If you’re a fan of authentic early ledger art and have a big budget, but don’t know where to start, here are two names to remember and research: Joseph No Two Horns and Frank Henderson.

A little more than 100 years after he created it, young Arapaho artist Frank Henderson’s ledger art legacy scattered to the collector winds after the 1988 gallery show American Pictographic Images: Historical Works on Paper by the Plains Indians at the Alexander Gallery in New York. While the show was still hanging, The New York Times ran a lengthy story about it in May of that year.

The Times article explained that gallery owner Alexander Acevedo had acquired the rare 1882 volume Frank Henderson’s Drawing Book and leafed it out, mounting a selling exhibition of the framed individual pages, which carried 1988 price tags ranging from $1,500 for a simple sketch to $30,000 for a complex drawing. He preserved the entire ledger after a fashion in a 200-page catalog that duplicated the original ledger’s red marbleized cover and contents. The ledger included a stunning 87 drawings, which told the story of the Arapaho. Measuring about 11 inches by 5 inches, almost all of the elaborate pencil-and-ink images were by Henderson; a few were drawn by others.

His Indian name is unknown, but he was called Frank Henderson in 1879 when he was sent at age 17 from Darlington, Indian Territory (now western Oklahoma) to the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Orphaned as a child, he suffered homesickness and poor health during the year and a half he was at Carlisle. Returning to Darlington in 1881, he worked with missionaries and finished his book of drawings before his death at age 23 in 1885.

Henderson communicated the intent of his artistic effort in a note, dated December 12, 1882, on the first page of his book. “I have say to you this Monday afternoon I try hard to make you Indian picture,” he wrote to Martha K. Underwood, whom he had known at Carlisle and to whom he would mail his ledger full of drawings. “I wish you could write soon. Ah you pleased with it? I am your friend Henderson.” Underwood would bequeath the book of drawings to a grandniece; it would descend through the family and eventually be acquired by Acevedo.

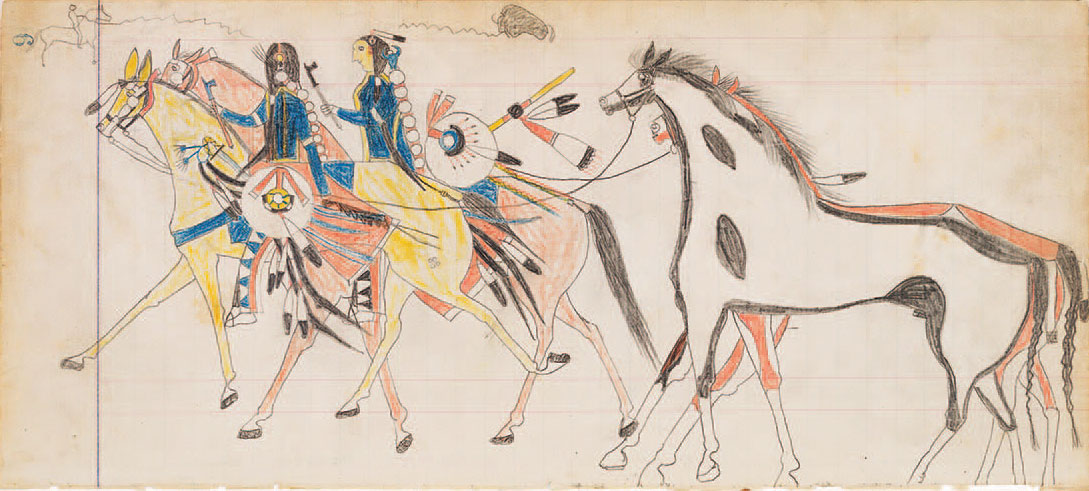

“Henderson’s finest drawings, which are as intricately detailed as Gothic tapestries, document Indians riding into battle wearing feathered war bonnets, carrying boldly patterned shields and spears. Others depict mystical myths, tribal councils, courting customs and scenes in the wild of such incidents as eagles attacking rattlesnakes, a mountain lion preying on a rabbit,” the old Times article reads, ultimately describing the fate of many ledger books of the early era: “All of the book’s extraordinary pictures — horses painted yellow and blue, Indians in pink regalia, wildly colorful battle scenes and pictures showing women tending fires while the men watch, wrapped in boldly patterned red-and-black blankets — were removed from the ledger and framed. Each page — a few have drawings on both sides — is to be sold separately.”

A little more than 25 years later, back on the Plains where ledger art was especially prevalent, Antiques Roadshow made its way to Bismarck, North Dakota, in May 2014. Expert tribal arts appraiser and collection formation and development specialist Ted Trotta was especially excited to see the State Historical Society of North Dakota’s substantial collection of works by Joseph No Two Horns. A segment of the show was devoted to the valuable and highly collectible ledger art of the Hunkpapa ledger artist.

Displaying one of the artist’s works, Trotta broad-brushed his life: “We believe Joseph No Two Horns was born around 1852. He lived a long life; he passed away in 1942. He was 14 years old on his first war party. By the time of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, he was a mature warrior, and Joseph No Two Horns went on to become a working artist recollecting that great moment in their tribal history.”

No Two Horns’ “muse,” Trotta explained, was his days as a youthful warrior, a theme he would recall and portray with ethnographic accuracy over and over again in his work. Of the dozens of colorful drawings in the historical society’s collection, Trotta chose a particularly poignant battle scene to show and discuss. As with most ledger art, the drawing is autobiographical.

“This is the epic moment in Joseph No Two Horns’ life,” Trotta said. “He’s at the battle, his horse is wounded, his favorite horse, a [blue] roan. The horse falls; he falls with it. He’s carrying a horse quirt with a sawtooth design. This signifies that he’s a member of the Kit Fox Society, a warrior society, a great honor. [It’s] also a tremendous responsibility: If he falls, or if his comrade falls in battle, he takes his lance and pounds it into the ground and there’s no retreat; he fights to the death to protect himself or his comrade.”

The shield in the drawing is one No Two Horns actually created. The flower on the paper, on the other hand, has nothing to do with the artist and everything to do with the fact that ledger art was created on whatever paper was available. “In the early days, in the 1860s, 1870s, a cavalry officer might have provided No Two Horns or another Plains artist with ... a lined ledger book.”

A good ledger drawing, Trotta pointed out — one that is “aesthetically pleasing, that perhaps depicts some accouterments, in good condition” — might fetch $2,500, $3,500 (in 2014 dollars), while “an exceptional example could be worth quite a bit more.” In the case of Joseph No Two Horns’ work, Trotta said, a drawing like this battle scene — “the fact that we know who depicted this great work” — would sell for $15,000 to $20,000 in a retail setting. By 2015, that figure had been revised to $17,500 to $23,500 at auction.

Read The New York Times article “ANTIQUES; Bold Images Capture the World of the Plains Indians” at nytimes.com, or search out the catalog, American Pictographic Images: Historical Works on Paper by the Plains Indians (text by Karen Daniels Peter-sen, 1988). Watch the Antiques Roadshow Bismarck segment at pbs.org. Find Ted Trotta at trottabono.com.

From the August/September 2017 issue.