After whiskey smuggling, gold prospecting, cattle trading, and heavyweight boxing, the author of Jim Kane has one final goal: to put together one more ranch.

He’s a fifth-generation Arizona cowboy and rancher, but now at the age of 81 he has no land or cattle to his name. It gives him a nagging, goading sense of disappointment, and the fact that he’s written 14 books and won two lifetime achievement awards for his contributions to Southwestern literature doesn’t begin to make up for it.

“I never wanted to be a writer,” says J.P.S. Brown, sipping a lunchtime beer in his front room in Patagonia, Arizona. “All I ever wanted was to get back on a ranch like the one where I was raised, but it just didn’t work out for me. I took too many chances. I trusted people I shouldn’t have trusted. I had four ranches and I lost every one of them. In the meantime this writing had got a hold of me, and I couldn’t find a way to quit it.”

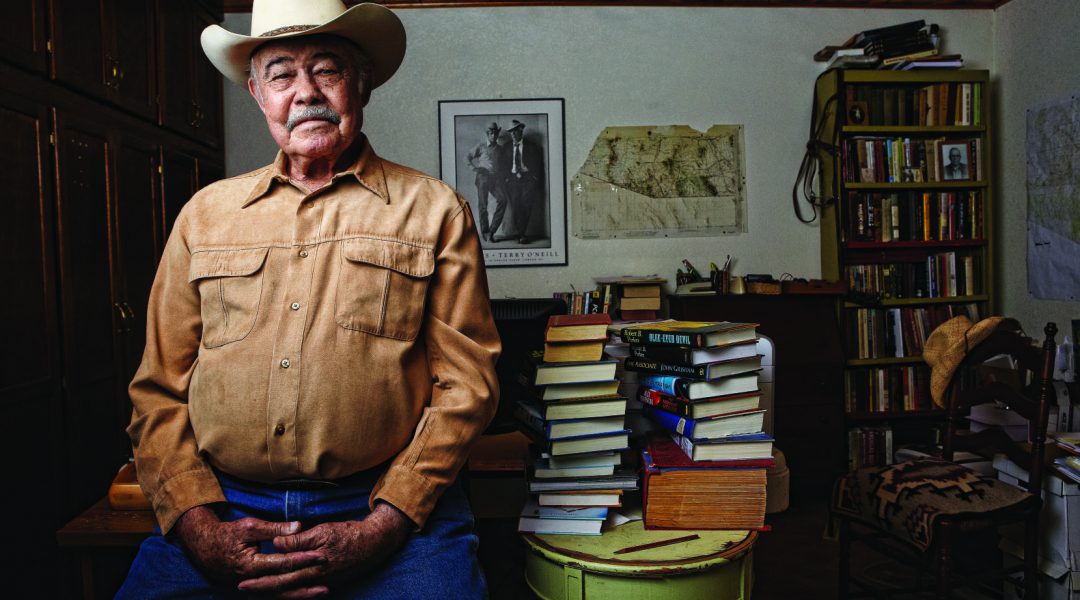

Moving into his ninth decade now, with seven heart attacks and five marriages behind him, Joe Brown is still a big, imposing, forceful man. His laughter lights up a room and his occasional flashes of anger, funneled through small, smoky green eyes, seem to scorch the walls. Refueling himself periodically with coffee, beer, and pinto beans from a saucepan on the stove, he talks for six hours straight about the big, adventurous, extraordinary life he has lived.

First and foremost, he has always been a cowboy and a cattleman, but as a young man he was also a formidable heavyweight boxer. He sparred once with Rocky Marciano and fought professionally in Mexico. He spent four years on active duty in the U.S. Marine Corps, traveling to Japan and Korea, and came out vowing to wear a cowboy hat and boots every day for the rest of his life. In between ranch work and stints of cattle trading, he has worked as an alpine rescue instructor, a whiskey smuggler, a gold prospector, a stuntman, and a movie wrangler — and he’s one of those rare men of action who also has the talent, patience, and discipline to sit down and turn his experiences into literature.

“Writing has always been easy for me,” he says. “In high school, on the bus back from football games, I would write everyone’s compositions for them. At Notre Dame I was a journalism major and I breezed through that while working 40 hours a week at an ironworks and doing a lot of boxing. I started writing fiction in the summer of 1964 when I was laid up with hepatitis and I got hooked on it. I can’t say I really enjoy it, but I’ve been writing every day since.”

His first novel, Jim Kane, was a thinly fictionalized account of his experiences buying and driving cattle out of the Sierra Madre mountains of northern Mexico in the 1960s. Written in clean, true-ringing prose — like Hemingway with a cowboy sensibility — it was published in 1970 to widespread acclaim. Brown was prospecting for gold in the Sierra Madre at the time, but a pump broke on his sluicing machine, and he came back up to Arizona to discover that he was urgently required in New York City to speak at the Harvard Club and appear on nationwide television. He was a new thing on the cultural landscape: a genuine ranch-bred cowboy with genuine literary talent.

He sold the movie rights and Jim Kane was made into the disappointing Pocket Money with Paul Newman and Lee Marvin. Brown, who blames the producers and director for screwing up his story, became good friends with both actors, and they spent many evenings together drinking beer and telling stories. Whenever Marvin was asked about Brown he would always say, “That’s the wildest son-of-a-bitch that ever walked.”

In the town of Navojoa, Sonora, people still tell stories about the time Joe Brown buzzed the roof of the whorehouse in his plane and knocked off the madam’s TV antenna. “I was a hedonist in those days,” says Brown. “I loved music, whores, drinking, and dancing. I took a lot of risks and I really had a good time.” One of his bar amusements was to take a bite out of a beer glass, chew it up, and swallow it. “There’s no secret to it,” he says, “You just have to chew it up real good.”

Brown’s second novel, The Outfit, was based on his work as a cowboy on Art Linkletter’s million-acre unfenced ranch in Nevada, and it was more popular with working cowboys than New York critics. He wrote his third and greatest novel, The Forests of the Night, while working on a ranch high in the Sierra Madre, and he nearly lost the manuscript when he came downhill to celebrate its completion. It’s the story of a jaguar that starts hunting people, and a Mexican rancher who starts hunting the jaguar. The book has a hallowed cult status among writers and academics in the Southwest, and the Arizona-based author and journalist Charles Bowden calls it “the finest novel ever written in our region.” Last year it became the first of Brown’s books to be published in France.

“Don’t think I don’t appreciate it when someone says my stuff is good literature,” he says. “I work damn hard on my words, and I really care about the subject matter of my books, which is cowboys as they are. I’ve never read or seen anything else that accurately portrays a cowboy’s work. It’s always about his saloon shootings or whatnot, but there’s just as much drama and humor in what a cowboy does in his daily work, with no background music, no audience, and no ticket sales.”

Brown displayed his deep knowledge of horses and horsemanship in Steeldust, which is partially written from a horse’s point of view. Then he delved into his family history for a set of four western adventures called The Arizona Saga. When his forefathers came into this part of southern Arizona, it was still Mexico and there were Apaches to deal with. “The Apaches were opportunistic predators and you always kept a close eye out for them,” he says. “The Mexicans were wonderful. We were immigrants here, and they sold us land and helped us stock it, and welcomed us with splendid hospitality. The ranch culture here is still completely bilingual and bicultural. We’ve always felt more akin to Sonorans than northern Arizonans.”

From the February/March 2012 issue.