Although it took painter George Paliotto a while to realize, art and the West are ingrained in him.

The twin passions of art and the West can’t help but come out in George Paliotto’s family. The California-based painter began his career in teaching, counseling, and pharmaceutical/medical sales, but then he switched gears and attended life-drawing and painting classes at a local atelier. There he spent many long hours honing his craft, eventually rediscovering Western and Native American themes as a favorite subject for his artwork. Soon he would find himself making it to the Saturday night stage at The Russell Live Auction.

It might seem a surprising trajectory for a guy born and raised in Cleveland — or not. Paliotto remembers exploring his attic as a kid and coming across a sketchbook of life drawings his father had done. “My dad, who owned a construction company, painted Native Americans, of all things, in the off-seasons,” Paliotto says. Growing up, the younger Paliotto loved westerns — Roy Rogers, The Lone Ranger, Gunsmoke, The Rifleman — and his dad got him a horse when he was about 10. They boarded the horse in the country, and George’s dad regularly took him to take lessons and to ride.

As George was getting into riding and showing in Western pleasure, his artistic talent was beginning to manifest. He received early encouragement from a high school art teacher who taught him oil painting. In art class he would meet his future wife, but charting their future, he headed not for art but for Bible college and seminary. After working in counseling and teaching, he put in the better part of his career in pharmaceutical sales.

He came to an artistic crossroads during a trip to Idaho.

“Things had worked out so I could go back to school and do something different,” Paliotto says. “I asked myself, Do I want to stay in this field? Around this time, my wife and I went for a week to Coeur d’Alene [Idaho] to visit my son Kyle, who is an accomplished artist. He had a studio space in a building in the back of his yard. I’d go out to the studio with him every morning while he painted. I bugged him enough the first day making suggestions that the next day he had an easel set up for me. That was the spark that reawakened my interest in art.”

C&I talked with Paliotto about how his love of art and the West merged for a second act.

Cowboys & Indians: What happened after you realized you wanted to reinvent yourself as an artist?

George Paliotto: I came back to Thousand Oaks [California] and thought maybe I’d start a gallery. And then I thought I’d take a workshop in art. I was very fortunate to live about 10 minutes away from the California Art Institute, where I studied with Glen Orbik, Jeremy Lipking, Tony Pro, and several other really good teachers. Most of the classes I took were drawing from life and painting from live models. I logged many, many hours studying and drawing from life.

C&I: How did Western themes become your focus?

Paliotto: I started out doing figurative and portrait work and had gotten into some national shows and a couple of galleries. Then I got interested in riding again. The guy I was leasing my horse from did reined cow horse stuff, and he taught me how to work cattle. I was having so much fun doing reining patterns, etc., that I bought a horse and got into competing and working with different trainers. Rob Frost, the president of the Ventura County Cattlemen’s Association in Santa Paula [California], invited me on a branding, where I was able to take several reference photos of the guys and gals doing ranch work. I started taking photos for later art pieces at these kinds of things, and people liked the work. It allowed me to bring people, horses, painting, and drawing all together.

C&I: Did anything in particular solidify your interest in portraying Western and Native life?

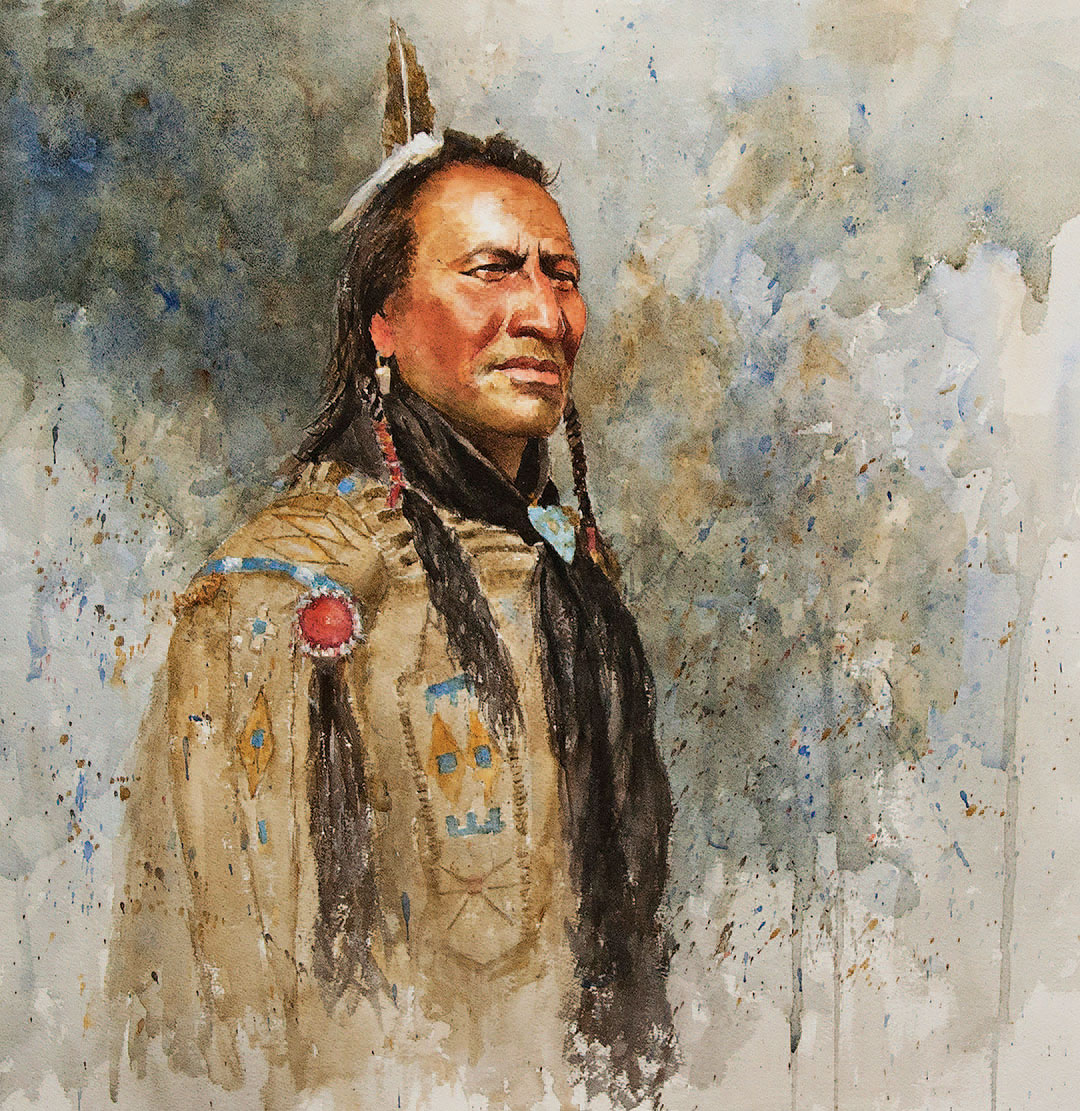

Paliotto: Shearers’ Artist Ride in South Dakota was another turning point. That was really my introduction to American Indians. I had thought about American Indian themes, but that’s where I actually met Native Americans and became friends with them. After spending three or four days together — all day, working, eating, and drinking together — you get to know each other pretty well. That’s where I met Zola Greene and learned more about the Native American culture. It was last summer, in August. Her father was Chief David Bald Eagle. He had just passed away a few weeks before.

C&I: And that led to one of your best pieces of work, “Dream Catchers.”

Paliotto: At the Artist Ride photo shoot, people bring many different props, and you come up with ideas on the spot sometimes, looking at what you have. Zola had an American flag and a horse. She came up with a pose with the horse, a rifle, and an American flag. A few weeks later, after returning to my studio and looking through the material from South Dakota, I came across the shots of Zola and the horse. I knew immediately that there was something more to this scene, and a concept emerged as I thought about what I had learned.

Then I started research on her father. He was a World War II hero, an actor in Hollywood, a stuntman, and trained horses for the military. The guy was a phenomenal person. The fact that he was a veteran really struck me. Of all the minorities, American Indians have the largest percentage in the service. I had this idea to incorporate Zola’s pose and superimpose her father on top of it — a head painting of him as a spirit. She’s in full color. He’s in shades of blue; his spirit is looking down on her. It combines the ideas of Native American women who fought and worked alongside the men with Native Americans in the U.S. military and the love of a father and daughter. That painting came to be called Dream Catchers. She was so moved by the piece that she contacted me and wanted it for herself.

C&I: That must have been gratifying.

Paliotto: Meeting Native Americans like Zola, and getting to know more about them, has given me an even deeper level of respect for them. I really try to honor their culture and them as a people. That’s true for whomever I paint or draw. I have a high regard for the American Indians’ and the cowboys’ culture and lifestyle. There’s a real beauty and uniqueness in those cultures.

C&I: How important is it to you to represent them accurately?

Paliotto: I try to paint the “Spirit of the West” portrayed through the personalities of the men and women who make it what it is — the beauty and drama of the heritage and lifestyle both past and present. I’m not just rendering a photorealistic painting. We have cameras for that. But I’m looking for how this subject makes me feel or what it makes me think about and then try to convey this on canvas.

It’s important to me to accurately capture the person and also the way of life, to try to preserve the history and heritage of working ranchers, cowboys, Native Americans. At the same time I want it to be a creative, expressive work of art. A guy who bought one of my paintings at The Russell said he really liked it because he grew up in such and such place and that’s exactly what it was like. The ranchers see authenticity and comment, and it makes me feel good. You want to paint what you know. I ride horses and work cattle — I have a connection that helps me be authentic in the way I portray it.

Visit the artist’s work at georgepaliotto.com.

From the August/September 2017 issue.