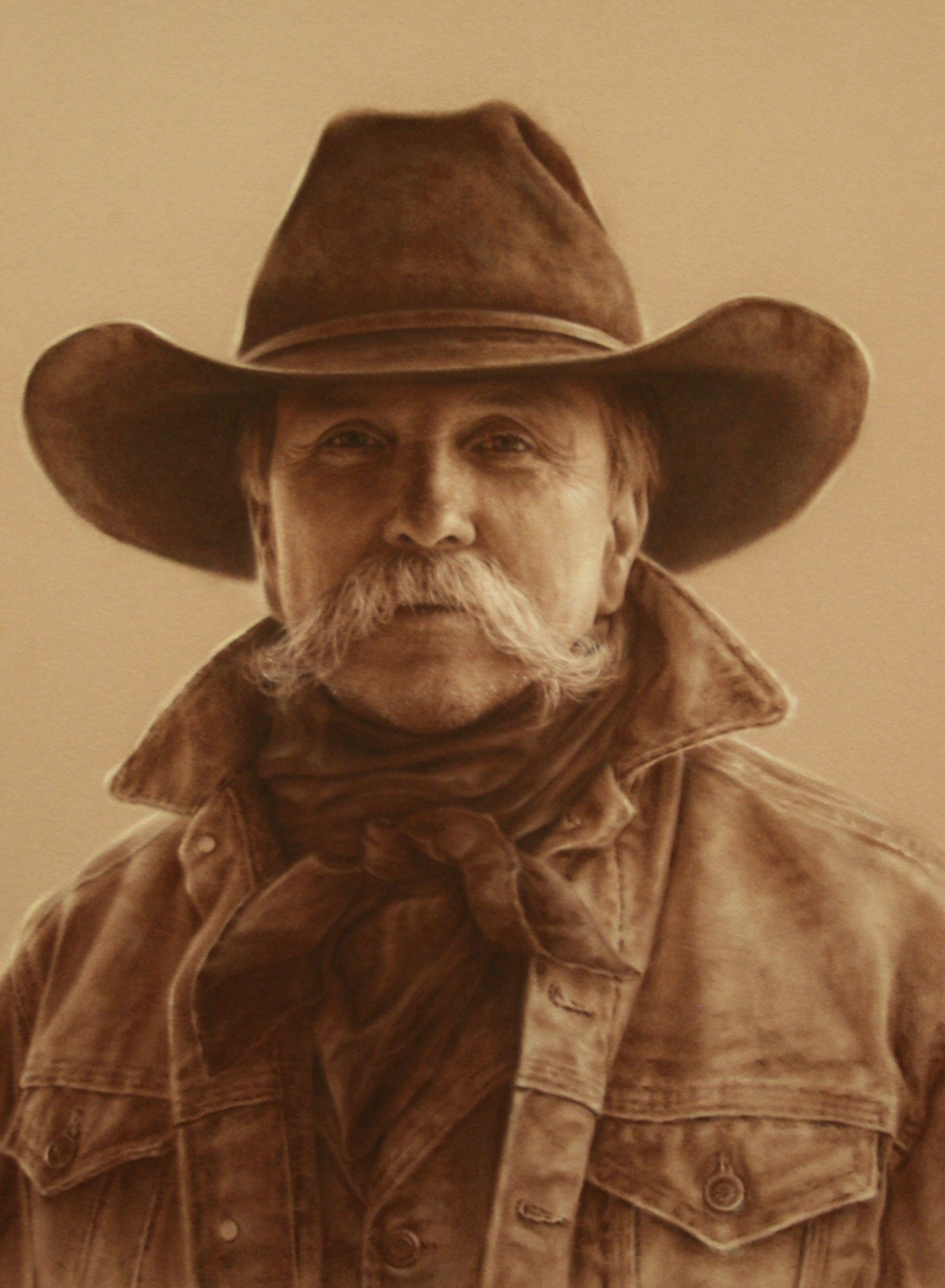

The world-renowned sculptor talks about the importance of Native history, storytelling, and emotion in his bronze renderings.

Somewhere in the collective American imagination lives the essence of the history and legend of the vast American West. For renowned Cowboy Artist John Coleman, that legend lives in bronze.

The Arizona-based sculptor has dedicated his life’s work to reflecting the West in a way that reveals his deep insight into this most significant aspect of our American identity. His dramatic renderings of iconic Western figures combine stunning visual detail with abundant emotional impact, reaching far beyond subtle simplicity to embody this important part of the past in full fidelity — often using only a solitary Native American figure to accomplish the task.

History is a driving force behind much of what Coleman crafts. Consider his ambitious Bodmer-Catlin series, which features 10 figures spanning the Lewis and Clark expedition. The sculptures mirror paintings by 19th-century explorer-artists Karl Bodmer and George Catlin, who retraced the steps of Lewis and Clark some 30 years after the Corps of Discovery and recorded the tribes they met along their journey. The first in Coleman’s series, Addih-Hiddisch, Hidatsa Chief, took best of show at the 39th annual Cowboy Artists of America Sale & Exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum in 2004 and was made part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Coleman’s journey to becoming an award-winning master sculptor began in earnest not when he was young, but in his middle years — a time, he says, when he got back on a path he should have always been on. Sculpting his first work at age 42 and taking up the craft full time in 1994, Coleman quickly developed an avid following. Today his pieces are highly sought-after by collectors and are found in many museums, as well as corporate and private collections, around the world. In 2001 he was inducted into the Cowboy Artists of America; in 2009 he served as president of the esteemed organization; and in 2012 he was named the CAA Artist of Distinction.

C&I caught up with John Coleman at his mountain studio outside of Prescott, Arizona, to talk about his favorite subjects: Western art and history.

Cowboys & Indians: Where did your sculpting journey begin?

John Coleman: Well, for starters, you need to understand that back in school I had some learning issues, ADHD-related, that had me doing so well that by the end of my sophomore year they invited me to leave. As an alternative, we managed a deal where I would be allowed to stay and I could basically take whatever classes I wanted, which turned out to be PE, history, and four periods of art. It wasn’t a path to graduation, but it worked. I found an art teacher who was very good, and, really, that was where this all got started.

I managed to get a job as an illustrator back then, for a hair stylist in California who had a syndicated column. From there I managed to get hired as a technical illustrator at Butler Publications. I was 17. This wasn’t fine art, but it was art — the kind where someone else tells you what to do and you make it. An entirely different thing.

By 19, I got married [to high school sweetheart, Sue] and completely changed gears when we started a construction and real estate business. I blamed practical issues, but I knew it was really more fear that kept me from being what I really should have been. Fortunately, by the time I turned 42, the business had done so well that it allowed me to accumulate enough of a nest egg that I could really do what I wanted at that point. I decided to get back to doing what I was meant to do.

C&I: So for more than 20 years you knew you needed to get back into art?

Coleman: I just wanted to be a part of the art culture. At first I thought I wanted to work at Disney as an illustrator. I hadn’t even considered fine art — a different world — creating and placing pieces in a gallery. The real difference being that creating fine art is more like being a novelist: You are telling a story. You are just telling it in a different way. I didn’t end up going to work for Disney, but I did start making fine art pieces. I saw someone making wall sculptures on TV and thought, I could do that. But I used Native American images. These were still more decorative than fine art. I did my first bronze two years after that.

C&I: How did history influence the direction of your journey?

Coleman: I have always been a history fan. When I think of history I think of the mythology part — what are the life lessons? I used the Native American culture, which is part of the American mythology, though it must still always be told accurately and respectfully. With art, you have to leave room for the viewer’s own story to be integrated into what they are seeing or it falls flat.

Not being a part of the Native American culture, I am really not telling their story, I am telling my story. The core of American culture to me is the Native culture. But I am an American and I am using the Native culture through the lens of history to tell my story. The cowboy and Indian trigger a mood. For example, I made a piece called Lives With Honor that depicts a Native American with all the accouterments of success in his world. It triggers emotion that a man in a business suit never could.

Because of my relationship with other artist-historians who have committed their lifetimes to studying Native American history, such as my good friend and mentor Dave Powell, I have become somewhat of a pseudo-expert on Native American culture myself. People have come to expect it. Every time I had a story I thought would make a good sculpture I would research it in great detail. My idea of being an outsider is very important to me. I have to learn so that I am telling their story respectfully and not violating any of their beliefs or traditions.

C&I: Why did you choose sculpture to tell these stories?

Coleman: What I wanted to say was what was most important. The medium didn’t matter, but sculpture turned out to be the one that worked. I would be just as happy if I had been a writer. But my skill level — my craftsman level — was in sculpture, not words.

C&I: When did you know you had chosen the right path?

Coleman: Shortly after I started out, a collector from Chicago, Howie Alper, called me. A friend had referred him and said he would like my work. He ended up buying my first two original pieces and made a deal with me to buy the first of every piece I made from then on. He has kept that bargain ever since. Howie and his wife, Frankie, have No. 1 of every piece I’ve ever made.

Ten years from the day I started, [the late] Ray Swanson [a Cowboy Artist and past CAA president] called me and wanted to see my studio. I was already in Legacy Gallery [in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Jackson, Wyoming] and gaining respect in the cowboy art world. I got in to the Cowboy Artists of America on my first try. But along with the recognition, I also had to up my game. You have a responsibility to measure up to the other members of the group.

C&I: Did you have any formal training to up your game?

Coleman: I had no formal training, other than my high school art class and a few workshops. I was good mechanically. I am self-taught in sculpture and painting. However mentors are very important to me. Most of the people I admire are the deceased artists — [Paolo] Troubetzkoy, [Rembrandt] Bugatti. They taught me the vocabulary I needed to do sculpture and paint.

C&I: Which of your pieces please you the most?

Coleman: The ones that gave me the most opportunity for growth. The Rainmaker was one of those — my style became more painterly. My growth points were the ones that were most important to me.

C&I: What’s a “typical” day like in your studio?

Coleman: I have a great setup. This is my dream studio. North light with 20-foot windows. I live in the forest. I have rocks and boulders and trees. My studio looks like a lodge with 2,500 square feet of library, sculpture, and painting areas. I work a lot. My best time is in the morning. I usually get in a couple of hours in the morning. I work on multiple pieces. I have to get away from a piece to make sure something isn’t off. As an example, if you are around something that smells bad long enough you will stop realizing it stinks. The same is true with art: If something is off, your eyes will start compensating and you won’t notice something is wrong.

C&I: What would you say to someone who thinks he wants to hang it up in his middle years and become a cowboy artist?

Coleman: Bottom line is that talent doesn’t know age. Most people fear getting older, but the fear of having a lucid moment 10 minutes before I die and recognizing that I might be taking some of my unrealized gifts to the grave is one of the things that motivate me to work harder today. There is always room for improvement. Always, always, always. If you don’t work hard and nurture those gifts you were given, then you only get to be decrepit. If I keep working, in 20 years I will be a lot better than I am today. And that is worth getting old for.

See John Coleman's works at Western Spirit: Scottsdale's Museum of the American West through May 31, 2016, as part of the museum's 50th anniversary tribute to the Cowboy Artists of America, titled A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the Late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West.

From the August/September 2013 issue.