The lucky man with the magnificent mustache talks about a fortunate life of telling stories, riding horses, and being a Westerner.

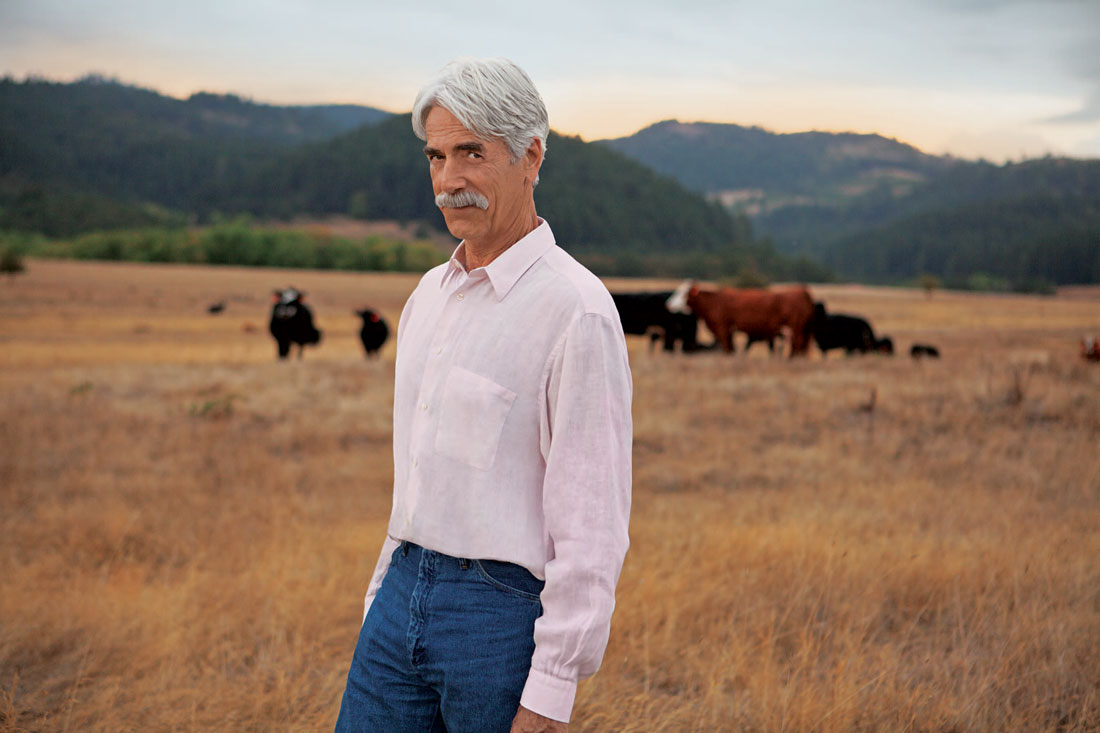

These days Sam Elliott has one foot in Oregon, where, as he describes it, he has “a couple of hundred acres of grassland and oak savannah in the foothills of the Willamette Valley — a rich piece of ground with a lot of wildlife.” His family moved to Portland from California when he was a kid. “After school I went back to California to pursue my career,” he says. “My mom and dad both died in Oregon. My sister, Glenda, and I still have the family home in Portland. Oregon always feels like home.”

Throughout much of the year, he and his wife, actress Katharine Ross, live in Malibu, California, on “another beautiful piece of ground.” They’ve lived there since they met in 1978. Their daughter, Cleo, lives nearby, and “as all of us are natives, the California roots run deep,” Elliott says. “It’s a nice balance, and we’re very fortunate to have these places.”

On this particular weekend afternoon, Elliott is settling in after the “long haul” up Interstate 5 with the traveling circus of family cats and dogs to talk about his life and a show business career that spans back to his first big-screen appearance in 1969, as a bit player in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. At 69, the Sacramento-born actor has a résumé to be proud of that lists a wide variety of roles in an impressive diversity of film and television projects.

Cowboys & Indians readers may remember him most fondly for a passel of terrific made-for-TV westerns from the 1980s and ’90s — a period when it often seemed like he and friend Tom Selleck were the only folks in Hollywood eager to keep the genre alive — but Elliott has also excelled in contemporary dramas and comedies, playing everything from a blunt-spoken presidential advisor in Rod Lurie’s The Contender (2000) to a Marlboro Man type dying of lung cancer in Jason Reitman’s Thank You for Smoking (2005).

And while he’s willing to wax nostalgic while discussing such western fan favorites as Tombstone, the epic 1993 drama in which he plays Virgil Earp opposite Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp, Elliott seems slightly more eager to emphasize how fortunate he’s been to have the career he’s had and the fact that he still gets a job once in a while.

“Yeah,” he casually mentions, “I just did a guest spot on Parks and Recreation. Can you see that? Eagleton Ron was the character’s name, and it was a hoot. It was great being on a set and having a few laughs with a bunch of very smart people. Funny’s good. We could all stand a few more laughs these days.”

To paraphrase his famous line from The Big Lebowski — obviously, this dude continues to abide.

Cowboys & Indians: What has given you the most satisfaction as an actor, or put another way, why do you love your profession?

Sam Elliott: Because on some level it’s what I’ve always wanted to do. And I think that anybody who makes a living off some passion that they were bit by early on in life is very, very fortunate. I love this business — this art of telling stories, of entertaining people. It’s a wonderful thing. And if you can inspire somebody along the way, without getting too political, maybe it can do somebody some good. It’s all about entertainment and taking a ride once in a while.

C&I: Speaking of riding, you’ve spent quite a bit of time on horseback in your movies.

Elliott: Well, being around horses is another wonderful thing. I got much closer to horses after I got into the movie business — out of necessity. I was never much for trail rides and that kind of stuff. So I spent a lot of time in pens and arenas before I’d start on a job. I got on a lot of different stock instead of just getting comfortable on one horse. There were a lot of good horses, some not so good, and I got a lot of help from a few good friends. R.L. Tolbert, Corky and Pinky Randall, to name just a few

C&I: What have been some of your most memorable experiences in the saddle?

Elliott: The most memorable are the most embarrassing, so I’ll keep those to myself. I did some dressage once in Wild Times, a miniseries. Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. were in it. And Tim Scott. They’re all gone now. Anyway, I rode this dancing horse named Mister, owned and trained by Pinky Randall. That was a real treat. And there have been other times — like pushing a herd of horses in Conagher, a movie I did with Katharine. Or loping around on a flat saddle in Gettysburg. Any of those parts that required some iota of horsemanship always got my attention and made me work harder. If you’re going to get on a horse, you want to look good on one. There are too many people out there who know the difference.

C&I: Of course, a lot of actors are all too willing to, ahem, exaggerate the extent of their expertise. You can go as far back as the very first silent western, The Great Train Robbery, and if you look closely at one scene, you’ll see one of the outlaws has an awful hard time getting on his horse.

Elliott: [Laughs.] You always want the part. And they know you want the part. There was a director named Bob Totten, who directed Louis L’Amour’s The Sacketts. Before we started shooting, Totten got me and Tom [Selleck] and Jeff Osterhage into an arena. He had us catch our horses, saddle them up, ride around a little bit, get off, unsaddle them, and get the hell out. Totten knew some actors would say anything to get a part. Anyway, we all got there. And what a time it was. Louis L’Amour, Ben Johnson, Slim Pickens, Jack Elam, Glenn Ford, Gilbert Roland, Ruth Roman — we were lucky to be there.

C&I: It’s safe to say that most people tend to think of you as a cowboy — or, if you prefer, a Westerner. What does that mean to you? How would you define what it means to be a cowboy?

Elliott: It’s a set of values that you’re introduced to or you adopt during your lifetime. In my case, my folks all came from the Southwest. My mom and dad both grew up in El Paso, Texas, and there were a couple of generations before them in Texas. Somebody fought at the Battle of San Jacinto, somebody was killed by Indians, and somebody got shot off his horse after coming out of a bar in Giddings, Texas. It’s a heritage that I’ve always been proud of and something I was aware of early on.

And I saw a lot of westerns when I was a kid at the Saturday matinee back when I got hooked on wanting to be an actor.

It’s just a way of thinking. And it’s certainly a way of living.

C&I: What westerns were your favorites while you were growing up?

Elliott: I had a lot of favorites. I grew up in a time when the western was big business — on film and on television. And I saw a lot of it. There’s a simplicity about the western and there’s the struggle — man against man, man against nature, man against himself. All of it played out against the land. That’s always been fascinating to me.

C&I: How do you think you might have fared in the Wild West? Do you think you might have survived and thrived as a real cowboy?

Elliott: I’d like to think I could have. Seems to me you just had to be tough and have some common sense and a will to survive. I’ve spent a certain amount of my lifetime surviving on some levels, just getting by, and being out in nature. I was very fortunate that I was introduced to that at an early age. My dad, who was an Eagle Scout, worked for the Fish and Wildlife Service until he died at 54. He started trapping gophers and killing coyotes in Marfa, Texas, and he wound up with all the western states under his jurisdiction as a regional supervisor for predator and rodent control with the U.S. Department of the Interior. We did a lot of camping and a lot of fishing back in the day.

C&I: So you grew up connected to the land and to the outdoors. After Texas came California, and then Oregon. Do you keep any cattle on your spread there in Oregon?

Elliott: Playing a cowboy a few times in my life doesn’t qualify me to be a cattle grower — that’s a life’s work.

One of the blessings that came with this place in Oregon is our friends and neighbors. One in particular, a man named Lynn Kampfer, runs an outfit that surrounds our place. The Diamond K covers 4 square miles and it’s the real deal and produces some of the best grass-fed beef in the country. Lynn runs some of his cattle on our ground. So in that sense, I am in the cattle business.

Stewardship is our main goal. For the water. For the land and what lives upon it. We never overcrowd or concentrate the cattle in small areas. No overgrazing. Pasture rotation breaks the cycle of parasites — worms, ticks, and fleas. These cattle are raised the old-fashioned way. They are free to range, roam the hills. No growth hormones or antibiotics are used. If an animal gets sick, we treat ’em, with a prescribed treatment, of course. The cows are Herefords; the bulls are Angus. It’s a beautiful operation and I’m lucky to be part of it.

C&I: Back to the movies. Last year you made The Company You Keep, a movie directed by and starring Robert Redford. It was the first time you had worked together since Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Elliott: Redford worked ... I watched. I don’t think he even knew that I was in Butch Cassidy until I told him. I sat across the table from him in a card game, Card Player No. 2. I’m literally a shadow on the wall. The only reason my name is in the credits is I was under contract to 20th Century Fox at the time, the studio that made the movie.

C&I: You have been fortunate to work with so many other notables over the years, from folks like Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. to Patrick Swayze and Jeff Bridges.

Elliott: One of the great perks of the movie business is that you get around and you get to be around some very interesting and talented people. On all sides of the camera. The first movie I starred in was a western called Cactus [released as Molly and Lawless John] with Vera Miles. We shot in Santa Fe; we did some interiors at Studio Center in the San Fernando Valley. One day John Ford showed up — he was there to visit Vera. John Ford! That stopped the show for a while. It might as well have been the pope. I’ve felt that way about a lot of people I’ve worked with over the years.

C&I: You and Patrick Swayze worked together in Road House, a movie about professional bouncers that played almost like a modern-day western. What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when someone mentions Patrick Swayze?

Elliott: My mijo. It makes me sad. Patrick had it all. He was a real specimen ... and he was a gentleman. He had a great career and a lovely wife. That should have been a long road.

C&I: You served as a cowboy storyteller in The Big Lebowksi, the comedy you made with Jeff Bridges for Joel and Ethan Coen. Are you surprised by the size of the cult following that movie has generated? The fans actually have Big Lebowski conventions from time to time.

Elliott: There are a number of them across the country, if I’m not mistaken. They have one up in Portland, where everyone gets sloshed on White Russians, and then they take a walk down some boulevard in their bathrobes to sit through a midnight screening of the movie. That’s very Portland. I think it’s well past the “cult” following. People love that movie. The Coen brothers are clearly geniuses — they make great movies. They made a hell of a western [with True Grit]. As a matter of fact, I think The Dude was in that one, too.

C&I: Outside of westerns, I would venture to say your most enduringly popular performance has been your portrayal of the title character in 1976’s Lifeguard.

Elliott: I used to run into girls that would say, “God, I loved you in Lifeguard.” And now they say, “God, my mom just loved you in Lifeguard.”

That’s a movie I had to do. I was right for it and I knew it. I was living on the beach at the time. I was in the ocean every day. I’d been a lifeguard when I was a kid. In chlorinated water, I admit, but still a lifeguard. And both of my parents had been lifeguards in Washington Park in El Paso. It’s where they met.

But I couldn’t get a meeting on it. I found out later that the agency I was with was touting another client for the part. And then a lucky thing happened. Dan Petrie, the director, was at home brushing his teeth and getting ready to go to bed. His wife, Dorothea, was already in bed with the TV on. She was watching a movie called Frogs. It had just started and she sees me in the beginning of the movie and says, “Danny! Come and look at this guy.” So he came out and they watched Frogs and got my name off the closing credits. The next day I got my meeting. And I knew when I left it that I had the part.

C&I: What was the best piece of advice you got when you started your acting career? Was it something you heard from one of the screen legends you worked with?

Elliott: I worked with Jimmy Stewart one time, late in his career, on a TV show called Hawkins. Stewart was a defense attorney and I was the young DA. It was August and we were shooting on a soundstage at the old MGM lot in Culver City [California]. It was hot as hell. For a week I watched Stewart’s stand-in help him into his suit coat then a topcoat just to do his lines off-camera. It wasn’t anything that was said, but that vision of Jimmy Stewart stuck with me, and I’ve sweated through a lot of scenes off-camera ever since.

My mom, who was a schoolteacher among other things, was my greatest supporter. She mentored me and encouraged me until the day she died.

My dad had a few gems he offered me over the years. One was, always do more than is expected of you. That served me well. The other was a little more to the point for this man from El Paso who could not fathom why his son would want to pursue a career in the movie business. “You’ve got a snowball’s chance in hell of having a career in that town.”

I used to think of that in a negative sort of way. But on some level that was the best piece of advice that anyone ever gave me. Because I knew this was something to reckon with. It wasn’t going to be easy. It wasn’t something that was going to be handed to me just because I wanted it. It was something I was going to have to work hard for. And I did.

I like to think I’ve given something back to this business and to the fans with the choices I’ve made, the work I’ve done. It sure has been good to me. And it ain’t over yet. ... I’m a lucky man.

From the November/December 2013 issue.