For a 30-year inside view of contemporary Plains Indian communities, check out the Ken Blackbird Collection.

Cowboys & Indians: What exactly does the exhibition Textured Portraits consist of?

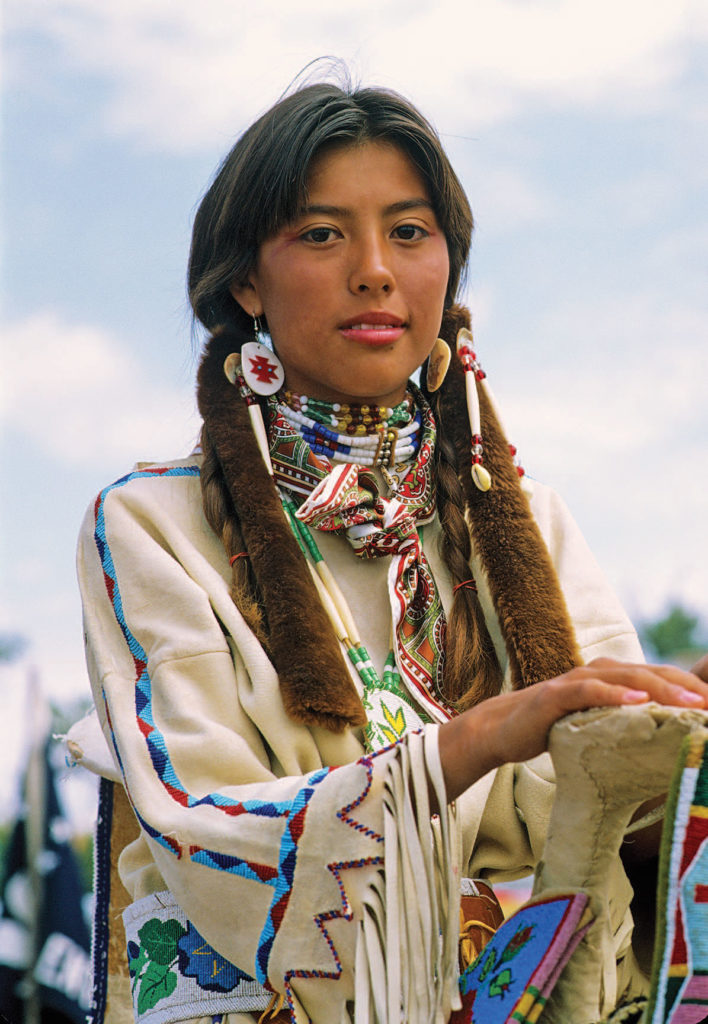

Emma Hansen (Pawnee), curator emerita and senior scholar, Plains Indian Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West: The focus of the exhibition is the Native people of the Great Plains as shown through over 30 years of photography by Ken Blackbird, who is himself an Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribal member.

Natalie Panther, PhD, program officer, Helmerich Center for American Research, Gilcrease Museum: There are 33 framed prints (7 verticals, 23 horizontals, 3 panoramas). Ken Blackbird has been a documentary photographer of Native American life for 30 years, and this exhibition will feature a sampling of his total collection. Most of the prints are 21.5 by 26.5, and they are ink-jet prints. These beautiful and touching images of contemporary Native American life — including powwows and ceremonies — show Blackbird’s vision of the American West as he’s lived it.

C&I: How did the exhibition come to be?

Panther: I first learned about this photography exhibition from Emma Hansen, curator emeritus from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West and guest curator for the Gilcrease’s exhibition Plains Indian Art: Created in Community, February 26, 2017 – August 27, 2017. This exhibition highlights some of the most talented artists among Plains Indian communities throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Emma felt very strongly that we needed a contemporary Plains artist to round out the exhibition, and Ken’s photographs were a perfect fit.

Hansen: I first met Ken when I came to Cody, Wyoming, to assume the position as curator of the Plains Indian Museum in the early 1990s. In 2000, the museum undertook a complete reinterpretation with several goals in mind. One goal related to addressing through our exhibitions the contemporary lives of Plains Native people. I contacted Ken about possible photographs for the exhibition and he was very generous. Many of the photographs and large photomurals throughout the museum's galleries are works Ken completed in photographing on several Northern Plains reservations and carry, perhaps, subtle messages. For example, facing a gallery about the traditional roles of men as Plains Indian hunters and warriors, there is a photomural of a contemporary Northern Cheyenne veteran in uniform carrying the American flag as a member of a powwow color guard.

C&I: That would be one of the “textured portraits.” What is meant by that title?

Hansen: I think there are likely several meanings of this title to Ken, who actually created the title. To me, the title refers to the multiple aspects or layers of meaning one can experience in viewing Ken Blackbird’s photographic work. In many cases the photographs stand alone as striking portraits of individuals — especially elders — whose faces reflect their life experiences; or beautiful and distinctive landscapes and scenes of buffalo in the Northern Plains. However, the images of Plains Native people — whether dancing at powwows, rounding up tribal buffalo herds, or just riding horses or swimming in the river — exhibit the continuing vibrancy of the cultures. Images of powwows that are often multigenerational speak to the significance of community life and the continuance of traditions from the old to the young.

C&I: What makes Blackbird’s photographs distinctive?

Hansen: Ken’s artistry and talent for composition, lighting, and other techniques are obvious. However, one factor that distinguishes his work from other photographers who work with Native American subjects is that Ken understands the significance of cultural traditions he may be photographing and has taken the time to learn and show respect for the cultural protocols that guide the work of a photographer in a reservation setting. Because he is known and respected for his work, he may be welcomed into events or situations where other photographers have little access.

Panther: I personally appreciate his photographs because they offer a more contextualized and nuanced view of Native American peoples and culture. I think there are a lot of misconceptions out there about contemporary Native American life, and my hope is that visitors who come to see this photography exhibition will gain a deeper appreciation and understanding of life in Indian country.

C&I: Do you have some favorite shots?

Hansen: I admire many of the photographs in the exhibition. But I particularly enjoy the images of the children with horses at Crow Fair. There are two in the exhibition of the children watering their horses on the Little Bighorn River with other children swimming in the background. In my times at Crow Fair, I remember that seeing how naturally and skillfully the children ride their horses through the camps and down to the river is one of the many pleasurable aspects of this event. I also admire the photograph of Juanita Tucker, the elder, whose face shows her wisdom and life's experiences.

C&I: How about that striking Crow Fair tepees-with-rainbow image?

Hansen: One of the characteristics that attract visitors to Crow Fair are the hundreds of tepees throughout the campground belonging to families of Crow tribal members as well as people from other Native cultures. The rainbow image is just a beautiful photograph of that setting underneath the Montana sky. The photograph Headdresses, Fort Belknap is one of Ken’s many photographs of powwows that he has taken over the years. Sometimes he highlights details of regalia such as feather bustles, shawls of women fancy dancers, or roaches, feathers, and headdresses. This particular photograph emphasizes the dramatic action and excitement created by many male dancers during the evening at the Fort Belknap powwow.

C&I: What do you hope the exhibition will achieve?

Hansen: I think the exhibition creates an overall positive feeling about the enduring traditions of Plains Indian people that are passed from generation to generation. The exhibition relates to the continuing relevance of such traditions for people today. Hopefully, visitors will appreciate the artistry of Ken Blackbird’s photography. Perhaps they will also learn more about Plains Native cultures, arts, traditions, and contemporary lives and understand that Indian people are still vital members of their own communities throughout the Plains and beyond.

Textured Portraits: The Ken Blackbird Collection is on view February 26, 2017 – August 27, 2017, at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in conjunction with an exhibition on Plains Native art titled Plains Indian Art: Created in Community. For more on the originating museum, visit the Buffalo Bill Center of the West online. Textured Portraits: The Ken Blackbird Collection was created in 2014 as a traveling exhibit, with a grant from the Western States Arts Federation and the NEA, among others. All photographs in the exhibit are from MS 426, the Ken Blackbird Collection, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, USA. Gift of Ken Blackbird.