The award-winning painter has gained fame for capturing the essence of life in the American West and the tropics — different versions, for him, of paradise.

As a kid growing up in Solana Beach, California, Michael Cassidy was the self-reliant sort. As an acclaimed artist living in Bend, Oregon, he maintains some of that independent streak — and a certain casual philosophical bent. “I’ve never liked hurrying or desperate running for a buck,” he says. “If I told you how many times I had the opportunity to sell a painting or make a buck and went fishing instead, you’d think ...”

You’d think, This is a guy who definitely paints to his own muse. “I embrace country sorts of values — whatever you see in Mackay, Idaho, or Bondurant, Wyoming. Salt-of-the-earth sort of stuff. I didn’t appreciate these things when I was young, but now I do. People in those places would give you the shirt off their back and would do anything to help you.”

His attitude informs his art. No airs here. In keeping with country values, Cassidy advocates a slowed-down, simpler life. All the better to check in with the Big Inspiration in the Sky for his painting. “Why would I spend all my waking hours just to have a fancier whatever and as a result you’re going too fast? God works at a different speed. When you’re going slow and have no agenda, things can happen. You’ve got to be available and willing. You’ve got to ask yourself, What’s my value system? What am I chasing? Am I putting my energies into a harvest that will have a lasting value to it?”

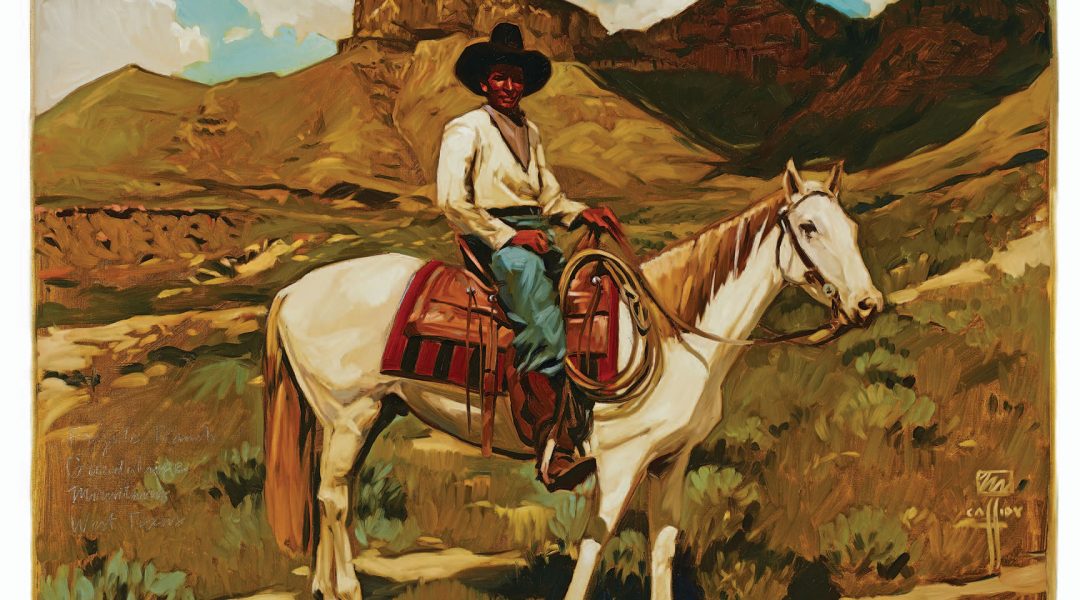

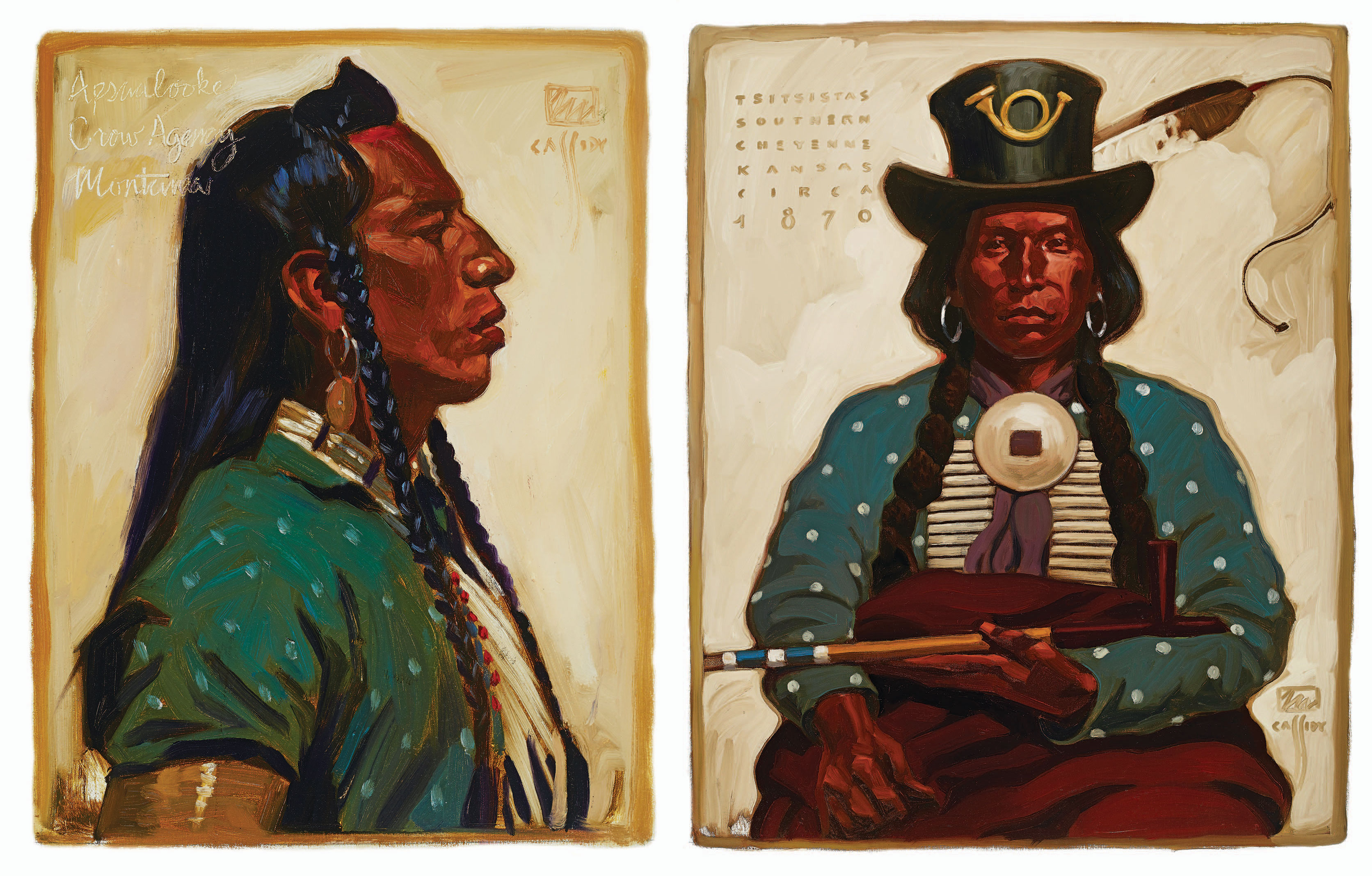

Currently among the most collectible in the Western genre, Cassidy this day is putting his energies into exploring concepts for new paintings by going through pictures he took last year on the Crow Indian Reservation. “We shot a couple thousand pictures. I do trips like that a couple of times a year, usually in spring and fall. Wyoming and Montana are beautiful, but, boy, it’s a long, cold winter and boiling hot in the summer. I like to go when there’s still a little snow on the peaks and everything is green. We’ll take two-week road trips and other shorter trips, like maybe fly into Albuquerque [New Mexico] and rent a car and drive from Santa Fe into Colorado.”

The paintings that come out of these travels are more than mere pictures on canvas. For Cassidy, they’re nothing less than intimations of paradise. “I love the idea that there’s more than the here and now. The value of art is that it’s that signpost. ...”

A signpost people are willing to lay down good cash for. “It blows my mind the amount of money people pay for artwork, even mine, but I realize why they do it. We are all really looking for home. People put a painting on a wall and it’s a reminder. A painting is an ideal — a beautiful painting has this romantic allure and magic to it. Those are the characteristics of home and heaven. We see little indicators of it in those infrequent moments in our lives when we feel that it couldn’t get any better or more beautiful than this. They spend all this money to put it on the wall and are not even conscious of why. If through my painting I can make a relationship with someone, I have an opportunity to be an influence.”

In other words, to help a home hang a little heaven on the wall.

Cowboys & Indians: How did you get from South Pacific and surfing subject matter to cowboys and Indians?

Michael Cassidy: I was interested in the South Pacific and Indian horse culture from the time I was a kid. I was just born with those two main interests. I read everything I could get my hands on. As soon as I had a driver’s license, I would go to the library at [University of California] San Diego and spend all day there looking at old books. I had some introductions to galleries in Hawaii from friends, and I did illustration work for Quiksilver, Patagonia, Hawaii Visitors [and Convention] Bureau, United Airlines, etc. I did a few covers for books on Indians but never brought any of my Western paintings to the marketplace until the last couple of years. We moved to Bend, Oregon, nine years ago, and since then the majority of my easel paintings are Western subjects. It wasn’t really a situation where I had a whole new subject matter; it was more the fact that I had places in the West I wanted to go that are fairly close to where I live now.

C&I: Where in the West do you specifically like to travel for your artistic research and subject matter?

Cassidy: There are so many places, I wouldn’t know where to begin. Anywhere you can see the “bones” of the country is good. I avoid tourist areas and try and stay on the back roads as much as I can. I have more maps than you can shake a stick at. I look at Google Earth and try and see what the country is like, then roll the dice and go. You wouldn’t believe where you can go in the West with a four-wheel drive and a good map.

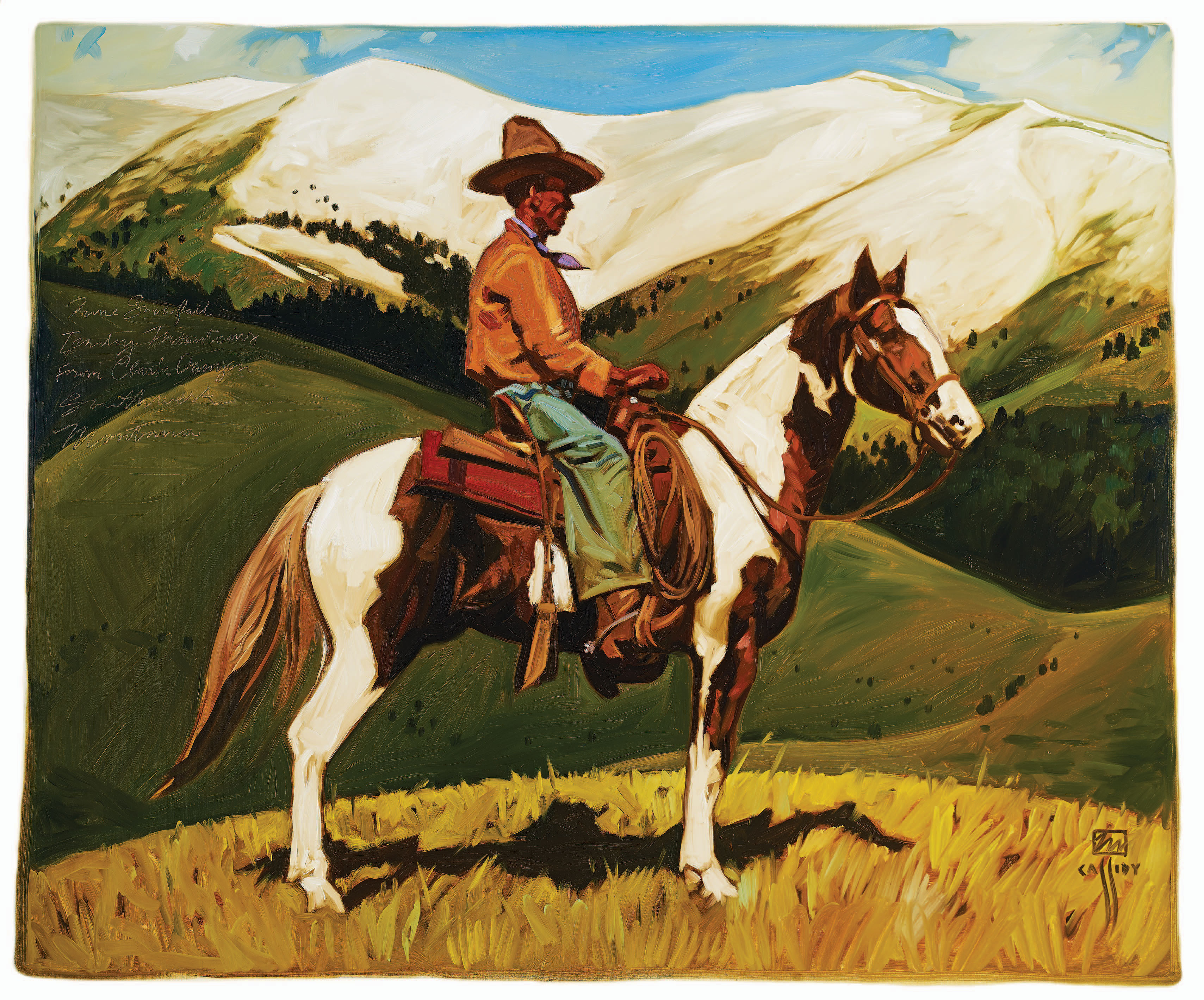

I don’t want to be too specific about my honey holes, but I’ll tell you about one. A few years back I went by horseback up into the West Elk Wilderness every year for a week at a time with my buddy Steve Duffy, who’s one of the best falconers on earth, and an old cowboy named Dellis Ferrier, who’s been going into those mountains for 60 years, since he was 8 years old, running cattle and guiding hunters. He knows more about that country than anybody alive. One of the things that caught my eye was the old Ute trails you can still see. The white-man trails zigzag up and down the hills; the Ute trails go straight up and straight down. Can you imagine what kind of horsemanship that took with no stirrups to stand in? It’s really steep country. Their horses were extensions of their own bodies. In the time we spent up there hearing Dellis’ old stories and him showing us the old Ute camps and rustler’s cabins, we never saw another human being. Too steep and too long and too remote a trail for anyone to hike. We rode as high as 12,000 feet. Just to find the trailhead was an adventure, and we knew the way! Really special place.

I spend a lot of time in the Beaverhead country in southwest Montana and eastern Idaho. It’s beautiful country and sparsely populated. Nobody really goes up there because it’s not on the way from one place to another and there’s no tourist spots. I like empty country. Northern Nevada is great. Maynard Dixon country — I like the Sangre de Cristo Range in southern Colorado-northern New Mexico. Anywhere in New Mexico is great. I like the Upper Green River area on the west side of the Winds. That was mountain man country. I reread Osborne Russell’s Journal of a Trapper last year while we traveled the area. I like to read the history books, get a map, find these places, and then go there and explore. I stop at one-horse towns, old graveyards, battlefields, historical markers, etc. Me and my manager, Pete, are road dogs. We bring good cigars, some single malt scotch for the campfire, and look for visual golden nuggets and whatever is around the next bend.

C&I: What attracts you to Western and Native American culture?

Cassidy: What it represents. The story. Man was made with a thirst for beauty, romance, adventure, and love. The cowboy and Indian lived in a land that humbled man. There’s a lot to be said for that. Humility is the beginning of wisdom. They saw beauty a lot more frequently than most of us do today. Just living in those times was an adventure on a daily basis. Read mountain man Osborne Russell’s Journal of a Trapper for a little taste. They had a different set of values than the popular culture represents today. God, family, and moral values were more important. Watch any old western. There’s always a moral to the story. They needed faith to survive and scratch a living out of a harsh country.

I admire the way the Plains tribes fought for their way of life. Freedom meant everything. How many people today are willing to put their life on the line for a set of principles? The old-time cowboys and Indians were hard, tough, self-reliant people. Their word was their bond. They were humbled by a land they knew was stronger than they were. They knew there was something or someone greater than themselves.

There’s a reason that cowboy and Indian culture still resonates with people. They recognize a set of values that stays the same no matter what changes in popular culture. In my opinion, our modern culture is running down — too much time in front of the TV or with our faces in a cell phone. The values those old-timers had aren’t “old.” Most of us in “flyover country” still have them. I paint the West because I believe in what it represents.

C&I: How do you go about making sure you get it right?

Cassidy: I do my homework. Lots of research (reading, old photos, etc.) to start with, and then I go and visit the people and places I want to paint. I spend a lot of time on the road. You have to spend the time to figure out what the essence of the story is. Sometimes that can take years. I’ve lived in Oregon for nine years, and I’m still trying to figure out what the story is. What makes it unique? I think I understand Montana, Wyoming, etc. Oregon I still haven’t figured out. It takes some thinking and looking around until you stumble on something that speaks to you. You just have to put in the time and the miles.

C&I: You’ve painted a fair amount of surfing, and you’re a surfer yourself. What, if anything, do surfers and cowboys have in common?

Cassidy: Surfers learn pretty quick that the ocean is a lot more powerful than they are. If you don’t respect it you get an ass-kicking (actually, you get that anyway). When the surf is really big, they say there are no atheists in the impact zone. Everybody prays when they get caught inside. Near-drowning is not fun. Surfers are observers of nature like a cowboy or an Indian. When a city person goes to the beach, they see sand and water. A surfer knows what the tide is doing, the wind direction, how big the swell is, what direction it’s coming from, whether the storm generating the swell is close or far away, etc. Most of this they know at a glance. Extrapolate that to what a cowboy or an Indian knows about their own country. Country people sit still long enough to watch and learn. City people don’t sit still. Modern culture doesn’t sit still. Both surfer and cowboy are gluttons for beautiful places at the edges of civilization. They’re awed by that beauty, and it refreshes their soul. They like to see what’s around the next bend and share the adventure with a friend.

C&I: Both Native Americans and Pacific Islanders have provided you with rich subject matter. Any similarities there?

Cassidy: Any people I’ve ever met that live in a place where nature dominates man have many of the same characteristics. They have a slower pace of life. They’re more family-oriented. Experience is more important than material goods. They share whatever they have. There’s usually a spiritual attachment to the land. Nobody is in a rush. There’s time to think. That appeals to me. I choose not to live at the speed of modern times. Less is more. Slow down — you learn more.

C&I: What specific tribal cultures attract you?

Cassidy: Different tribes for different reasons. The Sioux and Cheyenne for their willingness to fight for their land even though most realized they couldn’t win. The Shoshone and Flathead for the wisdom and prescience to make the pioneers their friend and not an enemy. No Shoshone or Flathead ever killed a pioneer. The Flathead were a very chaste and self-disciplined people. I spend a lot of time in the country where they lived. The Comanche for their horsemanship. Certain personalities I find interesting. Washakie, for example, lived 100 years from [about] 1800 to 1900. He ruled the Shoshone for more than 60 years. Most tribes didn’t have a head chief that everyone followed. When he was near 70, some young Shoshone braves were complaining about the idea of ending intertribal warfare (which was how they earned their status in the tribe). Some of them called Washakie an old woman. He said nothing and then left camp for two weeks. When he returned, he dropped a half dozen Sioux scalps at the feet of his detractors without a word spoken. [At] 70 years old. All criticism stopped from that moment forward. Another time, Washakie dealt with a domestic violence issue by a Shoshone man who was beating his wife by simply walking up and shooting the offender in the head. He told the reservation minister who had made him aware of the problem, “You no worry. He no trouble no more. I fix him.” The Sioux said Washakie was the single greatest warrior they ever fought. Not a whole lot of attention is paid to him, but what a story. He lived through the entire 1800s and saw it all.

An interesting footnote to this is that those tribal members who know will tell you that individual tribal characteristics — some for better, some for worse — still exist. [They’re the] same characteristics now as back in the old days. I’ve heard some really funny and really crazy stories I can’t repeat. Suffice it to say, people are people wherever you go.

C&I: Do western movies influence your work?

Cassidy: I think like anybody else I’ve been affected with a romance with the West that in part comes from westerns. I like the fact that the old westerns always had a moral to the story. I’ll watch any western with Robert Duvall in it. He just gets it. Lonesome Dove was probably my all-time favorite. I like the old spaghetti westerns even though they were made in Spain. What’s odd is that the music for those movies and old-time surf music are almost identical. There was a made-for-TV movie called The Good Old Boys with Tommy Lee Jones. He does a classic West Texas cowboy as good as it could be done. Wish I could get my hands on it. [Note: The movie is manufactured on demand when ordered from Amazon.com.]

C&I: Your biography mentions surfing, travel, faith, and family as your touchstones. Tell us more about that.

Cassidy: Surfing. There’s nothing quite like it. You’re riding a band of energy that moves through the water generated by wind that’s come hundreds of miles across the ocean to break on the reef you’re floating over. It takes years to learn to do well. If you didn’t start as a kid, your chance of getting really good at it is very slim. The fact that many of the best waves in the world are in drop-dead beautiful locations far from civilization makes it magical. I’ve ridden waves in the Mentawai Islands off Sumatra [in Indonesia] with Stone Age tribesmen paddling canoes in the channel. Surfers are traveling fools. They will go anywhere no matter how remote if there’s good surf to be had. The adventure is half the fun. If the surf is good, it’s gravy.

Travel. I’ve been so enriched by the people and places I’ve been blessed to see. It would take a book to describe it (actually, I’m working on one called Eden). You adopt whatever you see that’s good into your own lifestyle. I wish young people had the same opportunity I had to travel. You learn much more than you would ever learn in a classroom and make lifelong friendships. My lifestyle is an amalgamation of all those places. I’m part Hawaiian, part Fijian, part Mexican, part cowboy, etc. That’s real wealth to me.

Family. The Hawaiians have a thing called ohana. It’s extended family. It’s based on relationship, not blood. As a result, I have a huge family and family members all over the place. At home I have my kids and a loving wife who puts up with my wandering without complaint. She’s learned to exercise faith in God being married to an artist. You never know where the next paycheck is coming from. They say God is never late but rarely early. When things are tight, that’s the time to give. It’s the opposite of common sense, but it works!

When you travel through the small towns I frequent, the farther you get from the big city, the more you see how important family is. The simple things in life matter a lot more. I live in “flyover country.” God and family are important here. Nowadays that makes you a rebel in the eyes of the popular culture. You’re mocked as a Bible-thumper or bigot or “bitter clinger.” A dumb redneck. Of course none of it’s true. People thought the same thing about cowboys and Indians in their day. Whatever way the popular culture goes, I tend to go the opposite way. I’ll follow the truth wherever it leads, whether it’s popular or not — no apologies.

Faith. I appreciate your asking the question. Most people avoid it like the plague. They’ll talk about anything except what really matters. As regards faith’s relationship to art: God made me an artist. I’ll be one for eternity. This is just the beginning of forever. I’m still a little child in that regard. There’s so much to learn, so many stories to tell. I realize that what an artist does is really crude in comparison to the 3-D ever-changing canvas that God paints every day, but he finds a way to use it. I believe the reason I’m a painter is to call attention to what God’s made and the signposts to heaven they represent. I can participate in the process of honoring him. He didn’t have to do that, but I’m glad he did. He made us creative beings. It’s mind-blowing when you really think about it. There are so many stories to tell you couldn’t fit them in a thousand lifetimes. I have so many projects I’ll never get to in this lifetime. There’s never any reason for me to be bored or without inspiration. God provides.

C&I: It’s a wonderful philosophy. Where in all that does paint actually meet canvas? What’s your studio like?

Cassidy: It’s the whole second floor of my house. I have a lot of room. Short commute. I work when the kids are at school or at night after they go to bed. It’s peaceful at night. There’s an office, a stereo, Ping-Pong table, pool table, a printer and computer, etc. It’s nice to be home where I can be with my family when I need to. I decided early on when my son was born that I would never tell my kids I couldn’t play with them because I had to work. Family comes before work. The older I get, the more I just want to paint. The last couple years have been my most productive to date.

C&I: Who are some of your teachers and inspirations?

Cassidy: John Singer Sargent and Joaquín Sorolla were inspiring for their technique — in my opinion the two best with a brush that ever lived. I like W.H. Dunton, Victor Higgins, and Ernest Blumenschein from the Taos school, and Maynard Dixon for the spiritual feel for the land that he had. I loved the illustration work of Maurice Logan. I like John Moyers’ work.

As far as a literal teacher, the most influential was “Cowboy” Doug Durrant. He was a drawing and painting instructor at Palomar College that knew everybody from Sonny Barger to the governor of Texas and everybody in between. He spent his summers in Alpine, Texas, driving the back roads, sketching in the daytime and shooting pool in the honky-tonk at night. He just had soul. That was the thing he taught me: Find out what the essence of something you love is, learn about it, and paint that. Pay your dues and tell the story in your voice. He was a good friend. He came to my wedding and my gallery openings. He was a champion of young artists. He retired last spring and passed away last fall. I miss him, but I’ll see him on the other side.

C&I: Do you abide by the philosophy that art should carry the message of the artist? What are you hoping to communicate?

Cassidy: I do. It’s important that an artist have a story to tell that has their stamp on it. You have to find out what that story is first; otherwise you’re just making a decoration. I think we have a story written in us from birth. It’s not, however, immediately apparent. It takes time and the experience of just living life to bring it out. You might be born with a gift for art, but that’s just a small piece of the pie. There’s big chunks of hard work, stubborn determination, and self-discipline you need for it to fully flower. Most people aren’t willing to do all that. They want it all now. It doesn’t work that way if you really want to make the most of what you’ve been given.

I finally figured out that my obsession with the South Pacific was an attempt to find heaven on earth. It’s a Garden of Eden thing. It took years to figure out there is no paradise on earth. I went to a lot of places. They all have fatal flaws — namely that you don’t get out alive. It always ends. Everybody is eventually required to check out.

What really matters is what the symbols of paradise stand for, where they point. Home. Heaven. You see the story of earthly paradise lost in a Tahitian girl’s eyes. You see it in the faces in the old photographs of Sioux and Cheyenne. We know we’re made for paradise and we desire it with all of our being. The truth is that what we see with our eyes is temporal. It’s what we don’t yet see that’s really “real.” The Indians understood this. That’s why they weren’t afraid to die. The cowboy humbled before nature sensed it. This isn’t home. It’s a hotel stay, if you will, but we see the signs of what’s to come in those magic moments in life that come all too infrequently. The more you go out looking for them and slow down long enough to see them, the more frequent they become. Cowboys and Indians saw magic all the time. To capture a small glimpse of that magic on a canvas is what I hope to do. If I can move someone to contemplate the things that last, the stories that never die, then I did my job.

Read more of the interview with Michael Cassidy.

From the August/September 2016 issue.