and laughingly recalls the time she got blue paint on a painting and her father had to turn the blob into a small blue dog; years later she found another piece in her Uncle Johnny Tiger’s attic that hadn’t been so easy to remedy — her dad had titled it Dana’s Masterpiece. “I felt bad about it, but I also thought it was sweet that he handled it so well,” she says.

Tiger lived his life as passionately as he painted. Although quiet and respectful in demeanor, he had a strong sense of self-confidence and possessed a streak of recklessness. Peggy Richmond saw it the day they met, when she rode her large Appaloosa stallion at a full gallop up to a group of boys. Most of them scattered, but Tiger stood there calmly and reached out for her reins. The connection was made — the pair became inseparable and married eight months later.

Born at the Indian hospital in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, on July 8, 1941, Tiger attended public schools in Eufaula and Muskogee, Oklahoma. After dropping out of high school at age 16, he falsified his age and joined the U.S. Navy, serving in the Naval Reserve from 1958 to 1960. He also worked as a manual laborer at Teel’s Laundry. He more than toyed with being a prize fighter, competing in the state Golden Gloves program and winning the Oklahoma middleweight crown in 1966. (Periodic injuries from boxing meant his paintings were sometimes delayed or finished with his left hand.)

But he was determined to be an artist. Deeply steeped in Muscogee culture by his grandparents, Tiger followed his grandfather’s advice to paint what was in the Creeks’ heart. Largely unexposed to traditional Native American art, he approached the subject with fresh eyes, breaking many of its rules. The autumn after meeting art expert Wheeler, he enrolled in Cooper Art School, part of a government relocation effort to assimilate American Indians into mainstream culture by separating them from other tribal members. In many ways, Tiger was an exemplary student: He attended classes, helped classmates with their projects, and was recommended for outside paying jobs such as textbook illustrations and calendars.

While still in art school, he would send home paintings to be sold by Wheeler, who was setting up shows for him. His first one-man show, at the Muskogee Public Library in December 1962, was a sellout; with the proceeds, Tiger bought his first new car. Things were going well, but in his second year of school, he overheard a comment by one of his instructors that could have derailed his career. Tiger’s wife recounted the incident in an article she wrote about her husband: “Sure, Tiger is good,” the teacher said, “but he is going to have to follow the rules. When we get through with him, he will be just another Indian who bit the dust.”

Tiger left art school but continued to paint his way to a legacy that would prove his detractor wrong indeed.

Just two weeks after the birth of his only son, the happily married 26-year-old father of three died, having painted prolifically for only five years yet having managed in that time to create a body of work that would become highly influential.

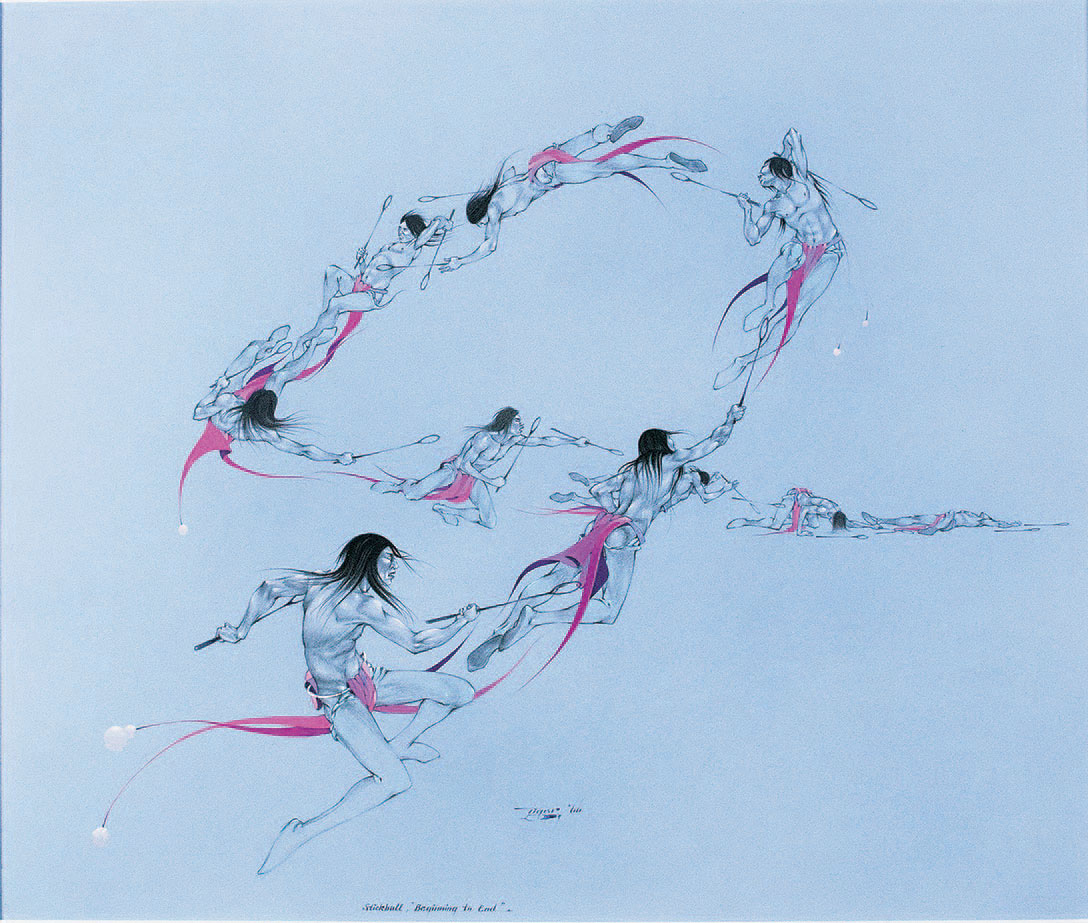

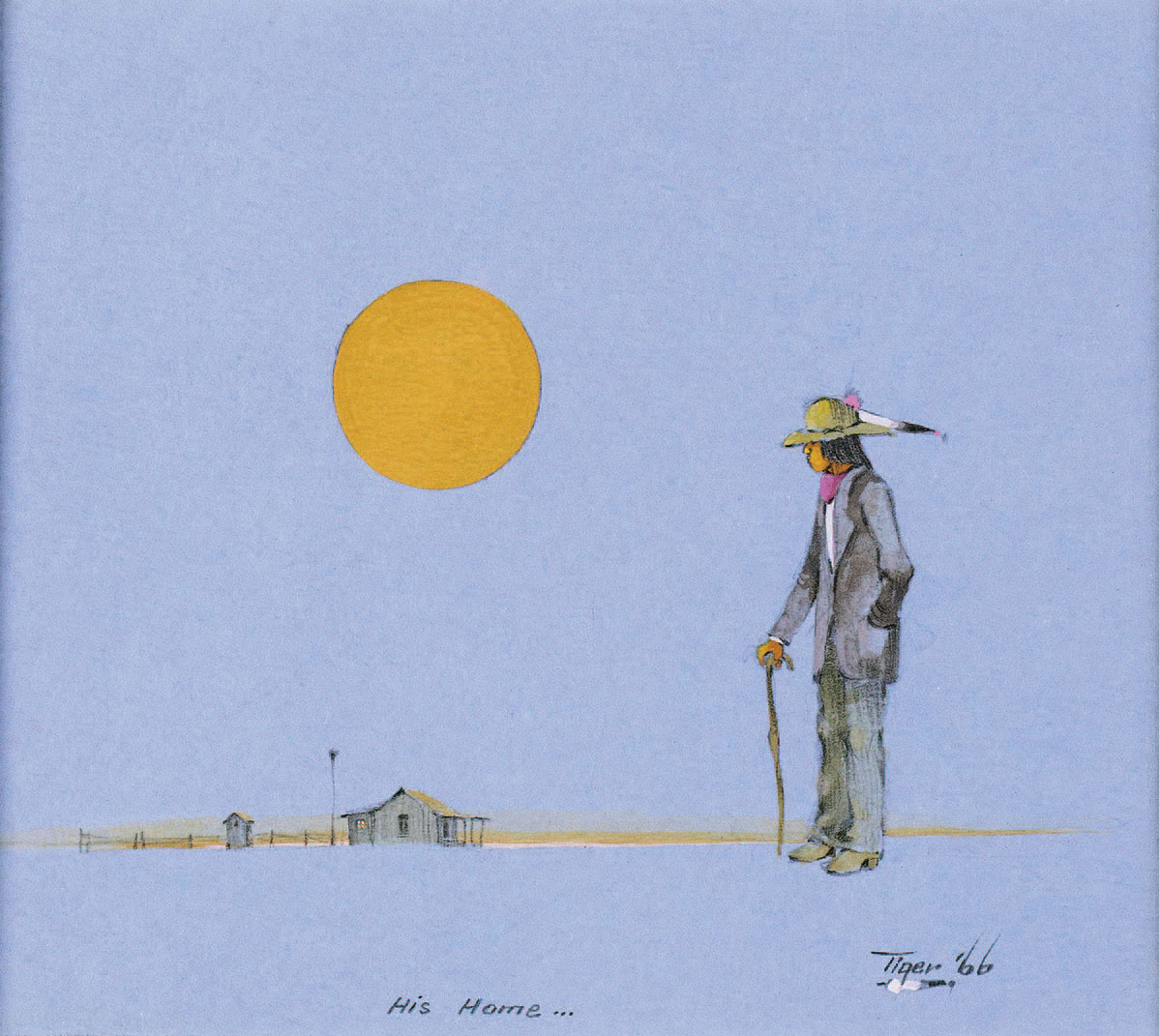

“He just painted what he saw every day, what he knew: his community, his family, his friends,” says Eric Singleton, curator of ethnology at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, which has mounted an exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of Tiger’s death. Singleton especially appreciates how Tiger’s work captures life and humor. “Two of my favorites are Stickball ‘Beginning to End’ and His Home. I have another [that] shows a little boy wearing his father’s hat and belt — both too large — getting ready for the stomp dance.”

As Lloyd Kiva New, cofounder of Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts, recalled in a 1978 interview, Tiger’s paintings “ran the gamut from a feminine sensibility to virile, almost macho, forcefulness. ... He was just a very fine artist, period. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci are people I have a tendency to compare his greatness to, more than to any Indian artist.”

Life and Legacy: The Art of Jerome Tiger is on view at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City through May 13, 2018. Visit nationalcowboymuseum.org.

From the January 2018 issue.