In Crow Fair, the Montana fly-fisherman, horseman, and writer treats his short story characters with the same empathetic tenderness he offers his own animals.

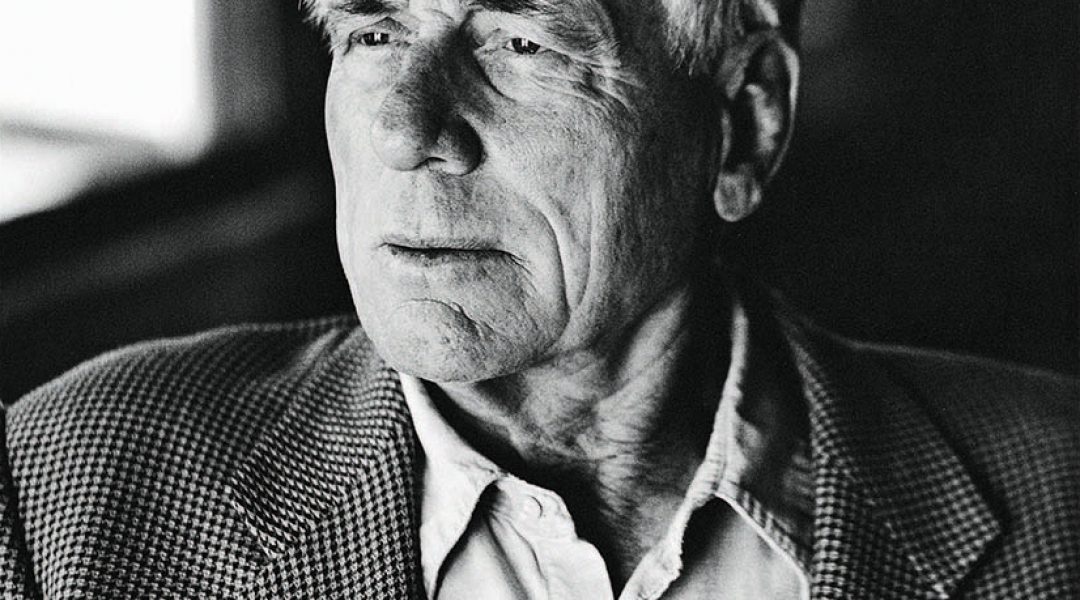

“No ideas but in things,” William Carlos Williams said, and although Thomas McGuane is one of our country’s most intellectual writers — a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, and before that a grad student at the Yale School of Drama — he is also if nothing else a man of things and a doer, not just a thinker. It is for this duality that I most admire him, though it is true as well that the pleasure I take from his sentences comes in a close second.

In between a life spent outdoors — ranching in Montana near Yellowstone country, fly-fishing, bird hunting (he’s also a member of the National Cutting Horse Association Members Hall of Fame and the Fly-Fishing Hall of Fame) — he’s written numerous screenplays and 16 books, including his most recent, the short story collection Crow Fair. McGuane credits his high book count — juggling that labor with all his other passions as well as obligations — to his Midwestern work ethic. People started working here, he says — in Michigan — “at the age of 6.”

He came West as a young man with a girlfriend whose family had a ranch in Wyoming that they let him work on. “I fell in love with it as soon as I saw it,” he says simply (he’s constitutionally unable to use a cliché such as love at first sight, even in speech).

Crow Fair harks in its precise imagery to Annie Proulx’s Close Range: Wyoming Stories. The stories are redolent with the tenderness of dismay at time’s great force, time’s great passage. The stories in Crow Fair don’t possess so much nostalgia or sentimentality as an admiration for the great crush of the world that so shapes each of us as individuals, and charts our identity as a species.

In “A Long View to the West,” a bedridden old rancher tells for perhaps the thousandth time the same familiar stories of yore to his son Clay. The father’s vignettes are rendered beautifully (no ideas but in things), as the son, rather than abhorring their maddening repetition, comes to realize they are treasure — though even in that repetition, the son finds the secondhand memories drifting away, as he himself forgets exactly how they went.

“The hospital sat right in the middle of the old Matador pasture, where the longhorns coming up from Texas had recovered from the long trail. Clay’s great-grandfather had been one of the cowboys, and the story was that when they first arrived the Indian burials were still in the trees, and the ground was covered with stone teepee rings. A picture of that first roundup crew, with the reps from five outfits lined up in front on their horses, was [Clay’s father] Bill’s most cherished possession, and he fretted constantly about its safekeeping when he was gone. He seemed to feel that no one in his family cared anything about it. That was probably true. Either that or they were sick of hearing about it.”

I can’t help but think McGuane’s long history with animals has helped shape him as a writer. He’s trained horses as well as bird dogs — always an ongoing process, for any bird hunter. McGuane favors the athleticism — the single-mindedness — of English pointers, though he babies all of his like little purse dogs; he refuses to take his beloved Judy out early in the season, when rattlesnakes are still active, saying that if something happened to her, “I would have to gas myself.” Of the difference between dogs and horses, he says that “compared to horses, dogs are lawyers.” Horses: “Every one of ’em is different. They really remember you.” He tells me about one horse he had not seen in years. He drove up one day to where the horse was, got out of his truck, and the horse spotted him and stared at him from half a mile away.

“They don’t love us the way dogs do,” he says. “They’re as wild as deer when they’re born. The thing that really characterizes them is innocent self-absorption”: a quality, it occurs to me, that typifies some of the drifting characters in his stories. Then he describes them further: “They rarely do anything bad or mean. But they can do terrible things if they’re frightened.”

Again, this describes some of the characters in Crow Fair perfectly. People definitely become frightened, most often by change: the loss of a relationship, the loss of a ranch, the loss of memory. In “The House on Sand Creek” — a complicated story of familial tension — the adopted child of a dissatisfied couple is briefly kidnapped by the babysitter, but the couple doesn’t press charges when the baby is found, and they let the babysitter have the child. It’s dark stuff, rendered with scalpel sentences and an irony of which Flannery O’Connor herself would be proud. No one story is fully like the others — which again, coupled with excellence, makes McGuane one of the most intelligent and interesting of our writers — but a not-uncommon motif is respect for old-timers who affect or exemplify a dignified leave-taking as the values and morals of their bygone world rush away. I remember hearing in an interview an idea that McGuane attributed indirectly to Shakespeare: “All literature is about loss.” I had never considered such a thing. I wanted to disagree with him. I went straight to my bookshelf, looked at my favorites. Loss, all.

McGuane still retains the stylish turns that so defined him as a young writer, but now he is quick to spot them and turn away from them, as if directly into the wind, away from snark and into a clean sincerity and an acknowledgment of the kinds of brutal truths the more manic of his earlier stories’ characters might have spent their entire lives trying to avoid witnessing. In those wild evasions, there was entertainment, but it was almost of a gladiatorial nature — like watching beetles in a glass jar wage their desperate struggles. In these new stories, the characters seem to be playing for higher stakes: They’re fighting not only for their own equanimity but also for the concerns of others. There’s a responsibility that is all the more personal and powerful in that it possesses no quality of preachiness, just an increased and larger awareness of the world beyond one’s own troubles and struggles.

To be clear, the mania inhabiting some of his more memorable characters has lost none of its fastball; the arcs of these stories are just shorter now. They meet their denouement much more rapidly, and with greater finality, greater punch. Time and again in these stories characters come up hard against diminishments coming from all directions. Describing a house two prospective buyers are viewing: “It was an absolute horror. Skinned coyote carcasses were piled on the front step, and a dead horse hung from its halter where it had been tied to the porch. Inside was a shambles, and there was one detail we couldn’t understand without the help of the neighbors: shotgun blasts through the bathroom door. Apparently Mrs. Old-Time Buckaroo used to chase Mr. Old-Time Buckaroo around the house until he ran into the bathroom, locked the door, and hid in the bath. The sides of the tub were pocked with lead.”

In “Hubcaps,” a boy stealing hubcaps is unloved and goes on to worse things. Not all of these are stories of mankind’s sweeter sentiments. Racism, particularly toward (but not limited to) Native Americans, is depicted with scathing, breathtaking accuracy of that cultural idiocy.

McGuane has had the opportunity to travel the world but says, “I’ve had more than my share of the world.” We talk about the sweet and peculiar brand of homesickness wherein, no matter that one has lived here for decades, it never grows old; indeed, the love of place increases each day. I remember being in France and being asked by his fans there if I knew him. Yes, I told them, he’s a good friend. He learned only one sentence in French, they told me: I miss my little pony, and I want to go home.

He loves animals, loves having them around the house. “Any animal will do,” he says. “I had a cockatiel. When it died, I was heartbroken for half a year. “I like to take care of things.”

This includes the land, treated lovingly in his prose: his beloved Montana, where, in Crow Fair, the beauty of that land is a salve for those who are living what are often torturous or lost or slowly losing lives of quiet desperation. McGuane passes on to me something he heard from filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola: “What’s the rush? You’re born and you die, and there’s that part in the middle.

“Just the other day, [my wife] Laurie came home from dinner in Livingston at dusk. We looked out at the hillside and watched two big buck antelope standing in the falling snow, and I felt so swept,” he says. “I fear not spending minutes here.”

Rick Bass is a Montana writer whose books include his upcoming short story collection For a Little While (Little, Brown and Company, 2016). Thomas McGuane’s Crow Fair (Knopf, 2015) is set for paperback release on March 8.

From the February/March 2016 issue.