These seven cowgirls have an extra measure of that special quality we call grit.

They round the barrels at breakneck speed, flying across the dirt for home in a matter of hoof-pounding seconds.

They drive gooseneck horse trailers cross-country, sleeping above the truck bed and showering at truck stops. They muck stalls and toss hay at dawn and dusk, and stay up late with sick foals and their own children. When it’s showtime, they glam it up in crystal-encrusted pearl snap shirts and with hair teased so big it can barely hold a hat.

And then it’s back to the road and the stalls and the next event.

Despite the difficulties, rodeo is a life worth living. But the rewards don’t come easy. To be successful at the sport, it takes a special blend of strength, bravery, and drive. Rising above the talented competition to really make a name for yourself requires something even more. Here are seven cowgirls who have an extra measure of that special quality we call cowgirl grit.

Fallon Taylor

Barrel racer Fallon Taylor is one of the little girls Charmayne James inspired. Taylor first saw the sport on a televised rodeo as a 7-year-old living in Florida. She was hooked.

For her birthday, Taylor’s parents took her to Texas to watch a rodeo, and they never came home.

“My parents are like me: We’re kind of a ‘go big or go home’ family, and so they bought me my permit while we were there on vacation,” Taylor says. “They got me a horse, and I loved it. They’d never seen me so passionate about anything.”

By the age of 9, she had won her first rodeo. At 13, she qualified for her first National Finals Rodeo.

“Going into it I didn’t realize the impact of what it would do to my career just to be a qualifier. I was just like, ‘Hey, what a cool rodeo. I get to go down a tunnel and wear sparkly stuff,” Taylor says with a laugh.

As a teen, she rode out of that tunnel four years in a row. Then the opportunity to try her hand at modeling in New York and acting in Los Angeles took her on an entirely different adventure. She became a model for Axe body spray and appeared in TV shows like Two and a Half Men. But the cowgirl was never far from Texas in her heart, and at 20, she returned to the Lone Star State.

But Taylor almost didn’t return to rodeo. In 2009, she was training a horse when he started to buck. As the horse came down, he hit her face and fractured her skull. When Taylor jumped off, she landed on her head, suffering the same broken neck injury that befell Christopher Reeve in the riding accident that left him completely paralyzed.

Though the injury didn’t leave Taylor paralyzed, it did leave her with trepidation about getting back in the saddle.

“I think injury keeps everyone a little bit more fearful than normal, even the people who think they don’t have any kind of hesitation, so that was something I had to overcome,” she says.

It took a horse named Babyflo, bred and trained by Taylor’s family, to get her back into barrel racing.

“Babyflo is not a horse that is just a tool for us,” Taylor says. “She’s a part of the family.”

When that family member walked away with 2013’s WPRA/AQHA Horse of the Year, it was especially rewarding. Having qualified for the 2013 NFR, Taylor and Babyflo are set to go again in 2014.

The road to NFR takes more than a great horse, of course. It takes a lot of work, Taylor admits.

“You have to be incredibly tough,” she says. “It’s not super-glamorous. You’ll have 14-hour days of driving. You’ve got to basically rebuild your barn for your horses every single time you change locations; that’s probably physically the toughest part. Staying awake, staying fit, staying healthy on the road is a little tough, so we take extra time to cook our meals and try to do the best that we can nutritionally. You have to be able to fight through homesickness; if you can get through that, you can get through it all.”

Staying connected through social media also helps — and it’s a means by which Taylor has found that she can reach out and help others while on the road.

“I was young in rodeo, and I would have just given my right arm to see inside Charmayne’s world one time,” Taylor says. “A morsel of information would’ve been golden to me. So, in this age of social media I feel like it’s a responsibility that we have. I posted a picture of me in the laundromat just to let people know, ‘Hey, it’s not always roses and sunshine.’ We do some things that aren’t so great, but what makes a cowgirl a cowgirl is a lot of tenacity and perseverance.”

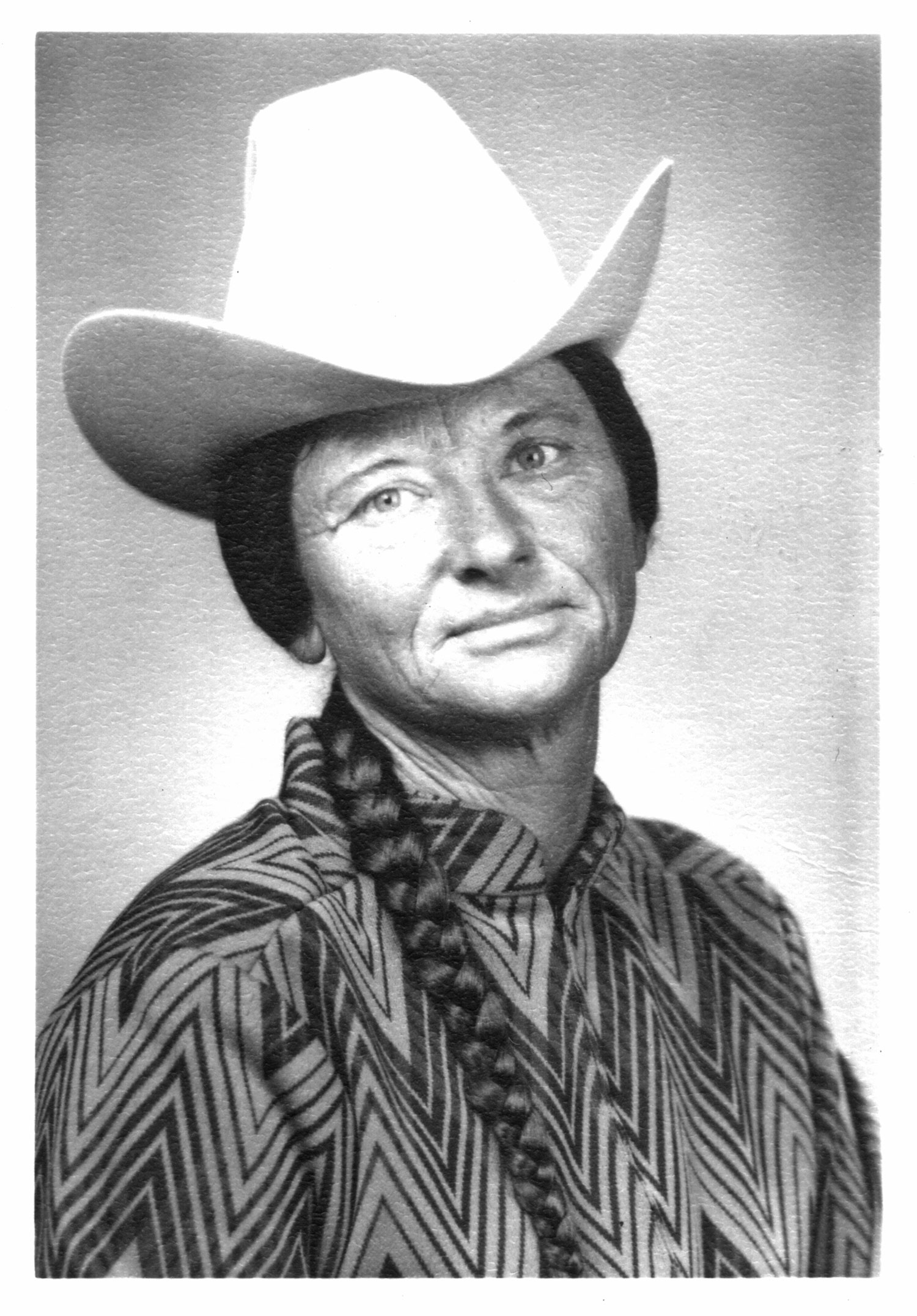

Photography: Courtesy Charmayne James

Charmayne James

Simply put, Charmayne James is the Babe Ruth of barrel racing. She became the first-ever million-dollar professional cowgirl in 1990 and holds the record for the most consecutive women’s NFR qualifications — a whopping 19. With the help of her horse Scamper, she dominated the NFR in barrel racing for a decade, winning an unprecedented 10 consecutive championships from 1984 to 1993, plus another in 2002 on a different horse for good measure.

Despite the fact that she brought women’s rodeo into the money and the spotlight, James admits she didn’t understand the significance of her achievements during her rodeo reign. “Back then, Scamper was such an amazing horse, and it was so effortless for him,” says James, who won her first NFR finals aboard Scamper when she was only 14 — after his bridle broke during one of their runs.

“At the time, I really didn’t have any grasp of the impact, and I think as time goes on it seems to be a bigger feat. Every year it was like, ‘Well, they can’t keep going, they can’t do it another year.’ Everything we did was to prolong his career, but we never had any idea it would be 10 years.”

Growing up in northeast New Mexico, James rode horses every day, helping her family out on their farm and feedlot. The idea to go pro came to her when she was still a young teen, hoping that she might win enough money to buy a truck.

After her main horse broke his leg, Scamper came into her life, and the rest played out like a movie — at least from the public’s point of view. But behind the scenes, it took a lot of hard work to push James to the top.

“I think probably one of the biggest reasons for my success is that I was really driven,” she says. “I rode all the time, learning all I could about how to take care of my horse, how to do a better job. Even from a really young age, that’s kind of how I’ve been. You need to do this — just do it.”

She continues to share that philosophy with many up-and-coming barrel racers through her books and clinics across the country. “You can really make a difference just teaching them the right mechanics,” she says. “When they go out and win, and they change their horses to make them like what they do, that’s real rewarding.”

When she’s not teaching, James spends most of her time at home in Boerne, Texas, raising her two young sons and working with her colts. Although Scamper died in 2012 at age 35, don’t rule out seeing James at elite events in the near future. She came out of retirement to compete in The American rodeo in Arlington, Texas, in March 2014.

Photography: Courtesy Pam Minick

Pam Minick

Legendary cowgirl Pam Minick received her first horse when she was 9 years old, after her mother brought home two palominos from the Las Vegas Strip. The horses had been used to pull a stagecoach up and down the storied avenue to advertise a soon-to-be-built Western-themed casino. When the project fell through and the coach drivers headed home, the horses came to live with Minick and her family — who were ill-prepared for their upkeep.

“We lived out in the desert, but we didn’t even have a corral,” Minick recalls. “She bought these two horses, and all we got with them was the halter.” Despite her mother’s lack of foresight, it wasn’t long before the family built an arena and Minick was old enough to join 4-H. She took up barrel racing and roping, and then, shortly after graduating from high school, she became 1973’s Miss Rodeo America.

After a successful stint as a professional barrel racer — and becoming the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association World Champion Breakaway Calf Roper in 1982 — Minick went on to break barriers in the new business of rodeo television as the first female professional rodeo announcer. She juggled her broadcasting career with her job as director of marketing for the legendary Fort Worth music hall, Billy Bob’s Texas. Working Monday through Thursday at Billy Bob’s, Minick would fly out on Friday and Saturday to host the Professional Bull Riders televised tour.

“The things that I’ve done, much of it nobody had ever done before me, so I didn’t even know that those opportunities were there,” Minick says. “All I did was walk through doors when they cracked open for me. Ignorance is bliss — if you don’t know you can’t do something, you go ahead and try it. I’ve been lucky.”

Although Minick is retired from her full-time work at Billy Bob’s and has given up her 15-year tenure on the board of the WPRA, she’s still as busy as ever, cohosting an RFD-TV show with Kadee Coffman about draft horses, Gentle Giants, and working with a variety of charity organizations.

For Minick, rodeo is about a bigger mission: “It’s a great role model for young girls to see that women can do anything they set their minds to,” she says. “Every time I’m at a rodeo, whether I’m announcing, broadcasting, or at any other event, I always think about who is that little girl who might be inspired.”

Photography: Jill Johnson

Kadee Coffman

When the sideline reporter for the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association walks into a trendy Mexican restaurant in Fort Worth, Texas, dressed in a black silk dress and boots, she looks every bit the stunning rodeo queen. It’s hard to believe Kadee Coffman is running on almost no sleep after driving home through the early morning hours from a rodeo in Oklahoma.

The horse-showing granddaughter of a longtime rancher managed to snag her first rodeo crown with the title of Miss Clovis Rodeo in 2004, before going on to win the prized title at the state’s biggest rodeo, Miss California Rodeo Salinas. But it took a final win in 2007 as Miss Rodeo California for Coffman to realize that, when it came to answering questions for her role as queen, she preferred the other end of the microphone.

“I was like, ‘I want to be the one asking the questions,’ ” Coffman jokes. “But I did really enjoy sharing my passion for the Western industry, so that’s where my drive for being a broadcaster came into play.”

After getting her broadcast journalism degree from San Jose State University, Coffman headed to Fort Worth where she began working as a host for Superior Livestock Auction. She credits her ample camera time there with helping to skyrocket her career.

And then there’s her role model: Pam Minick. “Pam is my everything,” Coffman says. “She was not only my mentor, but she has become a best friend, a confidante, and truthfully like a second mom. She is the Oprah of our industry.”

Like Minick, Coffman set her sights on reporting for the PRCA. But it took her a fair amount of time and patience to achieve her goal. After sending in reels for three years, Coffman finally got a call in 2012 while filming a show in Wyoming with Minick. The PRCA needed a reporter for the Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo, and they wanted Coffman.

“This was 10 days before the event, and so I’m jumping up and down, Pam’s crying, and it was awesome, because I felt all of my hard work had paid off,” Coffman says. By that December, Coffman found herself reporting at NFR.

She hasn’t slowed down since. But Coffman says the long days on the road are worth it for the amazing athletes she gets to meet. “I’m thankful I can help share their story or capture their emotion.”

Photography: Molly Morrow Photography

Mary Walker

It’s been more than three years since Mary Walker’s only child, Reagon, was killed in a car accident at the age of 21, but she still feels his presence everywhere. At her ranch in Ennis, Texas, Reagon’s old horse and a few of his steers spend their retirement.

“He changed my life, and I wouldn’t take it any other way,” Walker says. “But once we lost him, I was like, What do I do? What do I do now?”

You get back up and keep on going, she decided.

But then, shortly after Reagon’s passing, she suffered a catastrophic fall aboard her new horse, Latte. It left her with a broken hip and pelvis, two fractured vertebrae, and two broken toes, which she says were the most painful of all. She was in a wheelchair for nearly four months.

“During those terrible, painful months, I asked myself what I’d done to deserve the worst two tragedies in my life,” Walker says. “My doctor told me I’d recover from my physical injuries, but it was up to me to recover from my emotional ones.”

After attending NFR in 2011 while still in a wheelchair, Walker remembers her husband of 31 years, world champion steer wrestler Byron Walker, telling her she was going to win the world championship the following year. And that’s exactly what she did — on the back of Latte, the 9-year-old gelding who had come into her life just weeks before what was almost a career-ending fall.

“I knew the first time I got on him that he was something special,” Walker says. “And then I asked myself if, at 53, I was really ready to try and make this happen.”

She must have been ready, because in December 2012 Walker became the world champion in barrel racing, achieving the title that had eluded her for so many years. “I remember looking up at the fifth go-around and thinking, It’s almost half over and I’m still at the National Finals,” Walker says. “At the end of the day you can either sit down and quit or go on. And I chose to go on.”

The following year she went on to make reserve world champion.

“It’s been an exciting adventure,” Walker says. “It’s been something you never believe that you’ll ever do.”

Along the way Walker has developed a dedicated following of fellow barrel racers and rodeo contestants who gravitate to her, stopping by her trailer for dinner or to use the shower when theirs is broken.

“I guess maybe we’re the mom and pop of the rodeo, and we really enjoy it,” she says. “We’ve had people at our home all winter long. Why they want to come hang out with us, I don’t know, but we love having them. They’re not kids, but they are to us. We love them.”

Rodeo has helped her heal in other ways, too. “You learn how strong you really are through the day in and day out of rodeoing. You start early in the morning and you don’t quit. It’s not the most beautiful lifestyle in the world because you’re filthy dirty cleaning stalls and feeding horses. You’re not in high heels and lipstick.”

All that hard work is invested for a fleeting moment. “We may drive 1,000 miles for 16 seconds,” she says. “In the end I’ve spent all this money and fuel, and I may win $1,000. I may win $500 and I may win nothing, but we’re out here and we do it because we love it.”

Photography: Mark Reis/The Gazette

Ardith Bruce

Growing up in Missouri in the 1930s and ’40s, Ardith Bruce says the thought of barrel racing never crossed her mind. “I had never even heard of the sport until I got married and moved to Texas in 1949. My husband started me on an ornery ranch horse and took me to some rodeos around the panhandle of Texas and eastern New Mexico. There were a few GRA [Girls Rodeo Association, now the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association] rodeos that had barrel racing in the area, and I competed in several of them.”

The girl was good, and soon she was earning $20, even $30 a weekend at local rodeos. But she had to be quick to adapt — many of the small-town competitions didn’t have standardized barrel patterns.

“The GRA had established the cloverleaf pattern, generally going to the right barrel first, then the left, and on to the third barrel at the end of the arena. However, the committee men who put on some of these small rodeos got rewarded by setting the patterns, so whatever pattern they set that day we had to follow.”

By 1963, Bruce had moved to Fountain, Colorado, where she would become a longtime resident. Today, at the south end of town, there’s a welcome sign that proclaims “Hometown of Ardith Bruce.” It features a black-and-white photo of her racing barrels, commemorating a feat she accomplished shortly after moving there: winning the 1964 world championship on a 14-year-old gelding named Shaw’s Kingwood Snip (better known as Red).

It was a career high, but Bruce remembers it as a difficult year because her husband and young son couldn’t travel with her. “My husband had to keep working to pay for the entry fees and travel expenses,” she recalls. “This was the time that barrel racing began to take off and became a crowd favorite event. It didn’t cost much to put on, and it became almost as popular as bull riding.”

In her 83 years, Bruce has seen and done it all, from hefting mailbags onto trains as a rural Texas postmistress and cooking for sawmill hands to hand-sewing her own ornate cowgirl riding clothes and taking a mistreated, unseasoned ranch horse to the world championship. And to this day she still competes, even when arthritis makes it hard to fling her leg over the saddle.

Photography: National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, Fort Worth, Texas

Wanda Harper Bush

“Judging from tales told and retold, the horsemanship of Wanda Harper Bush should swell to near legendary proportions by century’s end.” So predicted Bill Whitaker in an article he wrote for the Abilene Reporter-News in 1998. He was right on the money, but Bush went one better: One of the most legendary rodeo women of all time, she became the most decorated cowgirl in the history of the GRA and WPRA.

Born in 1931, Bush won her first National Barrel Racing Championship at 21 and won again the next year in 1953. An inductee in the Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame & Western Heritage Museum, Bush has earned 32 world championship titles, including barrel racing, calf roping, cutting horse, flag-racing, ribbon-roping, and all-around champion.

Not bad for card-carrying No. 14 of the Girls Rodeo Association.

“The association was really formed by a group of ranch ladies,” Bush explains. “In the beginning, the association promoted all-girl rodeos. What made it boom was when working women who knew the ranch lifestyle became members and promoted these small regional rodeos.”

It didn’t take long for Bush to start winning the small purses, because she had to. Her earnings on the rodeo circuit went back into the running of her generational family ranch near Mason, Texas. “Back then I worked on the ranch and went to as many riding events as I could handle,” Bush says. “All these little checks would add up to $500 or more a week.”

Bush attributes much of her riding success to her family, especially her dad. “Daddy could ride and make a good horse,” she told the Abilene Reporter-News. “Actually, I think that’s why I’ve been able to accomplish the things I have ... because I know how to ride a horse and what a good horse is supposed to feel like.”

She also knows how to get the most out of her mount. The first horse Bush rodeoed on, oddly named Coon Dog, was a quarter horse who had been blinded in one eye when the slack in a rope came back and hit him. Her father had bought him from an old-time roper, and the young Bush recognized right away that, despite his injury, the horse had ability. She rode “Dog” in her first rodeo — and won.

“I’ve always been able to ride horses and have been lucky to have had several great ones,” Bush says. “When I was just 19 I saw Dee Gee, a bay mare with incredible ability who taught me how to win. My daddy borrowed the money to buy her. He was a great coach and made me feel I could do anything. My brother trained these ranch horses so that I could ride and win riding them.”

Asked about her two back-to-back championships riding Dee Gee, Bush modestly replies, “I just did what I did, and I discovered I could ride as good as anyone else could.”

From the November/December 2014 issue.