Pioneering photojournalist Charles Fletcher Lummis tramped across the country, fought for Native American rights in the Southwest, advised President Theodore Roosevelt, and helped shape the development of Los Angeles — often dressed in buckskin and sombrero.

In the spring of 1888, when Charles Fletcher Lummis was scratching out a living as a freelance photojournalist in New Mexico, he wasn’t about to let a death threat keep him away from a scoop. The quirky 28-year-old Harvard dropout had gained national fame four years earlier when he had walked from Ohio to California to take a job at the fledgling Los Angeles Times, writing a witty regular newspaper column about his escapades along the way. But his fortunes had fallen since then. After nearly three years working at a breakneck pace as city editor in a boomtown, Lummis had suffered a stroke that had left him partially paralyzed, and he had retreated to the hinterlands of New Mexico to recuperate.

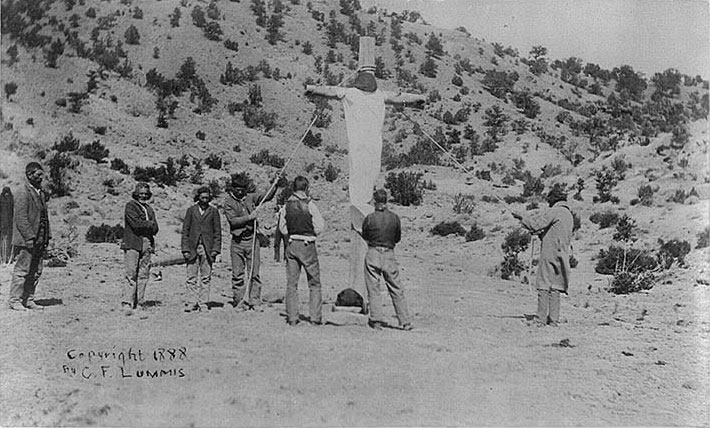

He was living in the hamlet of San Mateo, making ends meet by selling articles and photographs to publications nationwide about Pueblo dances, Navajo blankets and jewelry, Mexican American shepherds and their music, and other topics of interest in that exotic corner of the country. The most thrilling yet came his way in early March 1888 when he heard an eerie whistling sound wafting “like the wail of a tortured soul” out of a canyon near town. Asking around about it, Lummis learned it was a musical instrument used by members of a secretive Catholic cult called the Penitentes and that they were preparing to crucify one of their members on Good Friday.

“No photographer had ever caught the Penitentes with his sun-lasso, and I was assured of death in various unattractive forms at the first hint of an attempt,” he later recounted. The risk only added to the allure for Lummis. Just 5-foot-6-inches tall, he was muscular and pugnacious, and, as his readers had come to know during his “tramp across the continent,” he reveled in daunting challenges.

Determined to overcome the Penitentes’ resistance, Lummis met some of the group’s leaders, “overwhelmed them with cigars and other attentions,” and persuaded them to let him witness and photograph their Easter week rituals. The Penitente who had the honor of undergoing the crucifixion was tightly tied, not nailed, to the cross for several hours. But as Lummis told it, it was a scene that “might grace a niche in Dante’s ghastly gallery.” He sold stories about his daring run with the Penitentes, accompanied by his photographs, to newspapers from the Boston Transcript to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat to the Los Angeles Times, and eventually to one of the nation’s leading monthly magazines, The Cosmopolitan.

Later that year, on several occasions when Lummis was riding his horse on the range near San Mateo, he heard bullets whistle past. Some of the Penitentes had grumbled about his lurid depiction of their traditions, but he was sure they weren’t the ones out to get him. The common folk in San Mateo liked Lummis, a gregarious oddball who was learning Spanish quickly and hadn’t let his partial paralysis stop him from riding, roping, shooting rabbits, and rolling cigarettes with one hand. Besides, others around San Mateo had a more urgent interest in seeing him dead.

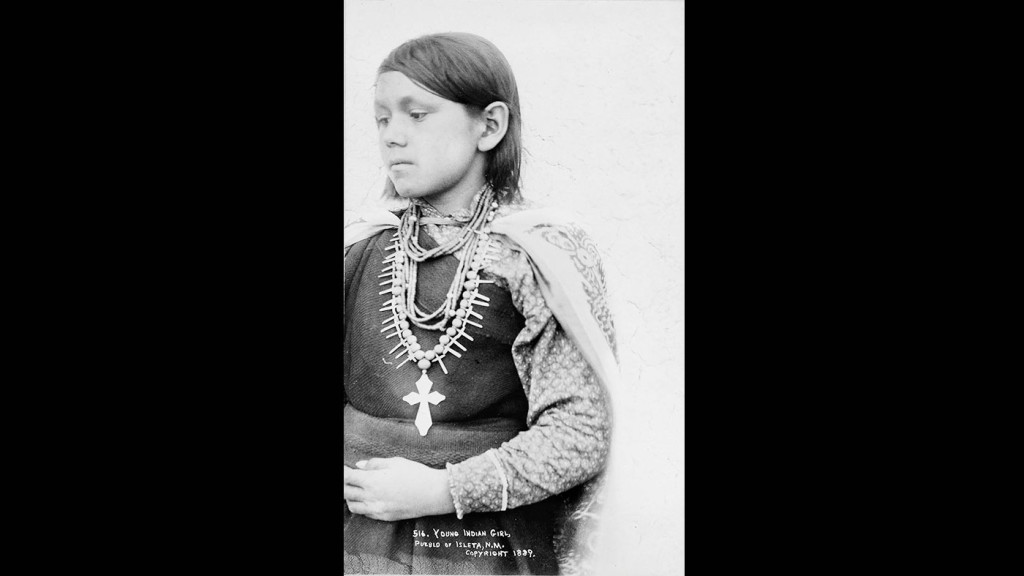

Lummis had turned his investigative energies in the latter half of 1888 toward a recent string of murders of nosy newcomers to that part of New Mexico, including a newspaper publisher and an election observer. He had built a case pinning blame for the killings on one of the most politically powerful clans in the county, then facing an unprecedented electoral challenge for a family-controlled seat in the territorial legislature. The Times ran Lummis’ story about the family’s long “reign of terror” on December 5, headlined “The Story of a Crime Thrillingly Told.” That report would surely raise the price that was already on his head, so the day after the story ran, Lummis left San Mateo and moved to Isleta, a Pueblo Indian village on the Rio Grande river south of Albuquerque, more than 100 miles away.

Apparently, that wasn’t far enough. Shortly after midnight on Valentine’s Day 1889, when Lummis took a break from writing and stepped outside his adobe dwelling to admire the moon, a would-be assassin hit him with a shotgun blast. Papers nationwide carried the news. Several reported that the plucky reporter had died. But the half dozen pellets that hit him narrowly missed his vital organs, and Lummis was back on his feet within days — “now loaded for bear,” as one paper put it — his career boosted and his legend enhanced.

Lummis would go on to write more than 20 books on the history of the Southwest and the cultural traditions of its people. He moved back to Los Angeles in 1892 and edited an influential regional magazine, initially called Land of Sunshine and later renamed Out West. He published the work of many leading and up-and-coming Western writers, poets, artists, and photographers of his era. On the side, he launched and propelled an eclectic array of civic and artistic endeavors to, among other things, restore Spanish missions, preserve Spanish folk music of the Southwest, and build a museum in Los Angeles for Southwestern Native artifacts. In the cause that became his most pressing lifelong passion, he relentlessly pressed, with some success, for improved treatment of Native Americans.

His social life was grist for gossip columnists for decades. His writer, artist, and musician friends mixed with socialites, scholars, and assorted luminaries at boisterous parties that Lummis called “noises,” at the home he built himself out of river stone in the bohemian Arroyo Seco neighborhood of Los Angeles. “No one invited ever failed to come,” the singer Edith Pla reminisced years later. As one of Lummis’ many devoted friends, Stanford University president David Starr Jordan, put it, he was “a human geyser of the first water, bubbling with enthusiasm.”

Lummis had an outsize ego and was iconoclastic to a fault, which grated on some of his contemporaries, his wives — there were three, in all — and children. But he was beloved by those who were not put off by his many eccentricities, one of the most conspicuous of which was a lifelong affinity for outlandish outfits. That predilection was first on display during the tramp. He set out from Ohio in red knee socks that drew guffaws from those who saw him off. He strode into Los Angeles, five months and 3,507 miles later, sporting Apache buckskin leggings and a coyote skin draped around his neck, an outfit that, as the Times described it, was “calculated to excite the curiosity of the police.”

A tourist from Chillicothe, Ohio, who dropped in on him in San Mateo and wrote an “amusing account of his bohemian ways” offered the first glimpse of a style of dress that would be one of his favorites for the rest of his life. Decked out like a Spanish don, under the influence of the aristocratic old New Mexican family that was putting him up, he “dresses in a suit of purple velveteen or corduroy and wears a big sombrero,” the reporter noted.

Lummis’ two-year sojourn in Isleta would leave an even greater mark on his life. He fell in love with the pretty young teacher at the Catholic day school in the pueblo, Eve Douglas, and married her after dumping his first wife, Dolly, whom he had left behind in Los Angeles. His marriage to Eve, which brought four children, would end in a fiery divorce 20 years later — amid a flurry of stories about his incessant womanizing — after she cracked the code he used in his diary to survey his extramarital conquests.

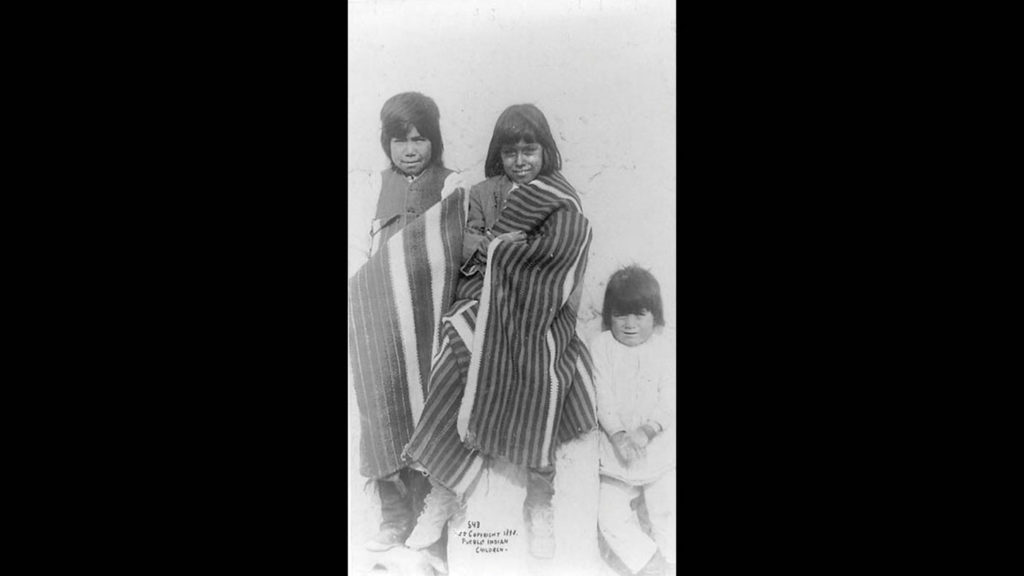

His experience in Isleta also turned Lummis into a fierce lifelong critic of the nation’s Indian policy. Soon after moving in, he learned that 36 children from the pueblo were held against their will in a government boarding school in which their parents had willingly enrolled them, only to be cut off from most contact with their families for years to come. That was a common practice, founded on the notion that Indian villages were pits of depravity and backwardness, and that parental bonds didn’t really exist since children were treated as tribal property.

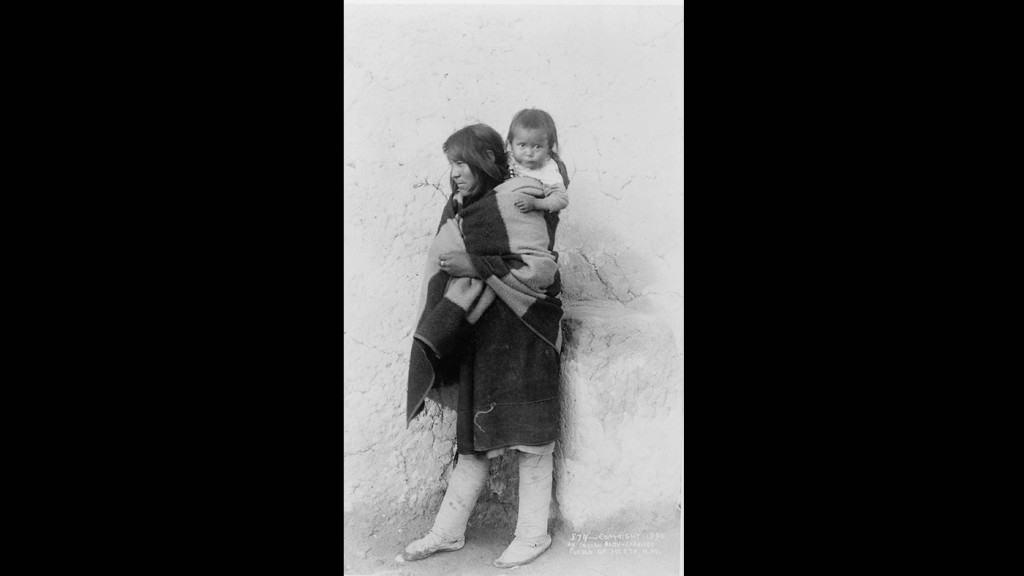

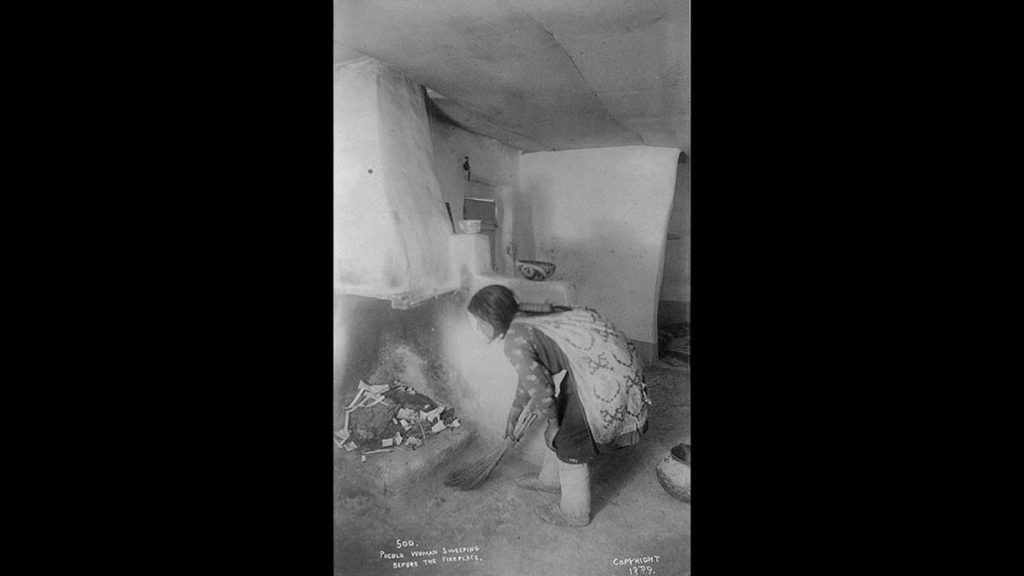

Lummis helped mount a legal case that succeeded in freeing the Isleta children from the boarding school. He also set about systematically dismantling the sordid view of Indian life promulgated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs through the stories he was writing for newspapers and magazines nationwide from an idyllically portrayed Isleta. Parents were “fairly ideal in their relations to their children,” he wrote in one article. In the two years that he lived among children of the pueblo, he wrote in another, he “never saw a fight or a quarrel or a sulk.” His photographs of children interacting with their parents and grandparents helped prove the point.

Photography was a passion of Lummis’ from the moment he acquired his first camera in 1886. He set off with it on a reporting trip through Arizona and New Mexico a few months later. As he noted in one of his reports for the Times from that trip, “One of the regrets of my lengthy paseo of two years ago was my lack of ability to bring away pictorial reminiscences of the countless places along the road.” He had resolved to “learn light-writing — the expressive name which photography has borrowed from a language that knew nothing of these later wonders” so that wouldn’t happen again.

Recent advances in technology had paved the way for his photojournalistic forays. The dry-plate process perfected over the previous decade unchained photographers from darkroom wagons of the sort that Mathew Brady had to haul around during the Civil War. The wet plates Brady used had to be made shortly before exposing them and developed soon after. By the 1880s, dry-plate negatives could be purchased in bulk and stored for months. Lummis carried 90 plates with him on his 1886 reporting trip. He could go practically anywhere he cared to lug his Dallmeyer lens, camera, and tripod, a kit that tipped the scales at a mere 40 pounds. With a shutter speed of one-twentieth of a second, he could take reasonably sharp action shots of Indian dances.

Capturing sometimes unwilling subjects was another crucial photography skill that Lummis perfected. Writing for the Times from New Mexico in 1887, he observed, “For these Pueblo towns one should have a lens which will focus itself, adjust a plate and make an exposure in about the millionth part of a second.” His appearance with a camera “was the signal for such a scamper as nothing else short of a pack of wolves would be likely to cause.” So he had to content himself with photographing buildings and then “planting the camera in some obscure corner, focusing it down the street and waiting for the unwary to happen along.” Plying subjects with tobacco — or candy for the children — also worked. In Isleta, the handouts he liberally distributed to ingratiate himself with his new neighbors, who were initially wary of the strange white man in their midst, earned him the nickname Por Todos, “for everyone.”

Lummis put his photographs to a number of uses. In Isleta, when he was still making a living as a freelance writer and starting to supplement that with occasional sales of Indian blankets and other artifacts, he took to mass-producing cyanotypes of some of his most iconic Southwestern images. The simple, inexpensive, and forgiving process was well-suited for his circumstances. Sunlight and well water were all he needed to transfer his photos to blueprint paper from his humble quarters in Isleta. He and Eve mass-produced postcard-sized cyanotypes by the hundreds, which he sold to dealers of Western curios.

Lummis also employed photographs to garner support for some of his civic crusades, including an Indian rights organization called the Sequoya League. Some of his images, and the works of other Southwestern photographers, were used to produce hand-painted lantern slides that he projected onto screens at public meetings to rally support and raise funds.

In his years as a magazine editor, he used photography to help introduce the nation to the wonders of Southern California and the newly accessible Southwest and to illustrate the hard-hitting pieces he ran about, among other things, the latest perfidies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. One such investigative series, illustrated with photographs by the Southwestern photographer Adam Clark Vroman, stirred up national opposition to a directive from Washington banning Indian dancing and forcing Indian men to cut their long hair, which was being brutally enforced on a Hopi Reservation in Arizona.

Lummis helped get that order overturned with an assist from President Theodore Roosevelt. The two had crossed paths at Harvard and later struck up a correspondence when Roosevelt was writing a history of the West and occasionally sent questions to Lummis. Shortly after Roosevelt became president in 1901, he invited Lummis to the White House to offer his views on Western policy, the first of half a dozen meetings Lummis would have with the president.

He was careful not to overwhelm the upbeat tone of his magazine, and its focus on the beauty and romance of Southern California and the Southwest, with disturbing investigative pieces. But along with columns extolling the climate and photos of cherubic children in the buff surrounded by flowers enjoying the balmy delights of a Los Angeles winter, Lummis wasn’t averse to running pieces that made his readers squirm. “This little magazine tries to be popular enough to live and substantial enough to deserve to live,” he explained in a letter to a friend. “We believe it a magazine’s duty to teach as well as to tickle.”

Much the same could be said about Lummis himself. His eccentric behavior and ostentatious attire were partly the mark of a showman seeking to sell articles, magazines, and books. But it was also a form of personal protest against silly prejudices toward people who are different, which was at the root of the injustices he spent his life fighting.

Mark Thompson’s book American Character: The Curious Life of Charles Fletcher Lummis and the Rediscovery of the Southwest won the 2002 Spur Award for Best Biography.

From the February/March 2017 issue.