Chippewa painter David Bradley has always taken his responsibilities as a Native American artist seriously.

When David Bradley got his start more than 30 years ago, he came out swinging — politically and artistically. As an artist-activist, he has taken on art fraud, stereotypes, art history icons, pop culture, and cultural appropriation. Nearing the end of his controversial and important career, he’s still doing battle, but a very different kind.

“I was diagnosed with ALS [Lou Gehrig’s disease] during Indian Market week, in August 2011, three years, eight months ago,” Bradley says. “The median survival time after diagnosis is three years, three months, but I have seen friends die in much shorter time and others are surviving much longer.”

Even before this latest chapter for the 61-year-old Bradley, it’s been a life’s journey of determination. “To be an artist from the Indian world carries with it certain responsibilities,” he’s frequently quoted as having said. “We have an opportunity to promote Indian truths and at the same time help dispel the myths and stereotypes that are projected upon us. I consider myself an at-large representative and advocate of the Chippewa people and American Indians in general. It is a responsibility which I do not take lightly.”

He still stands by — and for — those words.

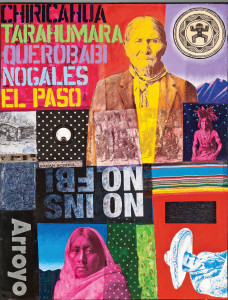

In spite of his deteriorating health and because he can no longer conduct a spoken interview, Bradley talked with Cowboys & Indians by email from his longtime home, a small adobe he built himself on the Turquoise Trail, about 15 minutes south of Santa Fe. The outspoken artist shared his thoughts on the current exhibition of his work at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, Indian Country: The Art of David Bradley, which features 40 works of art spanning his métier, including acrylic paintings, mixed-media works, and bronze sculptures. He looked back at his heritage and his hard-fought career. And he looked forward to the hard-won legacy he hopes to leave.

Cowboys & Indians: In the David Bradley Wikipedia entry, there’s one quote from you: “When I first entered the somewhat glamorous world of professional art, I thought I would steer clear of politics and keep my life as simple and positive as possible. Eventually, I realized that Indians are, by definition, political beings ... I saw the continual exploitation of the Indian art community by museums in the Southwest ... I witnessed multimillion dollar fraud by pseudo-Indian artists ... and so [I] began to speak out on what I saw as widespread corruption in the art world.” Still feel that way?

David Bradley: I hadn’t seen any Wikipedia info about me, but that is an old quote. I’m not sure how accurate it is, but I would delete the “by museums” part because, while some of the exploitation of Indians was done by certain museums, much more was done by unscrupulous galleries and individuals. To finish off that Wikipedia quote, I would add: “Little did I know what kind of hornet’s nest I was stirring up and how I would be punished the rest of my career for what I thought were good and noble deeds.”

From day one I had put my career on the line for this cause. When the ongoing battles really got vicious, our grass roots organization melted away and I was left swinging in the wind. I became the target for most of the backlash, slander, and disinformation campaigns. A couple people even said that they and their supporters would ruin my art career. I became the most blacklisted Indian artist in the country, and it continues to this day. But I know we did the right thing. We started a national dialogue about Indian identity, which resulted in the passage of both a New Mexico Indian Arts and Crafts Law as well as a federal version of that law.

When we first created the grass roots Indian organization, we held public meetings on the subject and got the signatures and support of 600 Indian artists at the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Arts and Crafts Fair. Indian artists were getting tired of well-known frauds claiming to be Indian so they could take opportunities that were set aside for Indian people. But our efforts were also aimed at the multimillion-dollar counterfeit “Indian” jewelry being mass produced by non-Indians abroad and sold in this country as authentic Indian arts and crafts. I think it was the only time that a grass roots group of Indians organized themselves in this way and went up against great commercial and political powers in an effort to stop this kind of exploitation of the Indian community. Our motivation was simple: As Indian people, we’ve had everything stolen from us — our land, our resources, etc. Now that our very identity has become a marketable commodity, we won’t let them take that as well.

C&I: What’s it like to be far from your traditional (watery) tribal lands and living in (dry) pueblo country?

Bradley: I was born in California when my father had a temporary job there, but my family moved back to Minneapolis when I was a few months old. I grew up in Minnesota. I used to return almost every year, but now that my parents and a sister have passed away, I haven’t gotten back there much. I love and sometimes miss the lakes and woodlands, but I also love the desert and mountains.

I still occasionally do pieces about my Chippewa homeland and I always will, but most of the time I paint my day-to-day experiences and those take place here and now. Back when I was an art student at IAIA [Institute of American Indian Arts], I lived on the Navajo rez off and on for a couple years. Now my wife and son are members of Jemez Pueblo [in New Mexico], and I am a fluent Spanish speaker with the experience of living south of the border. I have always felt very much at home in the Southwest. When I first moved to Santa Fe, I told a friend that I think I will live and die in Santa Fe.

C&I: Other places have been important in formulating your outlook and your art. Tell us about your life-changing “experience with essentials” in the Peace Corps.

Bradley: The Peace Corps slogan was “The toughest job you’ll ever love,” and that turned out to be true. I went to Peace Corps training in Costa Rica, which was a paradise in 1975. I spent about a year working in the Dominican Republic, in an agricultural program on the Haitian border. It was OK — I truly liked helping people and feeling like I could make a difference, but I really wanted to work with Indian people. So when a rare opportunity arose to work in a livestock program in the highlands of Guatemala, I jumped at the chance.

In both countries, I was in the toughest programs of the Peace Corps. I had Peace Corps friends who lived in a big city, ate at fancy restaurants, went to discos at night, and lived in a modern apartment. In my two programs, I lived in a thatched-roof hut with a dirt floor, in the mountains, far from civilization, with no electricity or running water, and sleeping in a sleeping bag. Needless to say, my programs had a very high rate of attrition; I was one of the very few who lasted the full term.

The experience taught me a lot. I got to look at our country and our American way of living from the point of view of utterly poor Third World countries. It also gave me an independence and resiliency. I could pretty much travel anywhere in this hemisphere, survive, and blend in. I guess it made me braver — it made me believe in myself. I later believed I could be an artist and survive, and so I did.

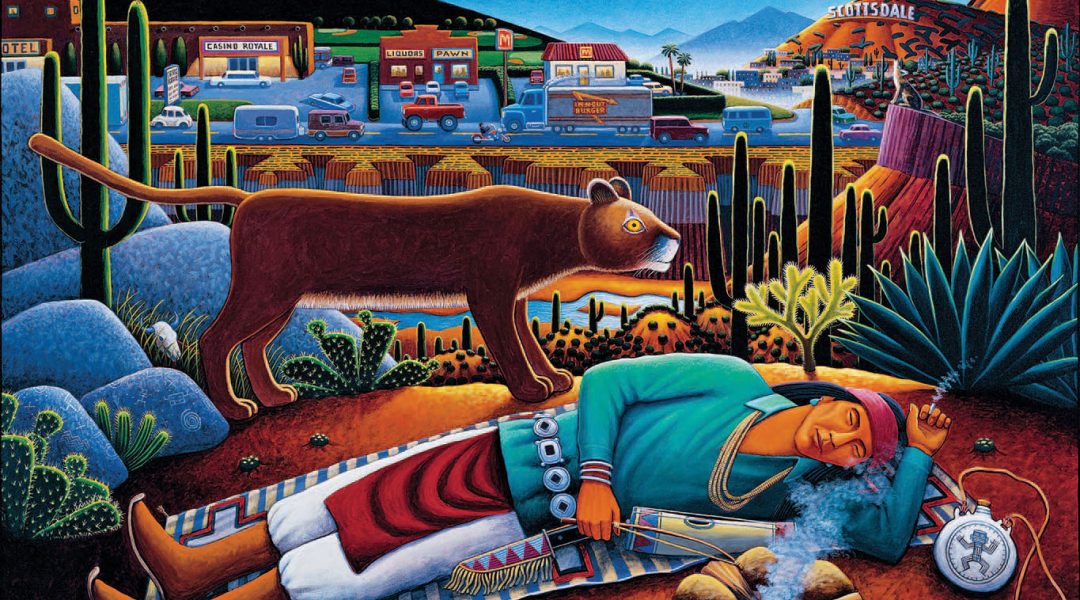

C&I: You frequently use iconic images like the Mona Lisa and American Gothic as springboards for social commentary. In a different vein, your “folk narrative” panoramas have so much going on that the viewer could spend a long time looking for meaning and people they might recognize — almost like the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album. You also do mixed media pieces and bronze sculpture. What inspires all these different styles?

Bradley: I am mostly known as a painter, but my IAIA degree was in sculpture, 3-D. In the early 1980s I won the best of painting award at the Santa Fe Indian Market, and a couple years later, I won the best of sculpture award, which irritated several of the sculptors.

I have always greatly admired artists like Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Picasso, who had a command of various media. Not many artists can sculpt as well as paint. I have dabbled in jewelry, printmaking, and photography, as well. I have always had a great desire to be a professional musician. Until ALS took away my motor control, I played saxophone, guitar, and a little violin and keyboard. I haven’t done all these things to impress anyone else but myself. I just truly enjoy finding various ways of expressing the creative force.

C&I: What is your current focus?

Bradley: These days, with declining health, I pretty much have my hands full dealing with ALS. To some degree, I am tying up loose ends in my life, loving my family, trying to be the best dad and husband I can be, loving life, and working on my legacy. I have been so fortunate to be given this Indian Country exhibit at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, and all the publicity that goes with it, especially the beautiful 135-page full-color book that goes with the exhibit. Thank you, MIAC director Della Warrior, curator Valerie Verzuh, and the whole MIAC community. Thank you, Dr. Suzan Harjo, who wrote a beautiful essay in the exhibit book. And a special thanks to my wife, Arlene, and son, Diego.

C&I: What do you hope people will take away from the exhibition — and your life’s work?

Bradley: They say that artists seek immortality through their artwork. I guess that we all hope that one day, 100 years from now, our artwork will be deemed relevant and meaningful to the average person. My favorite quote that I may have coined is “To be an artist is to seek Truth.” When you go see my exhibit, the truth is in the narratives. It is in the way I used my heart, brain, and hands to create the work, and, hopefully, in the way I lived my life.

Indian Country: The Art of David Bradley runs through January 16, 2016, at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe.

From the August/September 2015 issue.