A monograph of one of the most prolific American Indian photographers of his time makes a great holiday gift.

Horace Poolaw (Kiowa, 1906 – 84) once said the reason he took pictures was so that his people could remember themselves. A 2014 monograph of Poolaw’s photography, For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw, shows him as a man of his community and the Kiowa as a people coming to terms with the changes of their times.

Considered one of the most prolific American Indian photographers of his time, Poolaw spent much of his life near his native Mountain View, Oklahoma, shooting portraits and creating a visual record of the vast cultural changes of the mid-20th century. His daughter, Linda Poolaw, describes the transition he captured among the Kiowa as “coming out of the tepee and into the mainstream.”

Poolaw’s perspective was that of an insider, an Indian photographing other Indians. It was a fact he often proudly proclaimed on the reverse of his images: “A Poolaw Photo, Pictures by an Indian, Horace M. Poolaw, Anadarko, Okla.” As the exhibition catalog says, his pictures show “his family and community as they truly lived — as both American and indigenous citizens of the twentieth century.”

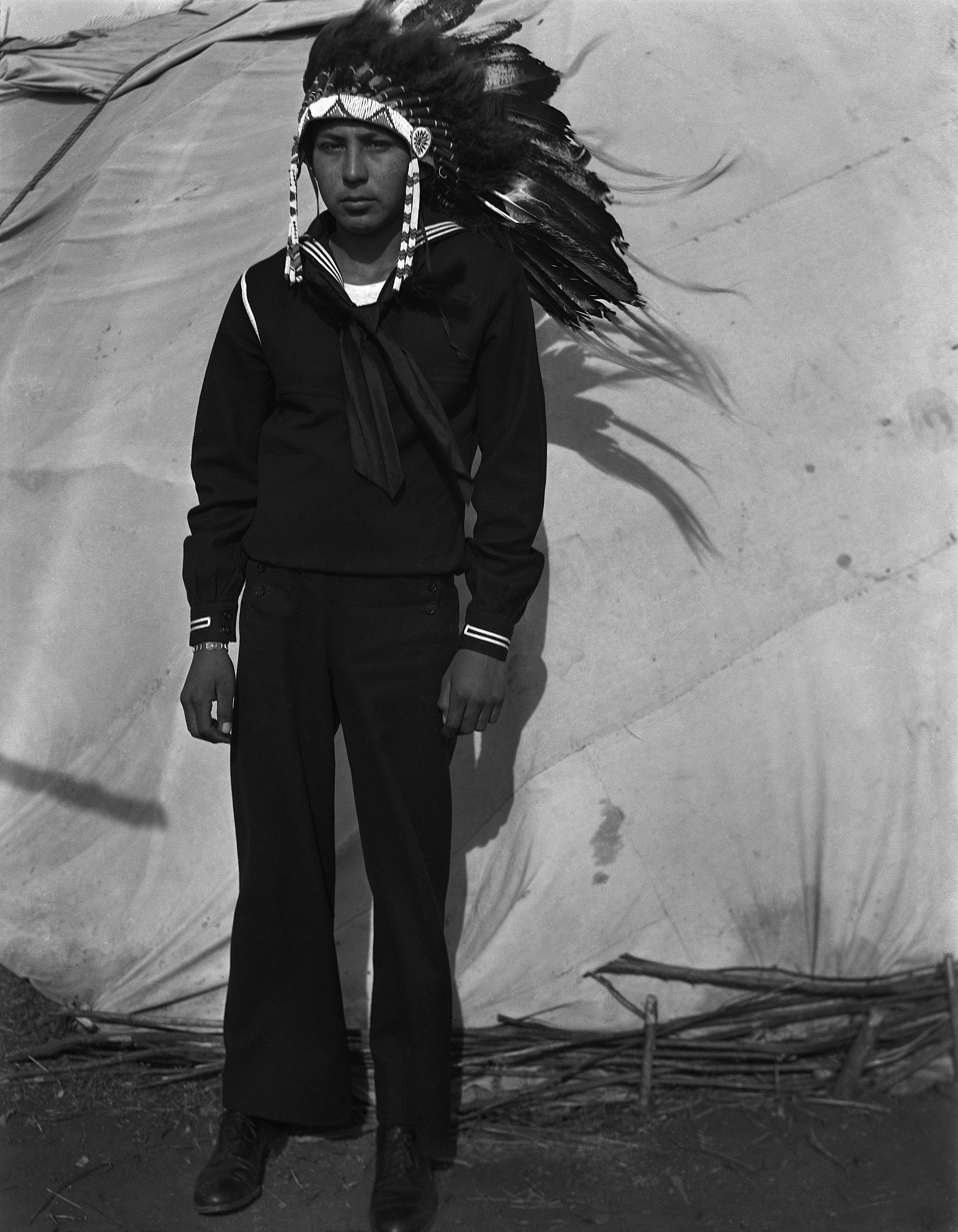

He depicted his subjects with warm familiarity, at funerals, weddings, powwows, and in settings as different as a parade route where Kiowa princesses ride on the hood of a car during the American Indian Exposition in Anadarko and a tarmac where Poolaw (shooting with a timer) poses with his side gunner and fellow tribesman in front of a B-17 Flying Fortress at Fort MacDill Field in Tampa, Florida. One photo shows three Kiowa women wearing short “flapper” hairstyles and heels in the 1930s; another, Poolaw’s eldest son on leave during World War II in his U.S. Navy uniform and an Indian headdress. It’s juxtapositions such as these that can seem incongruous — especially to non-Natives.

“Often American Indians are positioned in opposition to what we think of as American modernity,” says Nancy Marie Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache), chair of American Indian Studies at the Autry National Center. “Horace’s photographs really give evidence of Native people enjoying themselves, occupying those worlds simultaneously.” Instead of merely playing passive roles in American history, they are shown as participants in it. “They hadn’t disappeared. They weren’t starving,” Mithlo says. “They were living productive lives.”

For her part, Linda Poolaw hopes the monograph of her father’s work instills pride in Native Americans and sends a message about their existence: “We were here. And we’re still here.”

From the January 2015 issue.