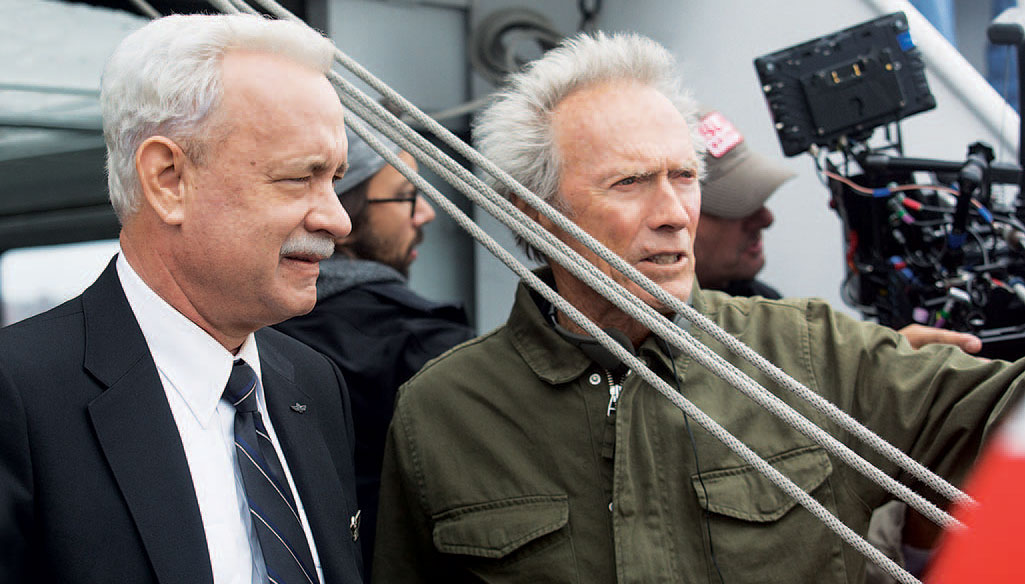

Clint Eastwood directs Tom Hanks as Capt. Chesley B. Sullenberger in Sully, a new movie about the miraculous plane landing that made the Texas-born pilot the Hero on the Hudson.

When I was growing up in a little Iowa town, every kid I knew wanted to be Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, or some other silver screen hero, leaping off galloping stallions onto teams of crazed horses to stop runaway wagons and save pretty damsels.

On January 15, 2009, Capt. Chesley Burnett Sullenberger III, who grew up in a little Texas town and had his own cowboy heroes, totally trumped our runaway-wagon fantasies when he miraculously landed a badly damaged US Airways Airbus 320 onto the freezing waters of New York’s Hudson River. He saved the lives of all 150 passengers and five crew members. Like a good old-fashioned western, it captivated the country with the drama of the rescue and the skill and grit of the protagonist pilot.

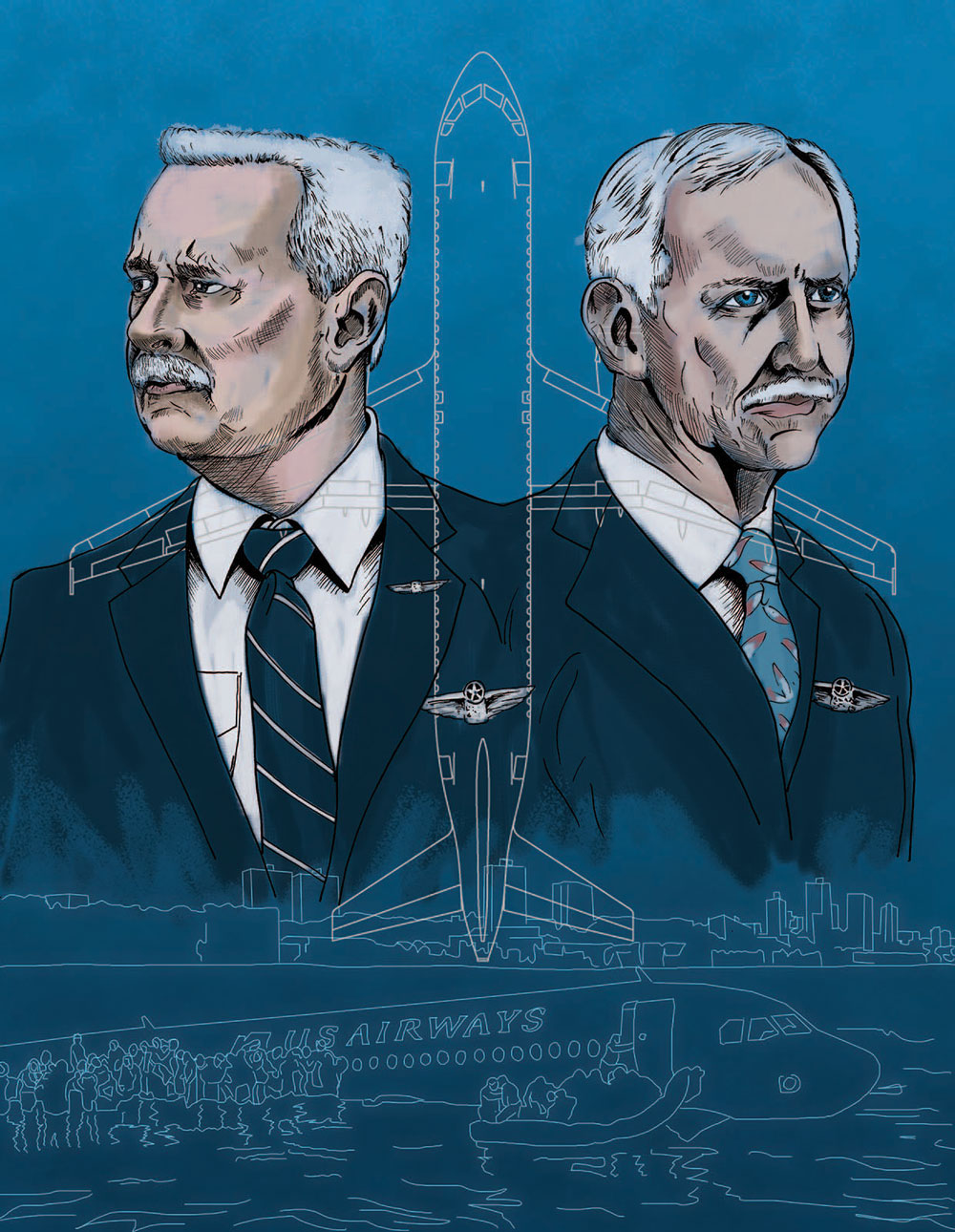

The feat was hailed as “The Miracle on the Hudson,” and the pilot known as Sully became an instant American icon. Now, fellow icon Clint Eastwood has made a movie about the man and the miracle. Sully, starring Tom Hanks, is due in theaters on September 9.

The son of a World War II veteran, Sullenberger grew up 10 miles outside of Denison, Texas, a rural town 75 miles north of Dallas. “I had a lot of movie and TV heroes when I was a boy,” he recalls, “actors like Jimmy Stewart and Gary Cooper and several TV heroes like the Lone Ranger; Sky King, who chased bad guys in his Cessna 310; and Rowdy Yates from Rawhide [Clint Eastwood’s career breakthrough role].”

The third-generation Sullenberger from Denison, he grew up steeped in western movie and TV heroes, Texas values, and Lone Star traditions. “As a kid, I wore the cowboy boots and the cowboy hat, and we kept an 1873 Winchester repeating rifle and a nickel-plated Colt single-action revolver in the house.”

More than the trappings and regalia, Sullenberger believes his rural Texas upbringing helped him develop character and integrity. “The size of the community and the post-war Eisenhower era made it a very safe, stable environment that promoted a real sense of community,” he says. “We talked to and interacted with our neighbors, which people don’t do so much today. We were raised to be self-sufficient, yet to also count on each other and be held accountable by the community to do our part.”

From the time Sullenberger was out of short pants, he never wanted to be anything but a pilot. He learned to fly as a teenager from instructor L.T. Cook Jr. in a single-engine, tail-wheeled two-seater. “His teaching was the foundation for everything I learned about flying and safety thereafter. He drummed it into me that the aircraft had to be an extension of myself — and that I must always have a situational awareness of where the aircraft is, the altitude, the airspeed.

“He emphasized that I must be in control of and never at the mercy of an airplane. Those lessons were vividly present with me in that cockpit on Flight 1549.”

After graduating as an Outstanding Cadet from the Air Force Academy and flying F4-Phantom fighter jets for his country, Sully went to work for Pacific Southwest Airlines in 1980, which was merged into US Air in 1988, later to become US Airways. He flew pretty much without incident until that fateful day in 2009, when, with 26 years of captain’s experience under his belt, he took off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport bound for Charlotte, North Carolina.

Almost immediately, his plane struck a large flock of Canada geese, whose feathers lodged in and disabled both engines, causing one to catch fire. He was at the controls of a 151,000-pound airplane that had exactly zero thrust. A passenger described the sound in the engines like that of tennis shoes knocking around in a clothes dryer.

Sullenberger would later say in a 60 Minutes interview, “It was the worst, sickening, pit-of-your-stomach, falling-through-the-floor feeling I’ve ever felt in my life.”

This is where the years of training and the thousands of hours of flying — and Sully’s inherently calm demeanor — took center stage. The duration of the flight was a mere five minutes, only three and a half minutes from the time he struck the birds. He had to make exactly the right decision and make it fast.

He says the discipline he had developed since he was a boy and the crisis-management skills he learned along the way were key factors that pulled him through that day. “You have to have team skills, develop great communication, and have a plan you can put into place in any crisis.

“If you’ve already done your homework and built your team that way, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel; you just have to put the last few spokes in place, which is what we did on the Hudson that day.”

Sully had never trained to land on water — nor has any pilot, because no such simulators exist. “Yet we had trained so well to have a shared responsibility for the outcome that my co-pilot, Jeffrey Skiles, and I were able to communicate wordlessly. He saw what was happening, he heard me on the radio, and he knew exactly what his part would be in this landing.”

They were past the point of no return to LaGuardia and too far from New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport to land safely without a great risk of killing the passengers and people on the ground. So it was the cold, dark waters of the Hudson or nothing. “You know, from the outset of that accident till we landed, I never thought I was going to die that day,” Sullenberger says. “I just wasn’t sure at first how I was going to pull that off.”

Most forced water landings end catastrophically, but Sully and Skiles had no choices left, and they ditched into the Hudson River unpowered, not unlike a gigantic glider — barely missing the George Washington Bridge because of Sullenberger’s skillful maneuvering. He also knew that if he didn’t come in at exactly the proper angle, or if he let the plane stall, it would hit the water in a way that would break it into pieces and likely kill everyone.

It was an absolutely perfect landing. But the miracle was only half over. Sully and his crew quickly evacuated passengers onto the wings as water seeped into the cabin from a leak in the tail. “I thought about what my father had always said about being responsible for others, and that’s why I went back into the cabin twice to get a head count,” Sully reflects. “I had never trained to do two walk-throughs, but I couldn’t exhale until I knew everyone was safely out of that plane.”

While no one knew it, within 26 minutes, that plane would fully submerge.

Rescue crews in ferry boats and helicopters came swiftly and in the nick of time. With the plane sinking and the water temperature barely above freezing, all passengers were rescued. Sullenberger was the last one off before the Airbus submerged.

Now, seven years later, Clint Eastwood’s movie Sully has brought this intense drama to the silver screen. The pilot, who is now retired from flying, and his wife, Lorrie, spent a handful of days on the movie sets, and Eastwood visited Sully at his home near San Francisco prior to filming. Sullenberger immediately realized that Clint “was very passionate about the project and that my story had found a good home.”

Meeting later with Hanks and going over the script together, Sully realized the actor would be a great fit. “He’s like the Everyman of acting and can adapt to any part. There was an additional connection between us because I had met Capt. James Lovell, the astronaut that Hanks played in Apollo 13.”

Sully was particularly impressed to see firsthand that the director’s reputation for efficiency was well-earned. “I was amazed,” he says. “Rarely did he have to do a second take.” He was also on the set when Eastwood filmed rescue scenes with passenger actors on the wings, on Falls Lake at Universal Studios, an artificial lake where many movie scenes have been filmed. Hanks commented to Sully that day, “This is like being on the set of Ben Hur in the 1950s.” His point: It’s rare that something so realistic is done in films today, when most every special effect is computer-generated.

Eastwood says he was attracted to this story for several reasons, not the least of which was how the tale signifies American heroism — a yarn, in spirit, not unlike that of some western heroes Clint has played.

Coincidentally, while in the military in 1951, Eastwood had also been a passenger on a flight that was forced to ditch in the water — in the Pacific off Point Reyes, California. “I was terrified, and it was a helpless feeling, so I knew what those passengers on Sully’s flight must have experienced,” he says. “Nobody ever gives you preflight instructions about what to do once you are in the water or standing on wings clinging to the hope that you’ll get rescued.”

While shooting Sully in New York, Eastwood was touched by how many New Yorkers expressed their appreciation that he was making the movie. That heroic landing was something that had made them all feel intensely proud, especially with the memory of 9/11 still fresh in their minds. “Like with many events in history,” Eastwood says, “many people remember where they were and what they were doing when Sully Sullenberger pulled off that landing.”

When he first considered the project, Eastwood didn’t know all the circumstances, including that the National Transportation Safety Board was actually scrutinizing Sullenberger over the landing — a normal procedure for the NTSB — and putting him through a “mini trial.”

“He felt conflicted,” Eastwood points out, “because there was some doubt in the beginning that he could have made it to some other airport. But there was no way he could have. He did the absolute right thing to save those lives.”

Eastwood had been called to testify at the hearing about the flight he was on in 1951 and still has a copy of the interrogation of that pilot. “They really ran that pilot over the coals. That’s what they do.”

Eastwood says he found Sully to be “a very humble man, yet extremely confident in his abilities. Tom Hanks is that same kind of fellow. I had never directed Tom, but I’ve known him for a long time. He has that same calm demeanor and is also about the same age as Sully when Sully made that landing.

“Tom just took on Sully’s demeanor, so it wasn’t a big chore to direct him. We were lucky to get him for the part.”

As for his own connection with the pilot, Eastwood and Sullenberger both have survived a near-miss airplane accident landing. And, it turns out, they idolized some of the same western heroes as kids — primarily Gary Cooper and Jimmy Stewart.

Eastwood can’t name a favorite movie of his own or anyone else’s, but he has an interesting take on it. And his attraction to the archetypal principled hero goes way back. “A movie might be like a song you listened to on the radio. It might remind you of a certain period of your life. I put [the 1941 Cooper classic] Sergeant York way up on my list because it was the first film I ever saw with my dad. It was a great movie, but that makes it even more endearing to me.”

Eastwood feels good about Sully, but admits he can’t predict how the public will receive his films. “I never knew Unforgiven or Million Dollar Baby would be so well-received or win those Oscars. I just knew I liked those films once they were finished, and that’s all I can say about Sully. I hope people take to the film and enjoy it. I’m quite proud of it.”

But just because the story’s been committed to film doesn’t mean Sullenberger is going to ride — or fly — off into the sunset. He retired as a commercial pilot but traded one profession for others. Shortly after the emergency landing on the Hudson, he co-authored his autobiography, Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, which became a New York Times bestseller, and has followed it up with a second co-authored book, Making a Difference: Stories of Vision and Courage from America’s Leaders. He’s also an aviation and crisis-management consultant, a speaker, and an advocate for an array of good causes.

In the end, Sullenberger believes that heroes and leaders are not born, but made. “I do think character is learned, that it can be taught. In this winner-take-all world, there are still things we must do to put our own needs aside and do things for others.

“It all starts with core values that frame your decision process and make those values a daily reality. I believe that if you walk the talk, people notice, and you can lead by example.”

Dan Gleason, an award-winning magazine writer and author, teaches graduate creative writing at Southern New Hampshire University in Hooksett, New Hampshire. Learn more about Capt. Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger online.

From the October 2016 issue.