The acclaimed photographer’s images stand the test of time.

Few images of Native American life command respect or stand the test of time like the collection of portraits captured by photographer Frank A. Rinehart at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. Spread across 184 acres in Omaha, Nebraska, the exposition was meant to showcase the developing West, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. A highlight of the larger event was the Indian Congress, a gathering of some 35 tribes represented by more than 500 delegates — at the time, the largest such event the world had ever seen. The purpose, according to organizers, was “to make an extensive exhibit illustrative of the life, native industries, and ethnic traits of as many of the aboriginal American tribes as possible.” Attendees would “camp in tepees, wigwams, hogans, etc., on the exposition grounds and ... conduct their domestic affairs as they do at home.”

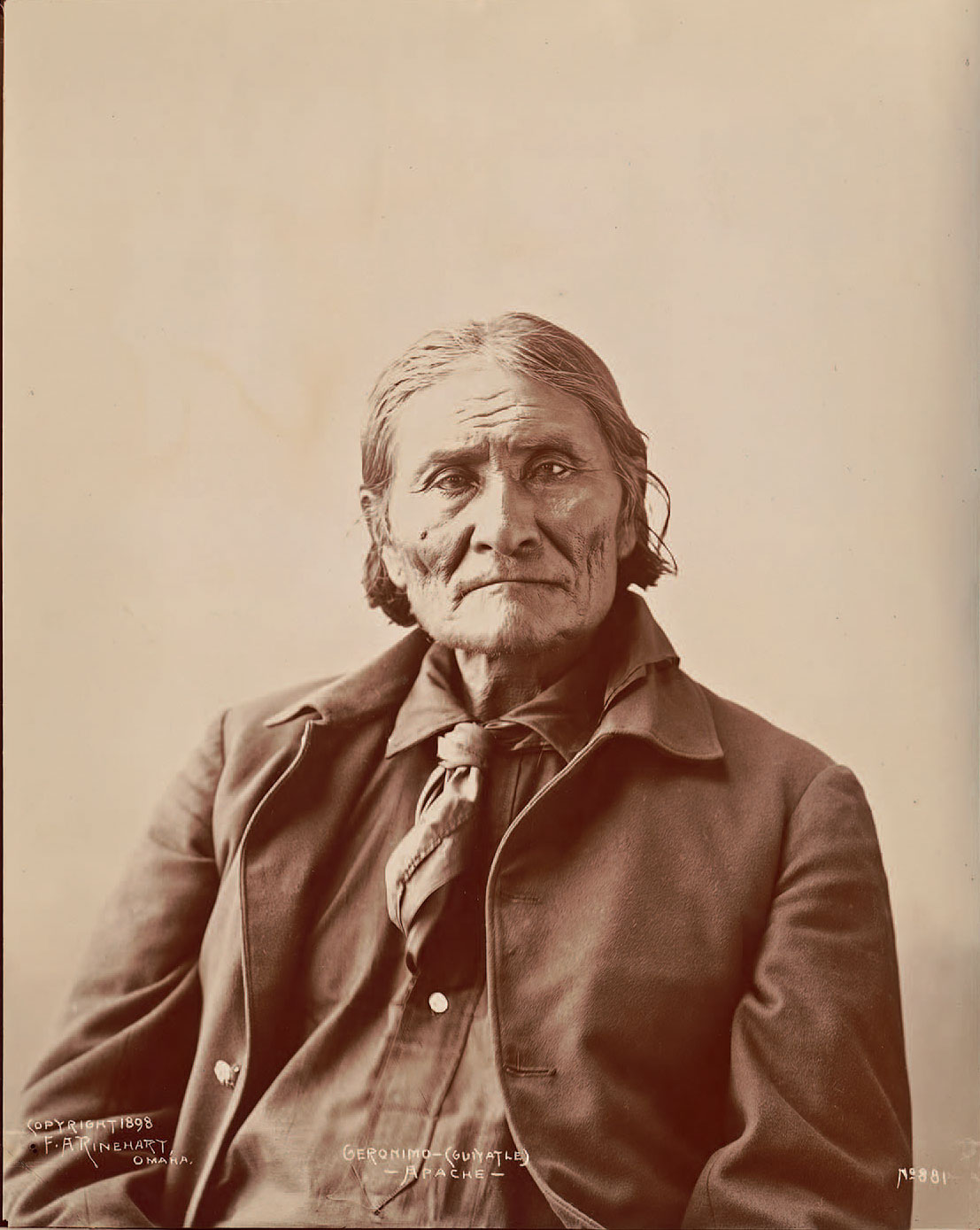

“At this time, Native Americans were viewed as a people of a vanishing way of life,” according to the Museum of Nebraska Art. “They were seen as noble and not as an enemy to be feared.” Into this milieu walked 36-year-old Illinois-born photographer Frank A. Rinehart. A one-time apprentice of famed Western landscape photographer William Henry Jackson, Rinehart was by then already a skilled artist and technician. Granted exclusive rights to photograph the Indian Congress, and using an 8-by-10 glass-negative camera, Rinehart and his assistant, Adolph Muhr, set up a studio on the grounds. They proceeded to capture some of the most striking images of Native Americans, many in ceremonial dress, ever conceived.

Whereas many previous photographs of Native Americans had a dull ethnographic or sometimes “savage” quality, the Rinehart photos presented their subjects with dignity and resonance. Along with work from other contemporary photographers, they helped cast the very idea of Native Americans in a more profound light in the minds of many Americans. The images also captured a frantically shifting world, not just for Native Americans, but all Americans.

“It isn’t that the photographs depict the end of a way of life, as much as a way of life that was changing rapidly,” says Simon Ortiz (Acoma Pueblo), a professor of English and indigenous literature at Arizona State University, a key figure in the Native American Renaissance of the late 1960s, and author of the 2005 book Beyond the Reach of Time and Change: Native American Reflections on the Frank A. Rinehart Photograph Collection. “The photographs were taken at a time when the United States was really first asserting itself as an international power,” he says. “[Domestically] we were almost 10 years from the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre that marked the end of major armed resistance by indigenous people in the Plains. This was very prominent in the Native peoples’ minds, and they knew there was not a lot they could do.”

Among Ortiz’s favorite images is the portrait of a stoic Geronimo. In one of the strangest episodes from the Indian Congress, the legendary Apache chief was allowed to attend the event, despite at the time being in federal custody as a prisoner of war at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. He spent his time at the Congress under constant guard by U.S. soldiers. “He looks more or less sad,” Ortiz says. “But I also see in the photograph a sense of romanticism.”

So why did these people — Assiniboine, Apache, Crow, Flathead, Iowa, Ponca, Sauk, Sioux, Wichita, and many others — consent to being photographed? Many likely didn’t, says Ortiz, due to traditional beliefs against depicting the spirit on paper or in material form. For those who agreed, however, Ortiz sees something that suggests a form of survival — a kind of coping mechanism in response to Euro-American colonialism.

“I would put it this way: They were in an era of much uncertainty; you didn’t know what was going to happen next,” he says. “Over time, especially if there’s no way you’re going to stop what is happening, you come to some kind of agreement with yourself, maybe a compromise to continue on, even against your original principles.”

As for Rinehart, sales of the images catapulted him into wealth and national prominence. In 1899 and 1900, he traveled with Muhr to numerous reservations, taking more than 1,200 portraits of Native Americans and building a reputation as one of America’s great chroniclers of indigenous cultures.

But how much of the groundbreaking work from the Indian Congress of 1898 was actually his? As the owner of the studio commissioned to document the exposition, Rinehart copyrighted the images and profited grandly from their sales. But most historians agree that it was Muhr who did most of the work with the subjects and took the actual pictures. The way of life the duo were documenting may have been changing, but human nature wasn’t: According to the Museum of Nebraska Art, “Argument over picture copyrights eventually led to Muhr leaving Rinehart’s employ.”

View the Omaha Public Library’s 3,000 original images from the 1898 exposition. Boston Public Library has more than 100 original images in its Frank A. Rinehart collection.

From the February/March 2017 issue.