He’s been one of our best-loved artists for more than 100 years, and, as expert Peter H. Hassrick knows after editing the new definitive collection of his “flat” art, there’s still more to glean about Frederic Remington.

Peter H. Hassrick likes to joke that if he’d gotten a royalty deal on his first Remington book, he could have put his kids through college. That volume about the collections of Amon Carter and Sid Richardson reaped huge sales for an art book — an indication of just how beloved the painter, illustrator, and sculptor is. Decades later, Hassrick, who is director emeritus and senior scholar at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, is still digging deep and finding more. Which brings us to his latest achievement: editing Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné II (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), which catches Remington lovers up on newly discovered and newly authenticated works since the first edition in 1996. C&I talked with Hassrick about the project and the 19th-century giant who remains one of the most popular Western artists of all time.

Cowboys & Indians: What exactly is a catalogue raisonné?

Peter H. Hassrick: It’s usually a chronological pictorial assemblage of an artist’s life’s work. Sometimes it’s segmented into sculptures, prints, paintings. This new book is just Remington’s flat work: his paintings, drawings, and watercolors. ... It was a compelling way for those of us interested in Remington scholarship to make a contribution back in the ’90s [when the first edition was published] about who this Remington guy was and make a better determination about his motivations, directions of his work, how he developed or changed or improved over the years. The Buffalo Bill Center of the West had two great partners in the Catalogue Raisonné II project: We collaborated with the Stark Museum [of Art], a program of the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation in Orange, Texas, and the artist’s estate museum, the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York. We couldn’t have done this without them.

C&I: That first edition came out in 1996. Why another one in 2016, 20 years later?

Hassrick: There are 3,000 flat works by Remington. Of those 3,000 works, we were able to identify 1,000 originals. Many were illustrated. Even if we didn’t know the original, we could go to Scribner’s, Collier’s, Harper’s, the important periodicals of the day, to see the illustration — this is what it looked like when first created. That first edition was two volumes’ worth (469 pages per volume). We didn’t leave much out. In the interim, we found that many of the paintings had changed homes and we discovered over 200 new items. There are two types of “new”: One is, This is a painting that we only had the illustration for and we now have the original. The second is a piece that was never illustrated, but we determined that we had discovered a new piece that was previously totally unknown. About 200 had come to our attention; several hundred others have changed hands in the interim as well. It seemed reasonable to do a new publication, an updated catalog. For the overflow material, the first edition used CD-ROM, which is yesterday’s tech. Now if a new work comes to our attention, we can insert it into the catalogue raisonné online. Also, in the original catalogue raisonné, the thumbnails were all in black-and-white with about 100 of those replicated as color plates. We were able to add new pieces and get more in color than we had before. Now nearly half of the known works are in color instead of about 100 of those replicated as color plates in the original catalog.

C&I: That’s clearly an indispensable tool for experts. What about your basic Remington lover?

Hassrick: For dealers and scholars, it is kind of a rarefied tool. What about the broader public? The University of Oklahoma Press wanted a new book with new author essays and different perspectives. Remington, still to this day, is one of the most popular Western painters going, and there’s a good deal here for Remington’s public. The introductory essay by me talks about the process of authenticating. There’s a committee of experts who have experience in Remington’s artwork who come together once a year; pieces that have come to the surface are vetted by that group. Remington is one of the most faked of all American artists. On an average authentication day, the committee might be looking at 25 pieces. Twenty percent will turn out to be original. The rest will be one of a variety of fakes: a copy that’s signed fraudulently, a work by another artist where the original signature’s been painted over, or an absolute fake and signed Frederic Remington — all of which are frauds.

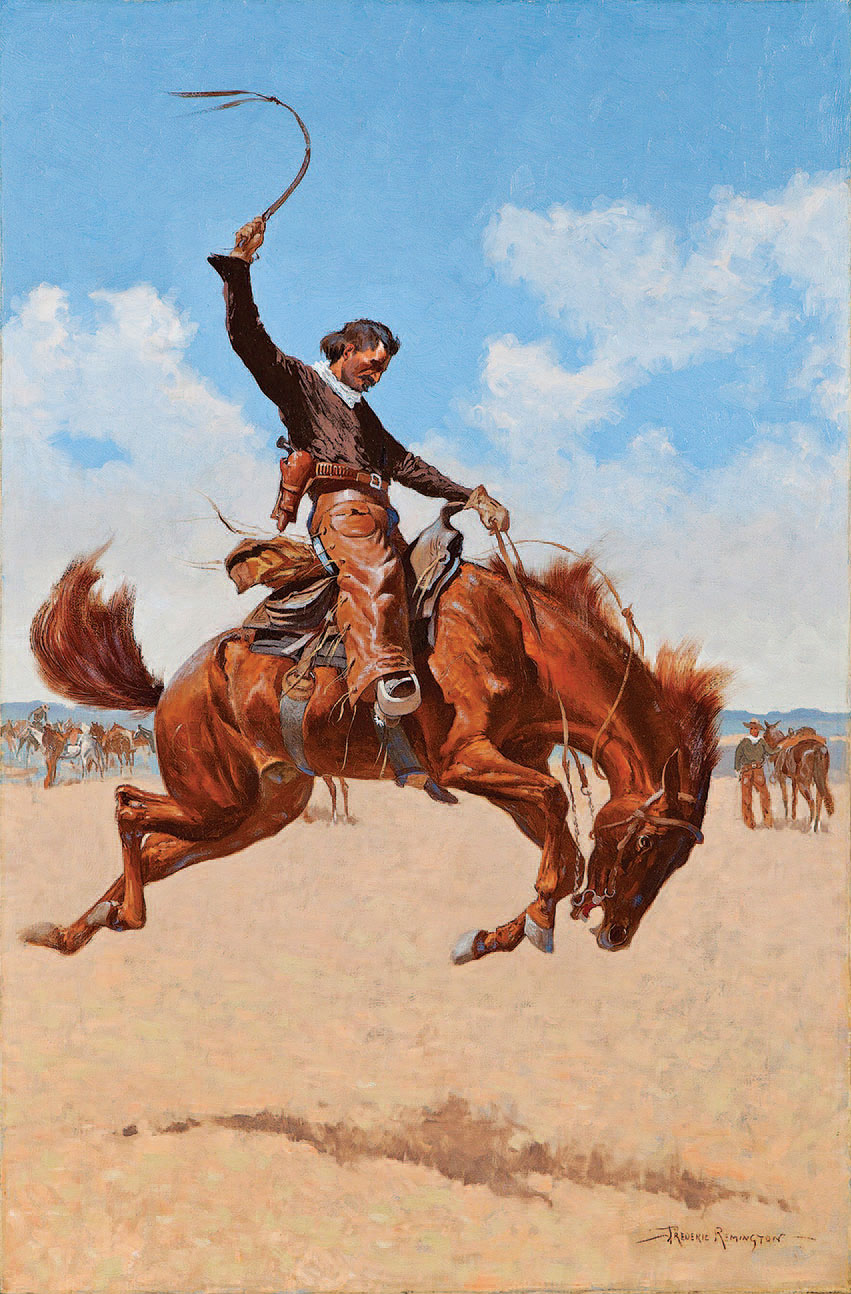

Another of the essays is about Remington in Taos, New Mexico, and there’s one on Remington as an equestrian artist. On his tombstone, he wanted “He knew the horse.” Though that didn’t ultimately end up on his tombstone, he did have a national reputation as a painter of horseflesh. There’s another essay on Remington and Howard Pyle, a great illustrator who’d studied art in Philadelphia and who, along with Remington, was one of the most popular of his day. When illustrators got popular, they were the rock stars of the day.

C&I: But he wanted to be regarded as more than an illustrator. ...

Hassrick: Remington’s early works were illustrated as wood engravings. In 1890, the halftone process came into play, so his illustrations were reproduced photographically. In the early 1900s, color came in and magazines like Collier’s became famous for their color images. Remington worked for them for about five years doing color oils reproduced as magazine spreads. The good news there was he had major stature as an illustrator; the bad news was that illustration was deemed secondary to painting. But working for Collier’s, he could invent his own narratives and his paintings were gradually regarded as fine art.

C&I: We know he achieved that stature, but did he?

Hassrick: He left Collier’s, where he had a very lucrative contract, to devote the remaining two years of his life (1908 – 09) to painting and sculpture. His annual exhibition was at Christmas at Knoedler [& Co.] gallery in New York, which was a prime venue for American artists of the day. He began to get recognition that he was no longer just an illustrator — he had really joined the ranks of the fine artist. But at the age of 48, in 1909 at Christmastime [December 26], he died of the effects of a burst appendix, peritonitis. His career was cut tragically short.

Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné II, edited by Peter H. Hassrick, is available through University of Oklahoma Press and on Amazon.

From the August/September 2016 issue.