A ledger drawing done by Lakota warrior Crow Dog while imprisoned in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, is a case study in the many aspects of early ledger art that experts and collectors must consider.

It might be an expression of boredom, a Lakota prisoner’s drawing in a notebook while sitting in jail in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, awaiting the trial that finally arrived in March 1882. But it is also authentic ledger art, and an example of why museums and Western art collectors covet pieces by warrior artists who lived the last days of the American frontier and drew their accomplishments on paper.

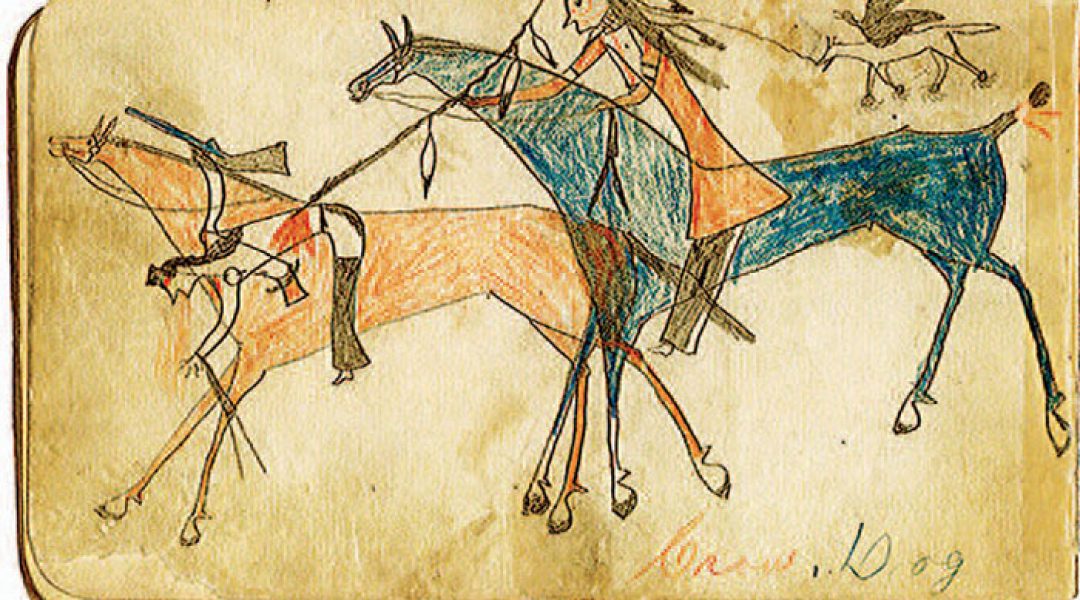

“That’s the most collectible of anything ... very expensive,” says Western art dealer James Aplan of James O. Aplan Antiques & Art in Piedmont, South Dakota. A good example, Aplan says, is that picture the warrior Crow Dog drew in that Deadwood jail. There is Crow Dog, riding right to left across the picture to drive his lance into a fleeing warrior who carries a carbine. Crow Dog is easily recognized because of the glyph or sign that identifies him — a crow on top of a dog, trailing somewhat behind and above the rider as though tethered by a string.

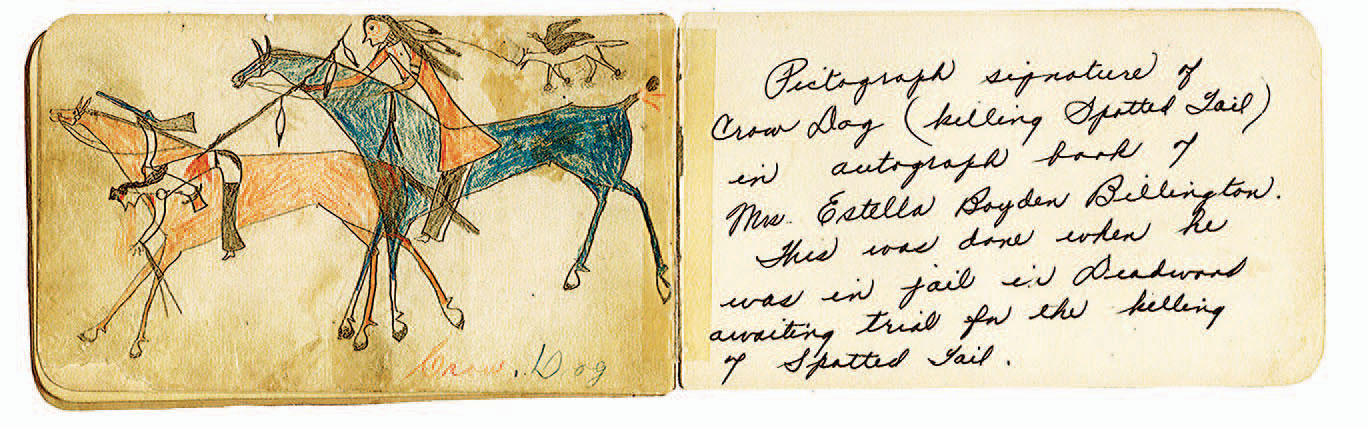

Crow Dog, a Brulé Lakota, was facing trial for killing another Brulé, Spotted Tail, at the time he drew the picture. He was eventually convicted, sentenced to be hanged, and then released on appeal in a landmark case about jurisdiction and tribal sovereignty. In the past, some mistakenly viewed his Deadwood drawing as depicting the fight with Spotted Tail. Darrel Nelson, exhibits director for Deadwood History, says that’s not the case. It’s just an incident that came out on paper when a girl named Estella, the daughter of Demetrius Billington, the jailer, loaned the prisoner a notebook.

“My understanding is that the jailer’s daughter, this Billington, let Crow Dog draw in her little album,” Nelson says. “I also understand, unlike what was previously thought, the drawing does not refer to him killing Spotted Tail. It’s another incident. But it’s clearly Crow Dog. There’s him and here’s his little image floating behind him. It’s some other situation, but it’s absolutely his work.”

The Crow Dog piece is in the Deadwood Days of ’76 Museum now because Estella, the jailer’s daughter, donated the notebook to help preserve a crucial part of Deadwood history. Other pieces by Plains warriors found their way into collections nearly nationwide — including some from as early as the 1860s, when whites first recovered ledger books depicting warrior exploits from southern Plains battlefields.

When John R. Lovett Jr. and Donald L. DeWitt compiled their 1998 Guide to Native American Ledger Drawings and Pictographs in United States Museums, Libraries, and Archives there were examples of pictographic or ledger art in archives in 22 states west of the Mississippi and in 19 eastern states. That’s surprisingly wide distribution, given that scholars consider only the Plains Indians to have produced ledger art in that period.

The Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives has the largest number of ledger drawings with approximately 2,000 pieces. When Lovett and DeWitt did their guide, some of the other sites unusually rich in ledger art included the National Museum of the American Indian in New York, with 634 drawings; the Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with 457; the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, with 218; and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, with 204.

Scholars disagree about when that first flowering of ledger art ended. Lovett and DeWitt, when compiling their guide, used 1940 as a cutoff date, reasoning that art created after that would likely have been produced by artists too young to have experienced pre-reservation life.

Along with the name glyph that is often found on ledger art from frontier days, there are a few other markers collectors can look for on pre-1940 ledger art. “A majority of ledger drawings share common characteristics, such as a lack of perspective, and action scenes that usually move from right to left,” DeWitt and Lovett write. “Ledger drawings are also egocentric in that the warrior-artist is nearly always the focus of the drawing’s action.” However, there’s a wide range in artists’ style, content, and quality, the two explain.

Because contemporary artists often use authentic ledgers from the late 1800s, collectors shopping for 19th-century ledger art will have to do their homework. Still, ledger art from the early period is out there for the collector who knows what to look for.

From the August/September 2017 issue.