The lone woman in what was then an all-male sport, bull rider Jonnie Jonckowski held on hard with the fire in her belly and the thought in her head: "Everyone's gonna know who the hell I am."

Jonnie Jonckowski.

It’s a name every sports fan should know. Yet, when asked today, most would respond, “Who’s he?”

First, he is a she. Those on the road with Jonnie more than 30 years ago hitting bull riding jackpots and rodeo invitationals and anywhere else offering a chance to earn a few bucks hanging onto bucking animals who don’t recognize personal pronouns will surely attest to that.

Jonnie Jonckowski. The name is bigger than rodeo. Or at least it should be.

Jonnie Jonckowski was the first woman to compete against men at the top level in professional bull riding, riding in the men’s bull riding World Championship at the Justin World Bull Riding Championship in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1992. She was invited among an international contingent, considered one of the world’s top 30 bull riders.

Before competing in the world’s most dangerous organized sport, Jonckowski had been an accomplished track and field athlete. She was born in Fargo, North Dakota, in July 1954, so much as she burst into the world revving to make a mark. Early on she was an incorrigible tomboy withering to no challenge. She wanted to be first, the best, the highest, the strongest. The rougher the horseplay, the better. Jonnie’s mom made her wear jeans because she kept tearing up her dresses.

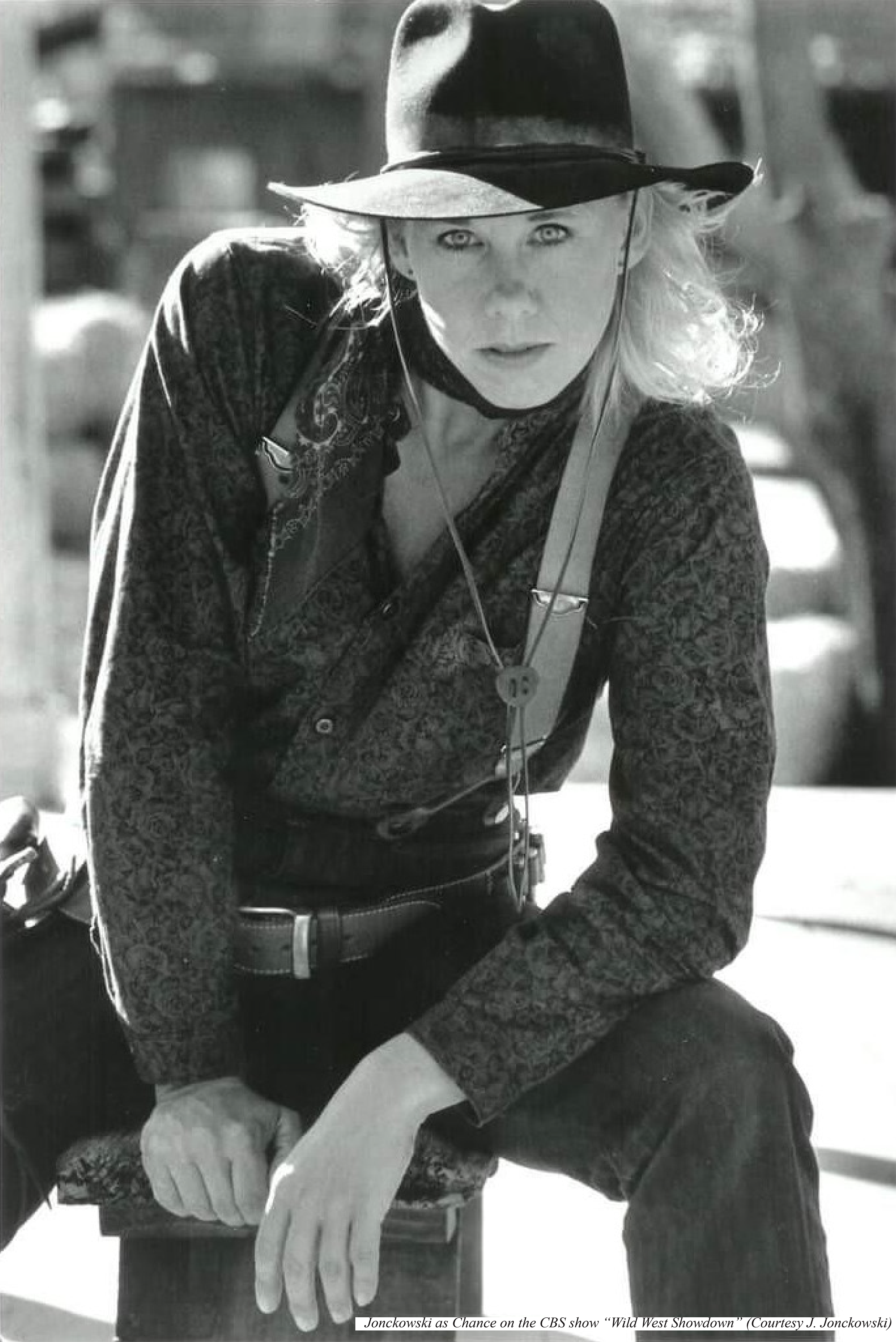

This is me in character on the set of a TV show called Wild West Showdown. I was in my late 40s then. I played an outlaw named Chance — a back-shooting, cattle-rustling, horse-stealing, bank-robbin' son of a gun. During the year the show lasted, I could do all the stunts: fall out of buildings, have bar fights, jump on a horse and ride through the middle of town. I lived that look look and never wanted to take that hat and red shirt off. The fictional town was called Broken Neck. The location was in Placerita Canyon, California, where lots of westerns were filmed. The first time I rode down the street, I got shot full of holes and fell off my horse and onto the dirt. It was the coolest thing!

Rambunctious little Jonnie didn’t stay small. In high school, she shot up 9 inches to a lanky 5 foot 8 and began winning track and field events. With “the Olympics on my brain,” she was second in the country running for Flathead Valley Community College (a small school in Kalispell, Montana) and was headed for the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal. In the final qualifying event for the pentathlon, however, she clipped a hurdle and went sprawling. A severe back injury crushed her dream.

She left college. For two years, she could barely walk. She was lost and despondent. One afternoon at a restaurant outside Billings, she saw a sign advertising an all-girls rodeo. No longer able to run like the wind, she figured she could sit on an animal doing the work.

In 10 years, at 32, Jonnie Jonckowski would be a world champion bull rider. She won her first World Championship in the now-defunct PWRA (Professional Women’s Rodeo Association) by taking her last ride with a crushed leg after being stepped on in the final round leading into the championship. Her damaged leg had blown up like Popeye’s arm. Doctors warned that a blood clot from the injury could kill her. She didn’t need a high score, just one successful ride to win the championship. Jonnie made it to the bucking chutes on crutches and had to be hoisted onto the final bull. She rode him.

She had her gold medal.

Jonckowski would fly to New York to sit with David Letterman, who commented, “You thought track was too dangerous, so you tried something safer … like bull riding.”

Wisdom, Montana, in Big Hole Basin.

It was maybe my fifth or sixth bronc ride ever. I was in my 20s, and I placed. I got bucked off and broke a couple of ribs, but I was excited. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

Earning that buckle the hard way, fair and square, allowed for such good-natured joking. She didn’t want to be a martyr, or recklessly stupid, just recognized as the world’s best. Jonnie wore the buckle upside down so she could look down and see W O R L D C H A M P I O N. Before then, though, those believing they were protecting a misguided girl way out of her lane had come swooping in without the cheeky humor of Letterman. Everyone seemed to have a righteous opinion, self-assuredly opposed to a naïve girl exhibiting her free will while planning her own funeral.

Others got a charge from helping the curly haired young lady with the big smile, easy laugh, and outlandish plans. After seeing that rodeo poster, Jonnie went to a local bar and found an experienced cowboy to teach her riding basics.

“I was so naïve, I didn’t even know to be afraid,” she said. “If others could do it and survive, how bad could it be?”

She started getting on bulls — with only one hand in the bull rope, not the two hands other women were told to use. She lost count of the times she heard that girls shouldn’t be riding bulls because strong, able men have been killed doing so.

The loudest voice, the one that rang through her head the most, came from her own father.

“My journey as a bull rider was so painful, physically and mentally, especially in a family who didn’t understand it at all,” she remembered four decades later.

The Jonckowski family lived in Montana, but Jonnie, who had two older brothers, was more a city girl. Billings may not have been New York or Chicago with rows of office towers scraping the sky, but Jonnie wasn’t on a farm getting on sheep or going to rodeos like other kids who’d go on to ride bulls.

Her dad, who managed a local Toyota dealership, kept repeating his version of reality: It’s just a phase. A stupid, reckless one. She’ll grow out of it, find something more ladylike to do. Something safe. And proper. And sane. It’s only a matter of time. In time, she’ll get this out of her system.

Only, Jonnie didn’t. The more she tasted the rush of the rides, the hotter the fire burned.

“You don’t do it to get hurt,” she said. “You do it because it feels great when it goes right.”

Her dad would never understand her unquenchable drive or the absolute elation of doing something deemed off-limits for half the people walking planet Earth by virtue of rigid expectations attached to birth chromosomes they didn’t choose. He certainly couldn’t fathom toying with the lopsided

risk-reward ratio of a sport like bull riding.

Jonnie’s mom became her quiet supporter, finding marital middle ground to navigate her husband’s immovable displeasure by quietly acknowledging and encouraging her daughter’s beautifully fierce fighting spirit. Even when a show of support went against every protective bone in her body.

“Mom was always there when I flew out for a rodeo, but never when I came back,” Jonckowski said. “She always thought that when I left, it would be the last time she’d see me alive.”

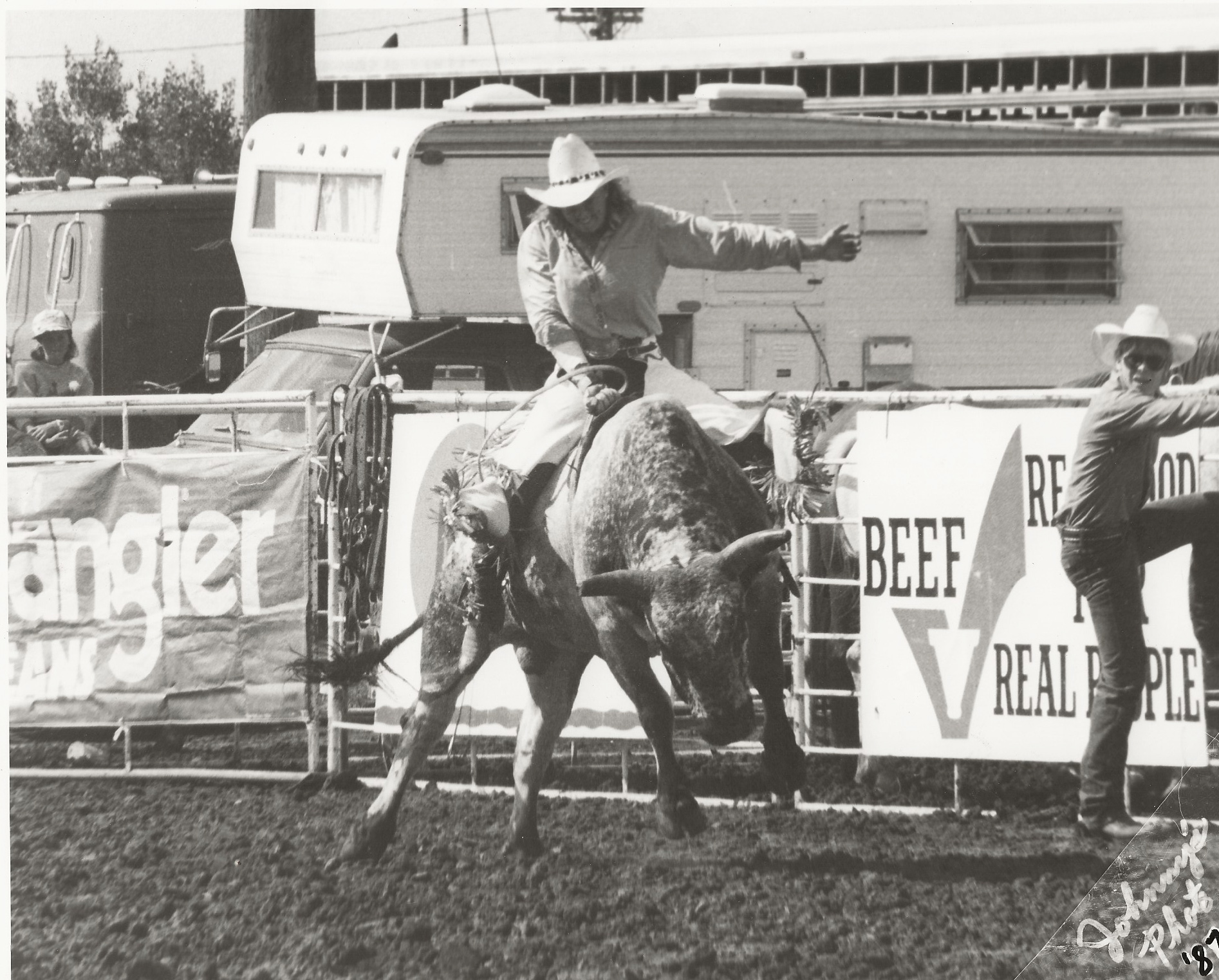

This was our debut after 52 years of the absence of women riding rough stock. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

When she started, Jonckowski had heard bull riding was dangerous but knew little else about the sport.

“At first, I had no equipment and had to borrow a rope and spurs. I didn’t know I had to say ‘go’ and nod my head to get out of the chutes! I’m in there on my bull, and the gate guys were all looking around asking, ‘Is she ready? Is the bull ready?’”

Once Jonnie understood the “go” decision was up to the rider, her first out lasted a respectable four seconds.

“That really turned my crank,” she said. “I’d gotten on broncs and rode bareback. This was a whole different thing. Yeah, it was a case of hook, line, and sinker.”

In practical terms, a mother’s fears and a father’s recalcitrance were justified. In Jonnie Jonckowski’s ongoing project cooking up a mean dish of crow to jam into the gaping mouths of each and every singer in the Choir of Negativity, she would nearly lose her life on more than on occasion. The injuries came quickly. When she first began, she just about lost her nose.

Jonnie wouldn’t have been in the position of facial disfiguration if it weren’t for her plucky stubbornness. She had been rejected for admission to dozens of bull riding schools and camps. None would take a girl. Finally, she called one to enter a “Johnny.” They had no idea Johnny was not a boy. She showed up in Fountain, Colorado, and would train in a school run by Chris LeDoux, a stunning multihyphenate talent who won a bareback world championship and sold more than 6 million records singing country music; former saddle bronc world champion Bobby Berger; and rodeo world champion Bruce Ford.

The quality of the school’s motley assortment of bulls was all over the map. There were some jumpers and a few tough spinners. There were bulls who lunged wildly without rhyme or reason. And so, the student body was dwindling. Guys were dropping out by the day, some out of quaking fear in being fated to an unpredictable bull, others frustrated when quickly eating dirt every time out. The one girl standing tall was a strong-minded athlete with something to prove.

Miles City Bucking Horse Sale in Miles City, Montana, 1981.

Miles City Bucking Horse Sale in Miles City, Montana, 1981.

I was competing in the women's bronc riding and won. I entered the men's and won the men's. We jackpotted the slack and got on 19 horses that afternoon. It was the beginning of a really, really long day. But it was fun. At the end of it, I got handed two buckles and a bunch of money. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

But girl, boy, it didn’t matter. Nobody was going to outmuscle these bulls. The game was one of anticipation, balance, and finesse. Staying on actually came pretty easy to Jonnie even as attendance at the school, which began with more than 100 would-be rodeo stars, was shrinking fast.

On the final day, down to 10 riders, a school champion would be determined. She drew a bull named Spotted Dog. Jonnie made the ride, and when she pulled the tail of her rope to dismount, the bull tripped. She was ready to throw a leg over him, but Spotted Dog hooked a horn and flipped. She was half sitting on the ground and saw a hoof coming at her.

“I thought, Oh God, he’s going to kick me in the face! My head snapped back. I didn’t feel a thing. I thought he missed me. I jumped to the side but couldn’t see well. Bobby Berger and Bruce Ford ran out and said, ‘Jeez, your nose is torn off!’”

Then LeDoux ran out and said, “That you did. But you stayed on. You won!”

Her face looked like it had come out of a blender. Medics applied compresses and loaded her into the ambulance. The motor turned and turned, producing a depressing sound of scraping metal — a dead battery. They climbed into the second ambulance, sinking to one side. Flat tire. Finally, Jonnie was rushed to the nearest hospital — 40 minutes away. Her rotten luck since being matched with Spotted Dog took a humongous, beautiful, life-altering, face-saving turn. A national plastic surgeon’s convention was in town.

The out-of-town specialists who were summoned were excited to see her, she remembers. “A bull had exploded my face apart. I was ripped from my hairline down through my eyebrows across the bridge of my nose. I was a good project for them … like a Humpty Dumpty test dummy.”

Jonnie’s rearranged face was fixed by the very best in the business. At no charge.

Because she stayed on Spotted Dog until the whistle and got a good score, she was school champion, even though nobody would officially admit that. She had nearly lost her face, but they couldn’t lose face by giving the buckle to a girl.

The injury was actually freeing. She’d get back to riding bulls as soon as she could. “My rationalization was ‘I’m too ugly to do anything else; I gotta go back!’” she said. “Besides, God wouldn’t have healed me up so fast if he didn’t want me to go out and do it again.”

She knew she couldn’t control a 1-ton animal, but she could build her gangly body to increase the odds for being in a better position next time. She would virtually live in a gym and get ripped, soon boasting 7 percent body fat.

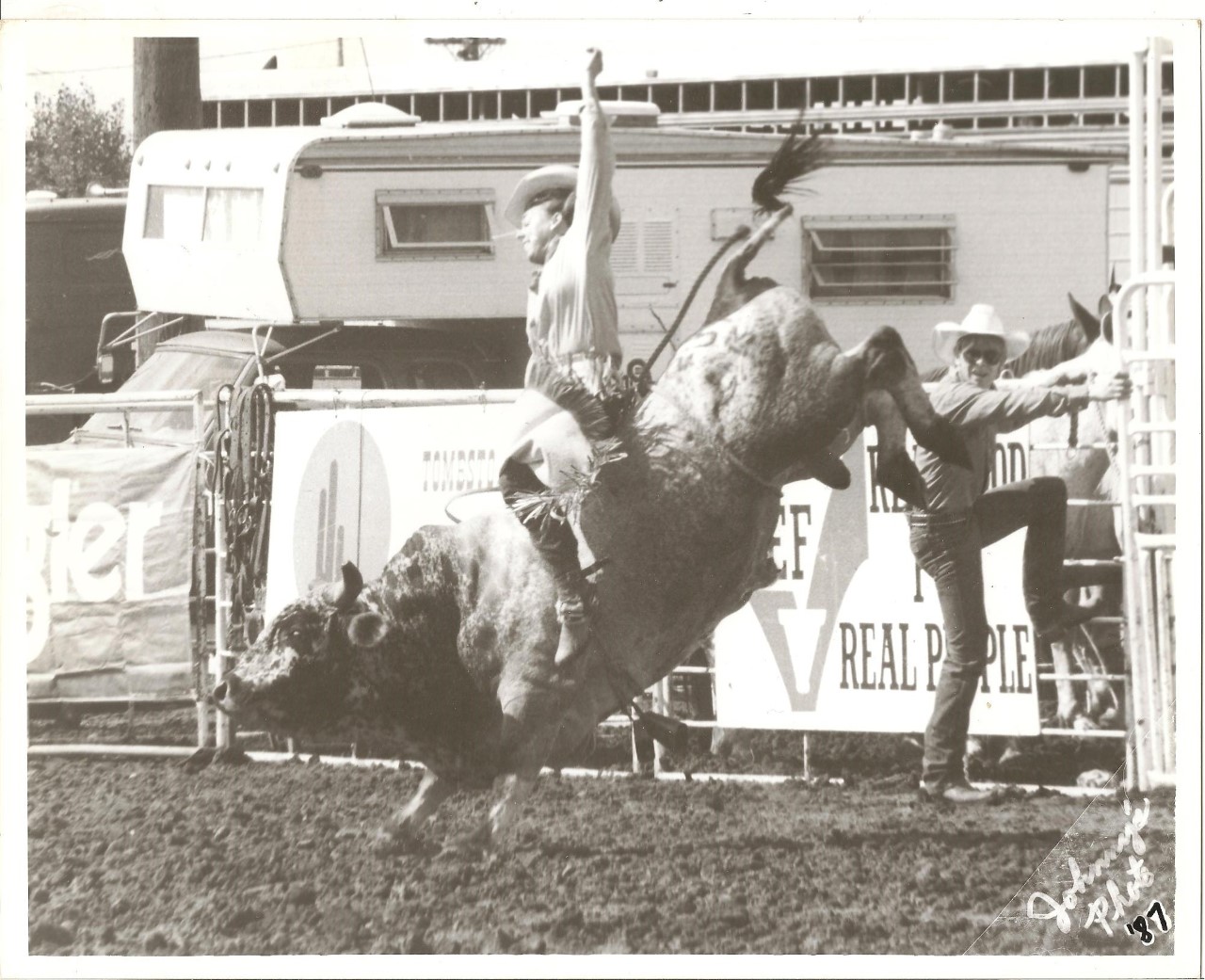

That's me and Mr. T, farther into ride. Notice no vests, no helmets. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

“You gotta be strong through the middle to ride bulls, and my abs were ridiculous. I was a tough son of a gun. A big part of bull riding is reflexes to counteract the bull. As an athlete, I knew that reflex doesn’t go through fat well. Other girls riding were flapping all over the place. I was in control, so I’d get the points."

Jonckowski also knew when and how to play off being a woman. She’d show up at the cowboy’s locker room — and there was only one — in a dress and heels wearing red nail polish.

“I didn’t want them to think I was macho. I was all woman and didn’t want any mistakes to be made by anyone,” she said.

No errors would be made. As the other riders were getting ready, Jonnie would morph from stunning siren to cowboy-athlete stud mode unlike anything they’d seen.

“The other guys were stripping down to the buff, so I’d strip down to my panties and a sports bra to scare the sh-t out of them! And then I put on my riding gear,” she said.

The transformation jacked her confidence and brought results in a sport said to be at least 90 percent mental. One bull, Mr. T, had not been ridden in 42 outs by the best riders in the world. Jonnie rode Mr. T in South Dakota, helping win more respect of riders seeing her earning her stripes, sometimes literally . . . like breaking 12 bones in her arm or getting hit so hard in the back of her head it broke bones in her face, giving her kaleidoscopic vision for months.

“At first it was like a high school dance. I was on one side of the arena, and they were on the other side. They wouldn’t touch me with a stick. But that changed fast. I’d been up and down the road living in a pickup, sleeping in a room with 20 other people. The guys knew I’d paid my dues and earned my stripes.”

Huron, South Dakota, 1987.

Huron, South Dakota, 1987.

The Famous Mr. T! No man had conquered that bull in over a year. I did. The stock contractor wasn't real thrilled, but he was still proud. The crowd got so deafening. The Oak Ridge Boys and Willie Nelson were there. I was supposed to have dinner with Willie Nelson that night. But when that bull bucked me off and I went under him, he stepped so hard on my head that he broke all the orbital bones in my face. Didn't get to go to dinner with Willie Nelson. Two years later, that bull set the highest rider and bull score in Cheyenne history. Mr. T. had quite a reputation. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

Jonckowski deftly courted attention without throwing shade on genuine stars with years of accomplishments like Ty Murray and Tuff Hedeman. Yet she also knew she could cut her own path as a serious draw. She could do the interviews and be gracious to everyone — a happy, humble cowgirl just thrilled to be part of the big show.

“At first, I was living out a small bit of fantasy in my life. But I got serious early on and put in the work and knew I could compete,” she said. “I thought as long as I don’t look foolish out there, with my sex appeal, everyone’s gonna know who the hell I am.”

Jonckowski, a two-time World Champion and 1991 inductee into the Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, retired from riding in 2000 at 46 years old.

“I didn’t quit it; it quit me,” she said. “My body couldn’t take it, or I’d still flippin’ be out there.”

At 67, she has a slightly crooked smile and a scar running down her forehead that would have been a lot worse if not for that plastic surgeon confab in town on exactly the right day. For a long time after hanging up her rope, she wondered, What was I thinking? I’d look in the mirror and say to myself ‘What have you done?’”

What she did was inspire everyone with a dream in any area of life while blazing a trail for every young female rider today who is trying to make it to the top in the new modern era of bull riding.

“I didn’t plan on being different,” Jonckowski said. “All I knew my whole life is to be all out. It takes guts to go out there to do what your heart tells you to do at full bore. I was a bull rider, and if you’re not all or nothing, you probably won’t be a very good one.”

She was a very good one. Jonnie Jonckowski. Say her name.

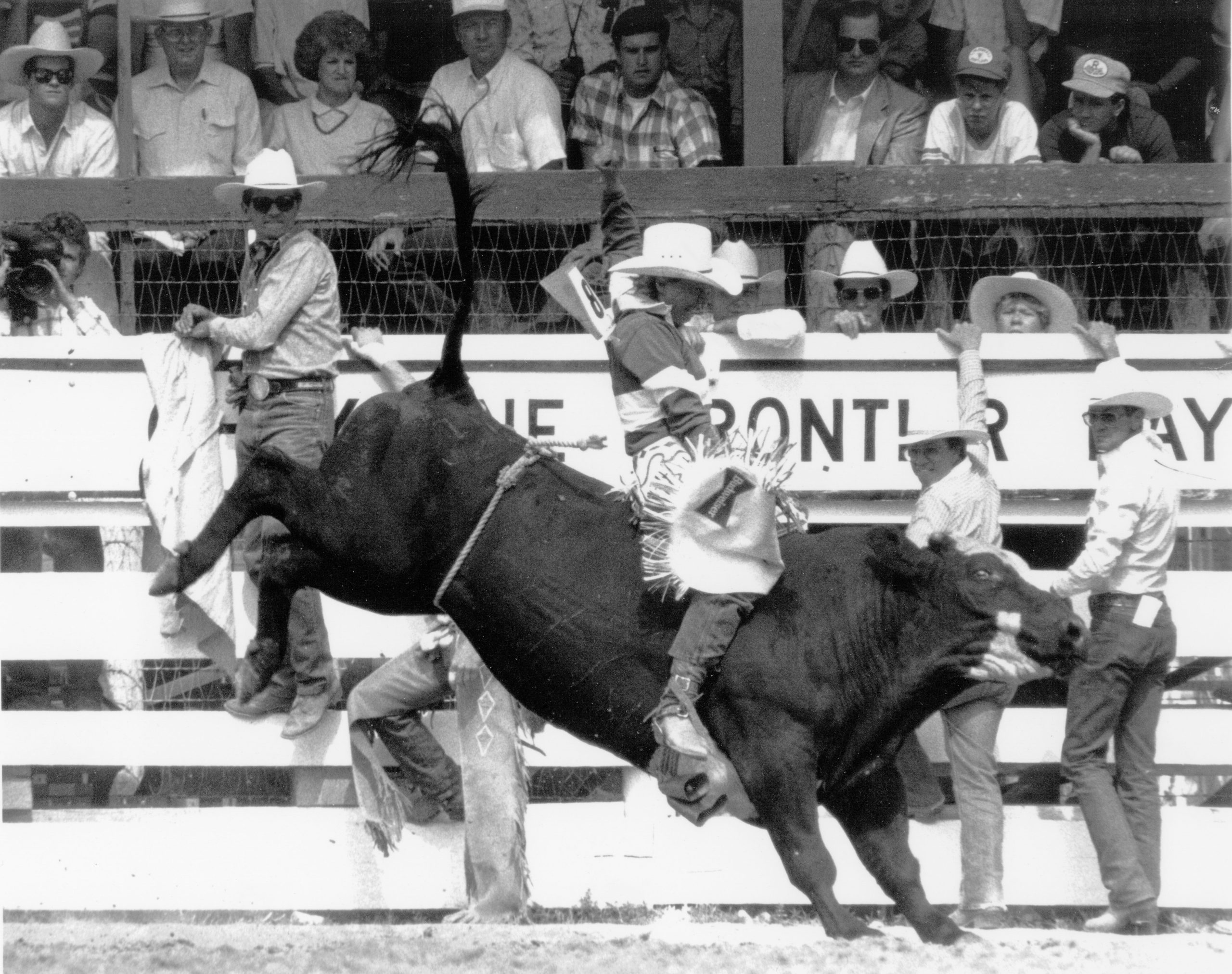

Cheyenne Frontier Days, 1988.

Cheyenne Frontier Days, 1988.

This was by invitation only; there were two women bull riders and two that rode broncs. ~ Jonnie Jonckowski

Excerpted from Love & Try by Andrew Giangola, Cedar Gate Publishing (January 2022). Used by permission.